Jason M. Barr May 21, 2024

Note: On May 14, my book Cities in the Sky: The Quest for the World’s Tallest Skyscrapers was published by Scribner Books. This post summarizes some of the myths and misconceptions described in the book. For more information, to buy a copy, or to sign up for my email list, please click here.

Because skyscrapers are so big—and tall—they are shrouded in myth, mystery, and controversy. It’s easy to make up stories about them because there’s often little direct information. Developers are naturally a secretive group, and it’s impossible to know how a building has been engineered since it’s covered in glass and stone. And when we look around, we see tall buildings sprouting up while urban life gets more expensive, so it feels correct to conclude that tall buildings are causing the problem.

However, for nearly twenty years, I have been researching the history and economics of tall buildings. Along the way, I’ve heard many of the stories and claims, and have investigated their veracity as much as possible.

Let’s turn to busting some of the myths, starting with the history first and then moving to the present day.

Myth #1: The Home Insurance Building was the first skyscraper, and William Le Baron Jenney was its inventor

Let’s begin with the concept of the “first skyscraper.” The truth is that it’s impossible to name such a thing. The array of elements required to erect tall buildings evolved in fits and starts over the 19th century. This evolutionary process began with structures with external, load-bearing masonry walls with wood or brick internal framing and “ended” with the fireproofed, wind-braced steel skeleton with an electric elevator.

There was never any one technology in the building process that, when incorporated into a building, was so radical that building forms were inherently different after that.[1] It’s also important to note that nobody was trying to invent the skyscraper per se. Architects, engineers, developers, contractors, and suppliers were all trying to figure out how to improve building forms to make them more functional and profitable and to accommodate more people. The idea that someone should get credit for inventing the skyscraper emerged after 1890, when tall buildings rose high across American cities, and people were curious to know how these giants came about.

