Jason M. Barr June 17, 2019

Ingrid Gould Ellen is the Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at New York University, and a Faculty Director at the NYU Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. She is the author of Sharing America’s Neighborhoods: The Prospects for Stable Racial Integration and editor of The Dream Revisited: Contemporary Debates About Housing, Segregation and Opportunity.

On Skyscrapers and Housing

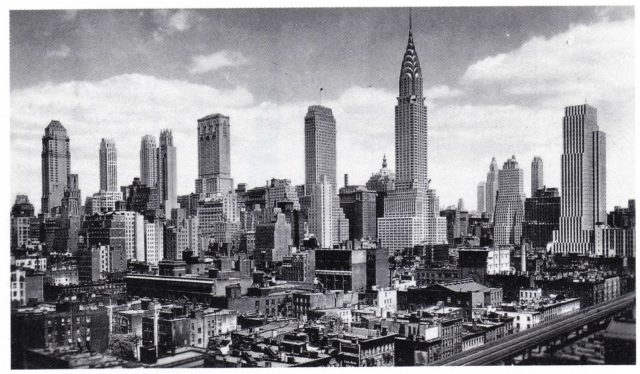

JB: One of the vigorous current debates regarding tall building construction is about luxury residential towers in places like New York, San Francisco, London, and Vancouver. Detractors argue they exacerbate gentrification and income inequality, while harming the quality of street life, and throwing shadows on the street and in parks. What’s your view on the effect of tall luxury residential buildings on cities? Should they be taxed or regulated? Or should they be encouraged?

IGE: The luxury construction boom is a very visible symbol of the inequality that characterizes our nation and our cities. But it is a consequence of inequality not a cause. Rising inequality is helping to drive demand for this type of housing, but that doesn’t mean that limiting construction will do anything to reduce inequality. In fact, local regulations that add cost and risk to permitting and building may exacerbate affordability challenges and only further incentivize developers to build luxury housing. So, it is really important to think rigorously about the potential effects of proposals to regulate the housing market and limit development.

With that said, building more market-rate housing under current conditions will not on its own fully solve the very real affordability challenges in the cities you mentioned, as there is a more fundamental problem that the cost of building and operating decent-quality housing outstrips the ability of many households to pay. If we care about economic diversity in our cities, inclusionary zoning programs that require market-rate developers to build some affordable units or contribute to a housing trust fund can be effective in strong markets in helping to maintain economic diversity and the vitality that it supports.

On Skyscrapers and Street Life

JB: Related to this, when it comes to tall buildings for housing more broadly, there’s a strong belief that they diminish happiness, are bad for vibrant street life, and generate too many negative externalities. In a recent CityLab.com article, Richard Florida, writes:

When buildings become so massive that street life disappears, they can damp down and limit just this sort of interaction, creating the same isolation that is more commonly associated with sprawl. As Jane Jacobs aptly put it: ‘in the absence of a pedestrian scale, density can be big trouble.’ Skyscraper canyons of the sort that are found in many Asian mega-cities, and that are increasingly proposed in great American cities, risk becoming vertical suburbs, whose residents and occupants are less likely to engage frequently and widely with the hurly-burly of city life.

Would you like to offer your thoughts on this? Are tall buildings for housing antithetical to quality of life and the notion of the “good city”?

IGE: Jane Jacobs got a lot of things right when it comes to cities, and I fully agree that “in the absence of a pedestrian scale, density can be big trouble.” But I don’t think that tall buildings are antithetical to a pedestrian scale. Tall buildings can be designed with attention and sensitivity to the pedestrians, with engaging street-level facades that house retail and other inviting uses.

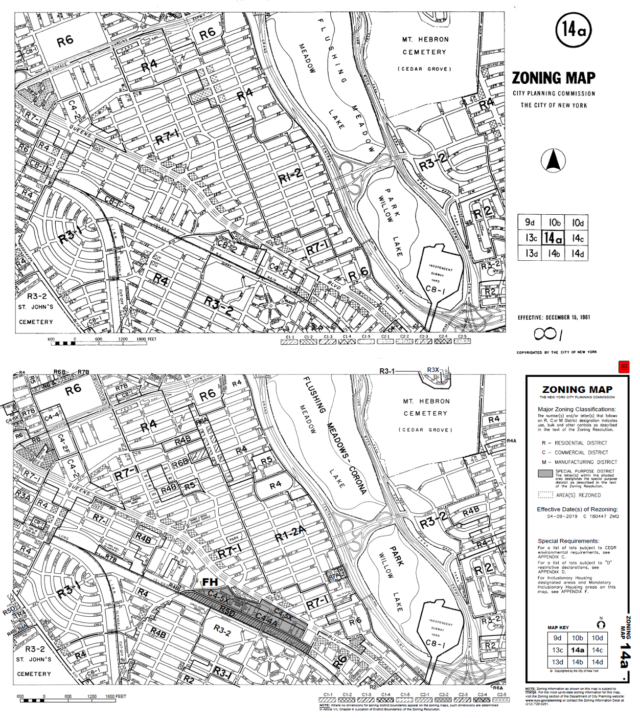

Further, we have to consider the counterfactual. In high-demand areas, the choice is to build up or to build out. Building up helps to create high-density, walkable neighborhoods that are amenable to public transit. Building out creates low-density, automobile-dependent areas, which are clearly antithetical to street life. It’s possible that buildings might get so tall that costs outweigh benefits; but given the zoning restrictions that govern building in cities around the U.S. and many cities in the world, I think we are far away from that point.