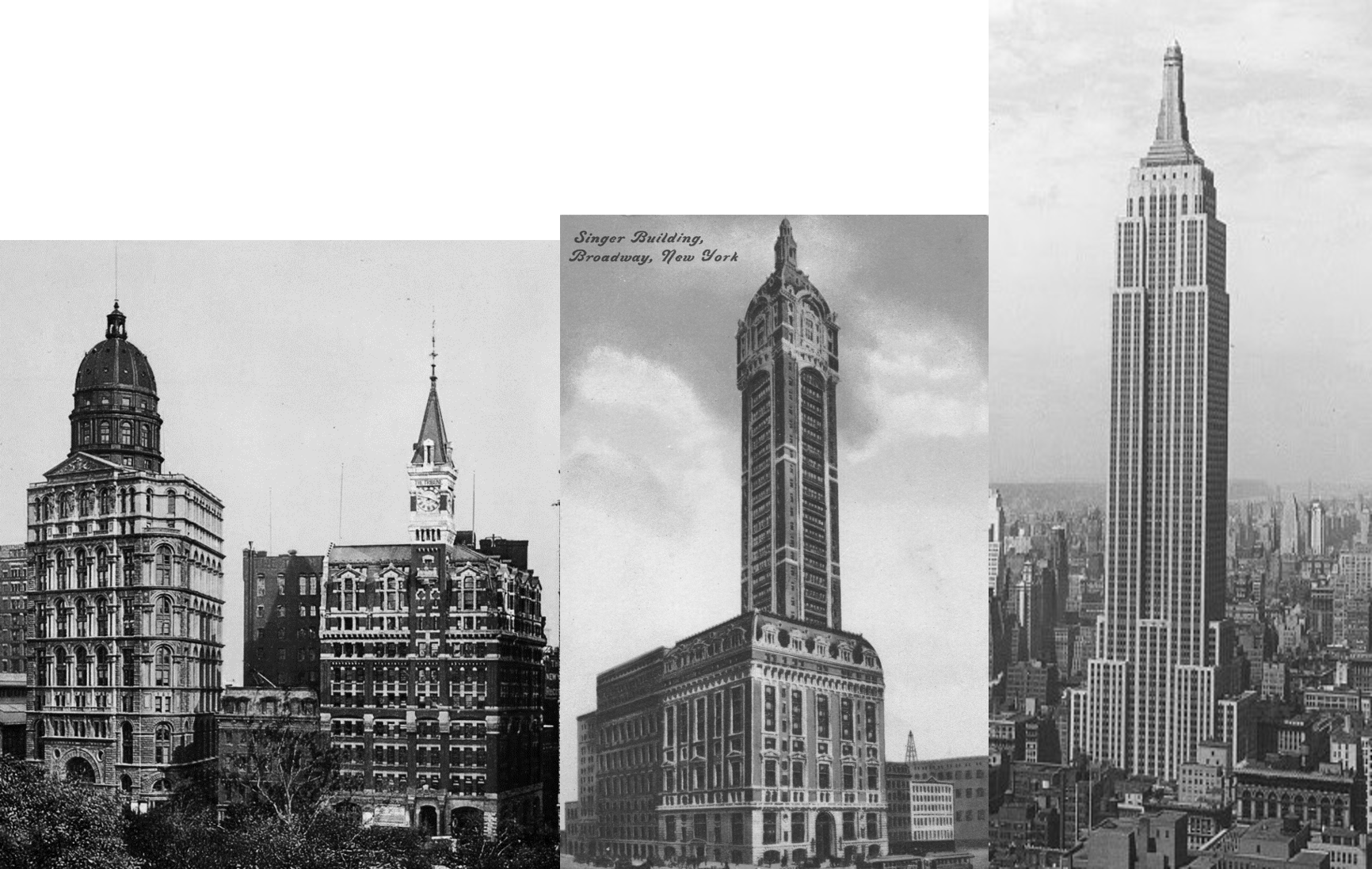

The Home Insurance Building

In 1883, the Home Insurance Company of New York hired the architect William Le Baron Jenney to design a Chicago headquarters. One of Jenney’s engineering strategies was to embed iron columns and beams into the exterior masonry walls to make them thinner to allow for larger windows. Like the countless buildings before him, the Home Insurance Building was an evolutionary step forward.

But a decade later, many architects and engineers claimed they had invented the skyscraper. One was a particularly litigious architect from Minneapolis named Leroy Buffington, who received a patent for iron framing for tall buildings. Starting in 1896, Jenney and his colleagues engaged in a concerted public relations campaign to convince the world that Jenney invented the skyscraper to quash Buffington’s claims. Because the Chicago School architects and engineers were so respected, the world came to believe them, and the notion stuck. Today it is the conventional wisdom that Jenney invented the steel-framed skyscraper. But this idea is a pure myth–a made-up story designed to make a mortal into skyscraper Prometheus. The truth is more mundane: he was clever but hardly radical.

Myth #2: The depth to the bedrock caused skyscrapers to be “missing” in parts of Manhattan