On Gentrification

JB: Gentrification in the 21st century is a hot-button issue. The conventional wisdom is that it causes widespread displacement of low-income residents. And cities like Newark, New Jersey, are now actively seeking to prevent it. Based on your research, what are your thoughts on the impacts of gentrification in cities like New York and San Francisco? Do you see, on net, more harm than good coming from gentrification, or the other way around, and if so, why?

IGE: Gentrification is a complicated process, with many potential effects. Most of the discussion around gentrification focuses on direct displacement of existing residents and low-income renters in particular. Yet most of the research that has been conducted on gentrification (including work I’ve done recently in New York City) finds little evidence that low-income renters are more likely to be displaced in gentrifying neighborhoods. To be clear, this research doesn’t say that no tenants are displaced; rather it suggests that turnover rates for low-income renters are no higher in gentrifying neighborhoods than they are in other poor neighborhoods. Low-income renters are unfortunately at risk of displacement in all types of neighborhoods. It’s also true that gentrification tends to come with rising rents, which make it more difficult for new low-income households to move into a neighborhood over time.

While few acknowledge any good that comes from gentrification, we might see a glimmer of hope if we look at gentrification through the lens of integration. The moves that higher-income, white households make into predominantly minority, lower-income neighborhoods are moves that help to integrate those neighborhoods, at least in the near-term. The key is whether this integration will last, and what policies can help to sustain it.

On Gentrification Policies

JB: If you were advising a mayor who was worried about gentrification, what policies would you suggest? What might be the best way to help people who are negatively or unfairly impacted by neighborhood changes due to gentrification? Would you tell the Mayor of Newark that his fears about Newark turning into the next Brooklyn are warranted?

IGE: Most policy discussions surrounding gentrification center on efforts to protect individual residents at risk of displacement through legal representation or tenant-based vouchers. Policies to protect existing tenants from harassment and unjust evictions are critical. But if the mayor cares about diversity and integration, I would also encourage her to consider policies that keep neighborhoods open to a diversity of in-movers, since it is the people moving into a neighborhood who ultimately drive neighborhood composition. For example, creating and preserving place-based, subsidized housing in gentrifying neighborhoods can help to lock in diversity over the longer term and help to affirmatively further fair housing. While New York City may be an outlier, more than 10 percent of housing units in most gentrifying areas of the city are public housing units, and a significant share are subsidized through other programs. If preserved over time, these units can assure some level of economic mixing, and potentially racial mixing too.

It’s also worth noting that while gentrification is a real phenomenon in many cities, far more households around the country live in neighborhoods with persistent poverty. Mayors should not ignore the challenges faced by these neighborhoods and their residents.

On Homelessness

JB: Large cities in the U.S. are also seeing terrible increases in homelessness. Based on your research, what has been the driving factors behind this?

IGE: I’ve learned most of what I know about research on homelessness from Brendan O’Flaherty, of Columbia University. His excellent book, Making Room, argues that homelessness is caused in part by growing income polarization and the disappearance of the middle class. Specifically, the reduction in the number of middle-income households has meant less housing built for them that can filter down to the poor. This has also meant higher rents for the little low-quality housing that is available.

More recently, he has published a very useful review paper in the Journal of Housing Economics. While he highlights a lot of advances in our understanding, he also argues that we really don’t understand why New York and Los Angeles have seen such large increases in homelessness in the past decade, at a time when homelessness across the country appears to have declined. In general, weather, high housing costs and poor labor markets contribute to homelessness, but they do not explain all of the variation.

On Reducing Homelessness

JB: Relatedly, what kinds of policies should mayors and governors be implementing to reduce the homeless population?

That requires a very long answer! But let me focus on prevention policies, which have been found to be promising if they are well-targeted. Studies of New York City’s Homebase program have found that it successfully reduces entries to shelter. The challenge is identifying the households most at risk of homelessness. Many of the families who seek assistance from Homebase would not become homeless in the absence of assistance. There is considerable randomness in which poor families actually become homeless, but individuals likely have some private information about their risk. Prevention programs should figure out creative ways to elicit this information and thus target their services more effectively.

You asked about what mayors and governors can do, but there’s a lot that the federal government can do too. Currently, only one in four income-eligible households in the country receives federal rental subsidies, which significantly reduce the risk of homelessness.

Keep Reading: Part II of this Q&A Interview with Ingrid Gould Ellen can be read here.