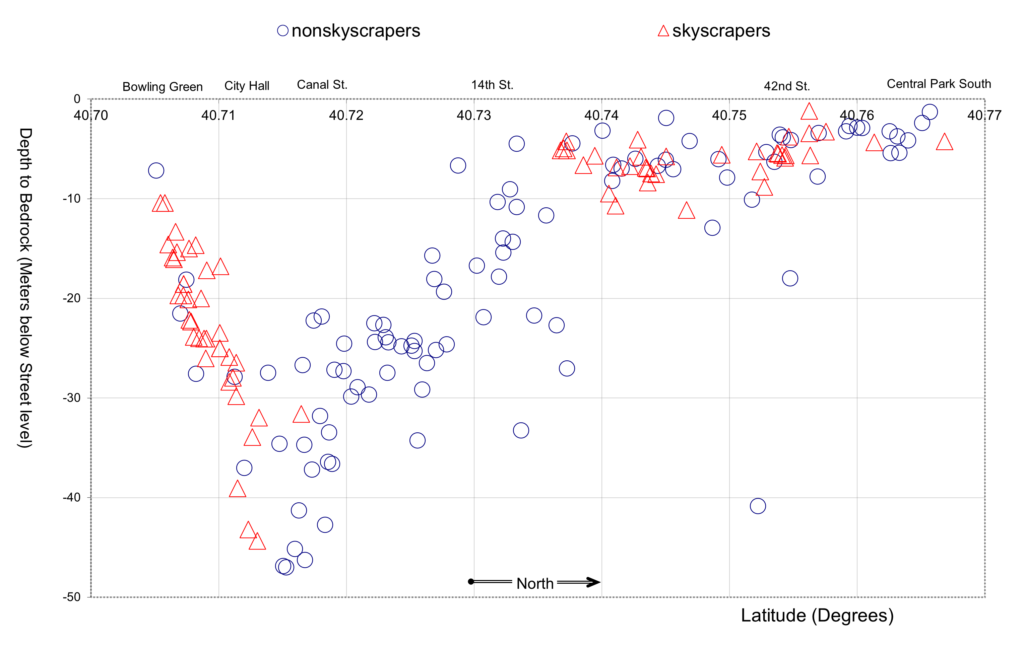

Ask any tour guide or New Yorker interested in Manhattan’s architectural history, and they will tell you that there are no skyscrapers between Downtown and Midtown because the bedrock there was too far down below the surface for developers to anchor their building foundations. Yes, the bedrock north of Downtown is indeed deep below the surface, but it’s wrong that the depths stopped skyscraper construction there. This idea of “missing” skyscrapers was promulgated by a geologist in 1968 because he confused correlation with causation.

The actual reason was demand. At the turn of the 20th century, there was no demand for tall buildings in the tenement and factory districts north of City Hall, precisely where the bedrock was the deepest. If there were, the engineers of the day had the skills and knowledge to make foundations there, but developers didn’t require their services because they couldn’t make money from tall buildings in these neighborhoods. In fact, some of the tallest buildings in the city, like the Woolworth Tower, were built over some of the deepest bedrock spots on Manhattan, so developers and engineers knew what they were doing.

Myth #3: The construction of a record-breaking skyscrapers signals economic doom

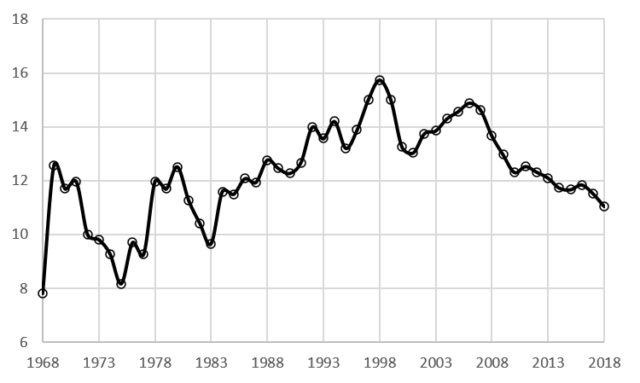

In 1999, an economist named Andrew Lawrence invented the phrase “the skyscraper curse,” which claims that the appearance of a record-breaking building heralds that an economic bubble is about to burst and lead to economic calamity. The idea is that record-breakers only get built during times of irrational exuberance, so we can use tall buildings as an exuberance indicator. Lawrence created the so-called Skyscraper Index which “pairs” tall buildings with crises to “prove” his point.

The only problem is that his logic has many problems. First, the “index” is silent on whether we should be looking at the announcement, groundbreaking, topping out, or official opening of a building. In other words, using tall buildings as an indicator of mania is about as fuzzy a measure as one gets, particularly given the long lags between conception and completion.

But just as important, no matter which version of the indicator you use, there is no way to predict when a crisis will emerge from the completion of a tall building. When one drills down into the data, one finds that there is actually no meaningful connection between the two.

Instead, the Skyscraper Curse is an example of what I call Rorschach Economics. Financial and economic crises have happened twice the frequency compared to the construction of a record-breaking building, so it’s easy to pair a building with a nearby crisis and falsely conclude there is a connection. (It also turns out there’s an “eerie” connection between record-breaking buildings and maritime disasters.)

Myth #4: Record-breakers don’t pay

When the Empire State Building was completed in 1931, its upper half went unrented because of the Great Depression. The building earned the moniker the “Empty State Building,” which led to the myth that record-breaking structures are simply monuments to the ego-driven developer who wants to claim the prize of the “tallest building,” and the economics be damned.

However, to blame the developers for failing to see the arrival of the Great Depression is moving the goalpost. The Great Depression was utterly unforecastable, and its length and severity could never have been foreseen by any developer, no matter how rational. It’s akin to telling a developer in the fall of 2019 to hold off on a new project because a horrible pandemic is coming next spring. No one saw either one coming.

More broadly, the idea that record-breakers don’t pay is a myth. Part of it stems from the true notion that as buildings get taller, they get more expensive to build on a per-floor or per-square-foot basis. For example, more elevators and longer cables are needed, and more steel and concrete are required for wind bracing and foundations. So, people look at the additional costs and assume they are making these projects inefficient.

Costs and Benefits

But you can’t ignore the revenue side. To understand if a project is rational or profitable, you need to look at the net income of buildings over time relative to the cost of constructing them. And when you do this, you see that record breakers make much more economic sense than people think. Even the Empire State Building, which got off to a rocky start, has been consistently profitable for most of its 90-year history.

Today, record breakers are built with more than just economics in mind. They are built to boost tourism, increase property values in their neighborhoods, and put a city on the map. And they generally make money from rents. When we expand the definition of the benefits, we see they are rational projects indeed.

Myth #5: Developers are engaging in rampant “vanity height” competition

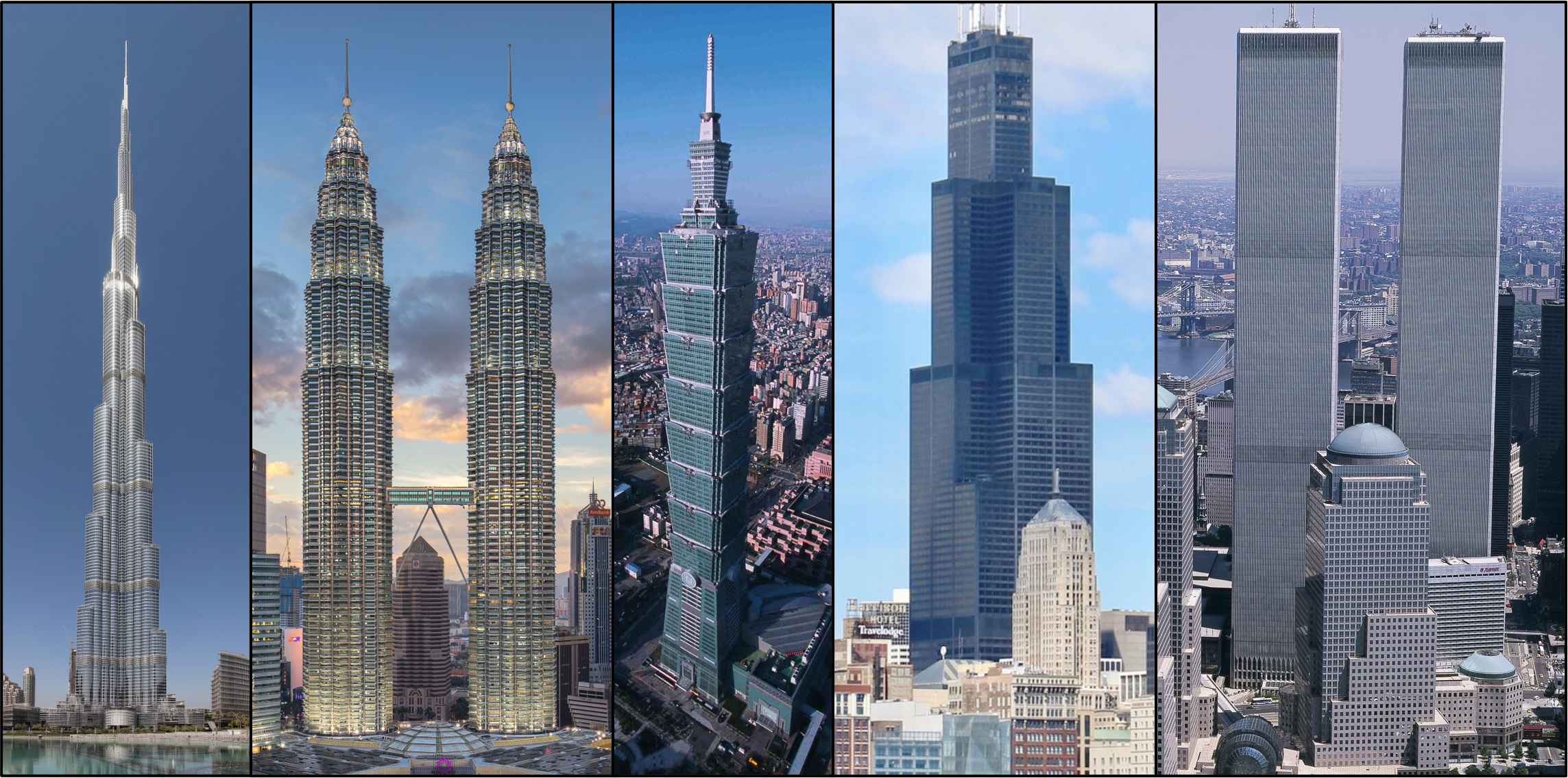

In 1998, when the Petronas Towers were completed and declared “the world’s tallest buildings,” people cried foul. The reason was that it would only be a record-breaker because of the 151-foot-tall (x m) spire. The top floor at 1,230 feet (375 m) was still 124 feet (38 m) below the tallest floor of the Sears (Willis) Tower, completed in 1974.

Until 1998, there were no official measurements, and the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) stepped into this role. As an organization comprised mainly of architects and engineers, they were well-equipped to measure building heights. They determined that if a building had a spire that is architecturally part of the structure, it counts toward the overall height of the building.

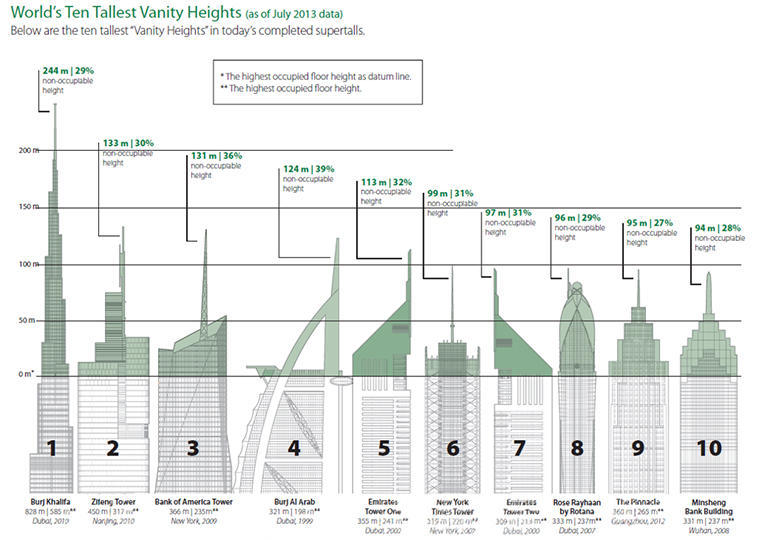

Since then, extruding spires have become a way to raise a building’s “neck” even higher. The next record breaker after the Petronas Towers, Taipei 101, has a spire that is 230 feet (70 m), and the Burj Khalifa’s spire is a whopping 801 feet (244 m).

The Vanity Height Myth

The use of spires to help extrude record-breakers has led to what I call the Vanity Height Myth: that spires are getting taller and are the only way to break a record. However, except for the spires on Petronas Towers, the floor heights of the record breakers are all taller than previous record holders. Just as importantly, spires are essential to the structure’s architecture.

No one complains about the spires on the Empire State or Chrysler Buildings—we celebrate them. Yes, there are some examples of what seems like “let’s put a spire on our building to make it taller”—One World Trade Center comes to mind—but for the most part, spires either add to the elegance of the building or are not needed to be a record breaker. For that matter, the Twin Towers and Sears (Willis) had no spires.

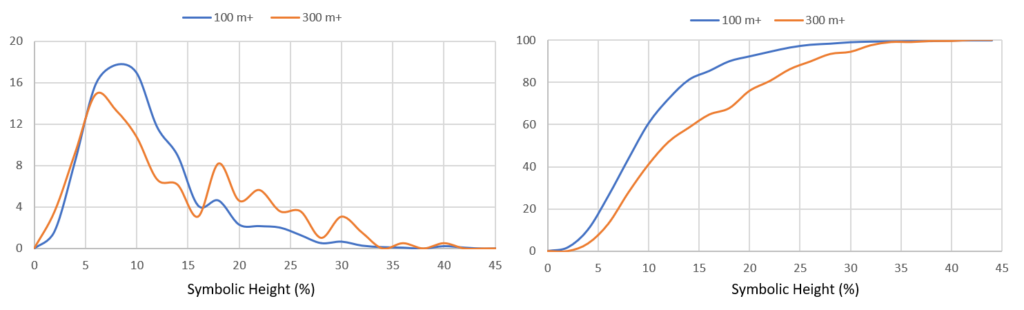

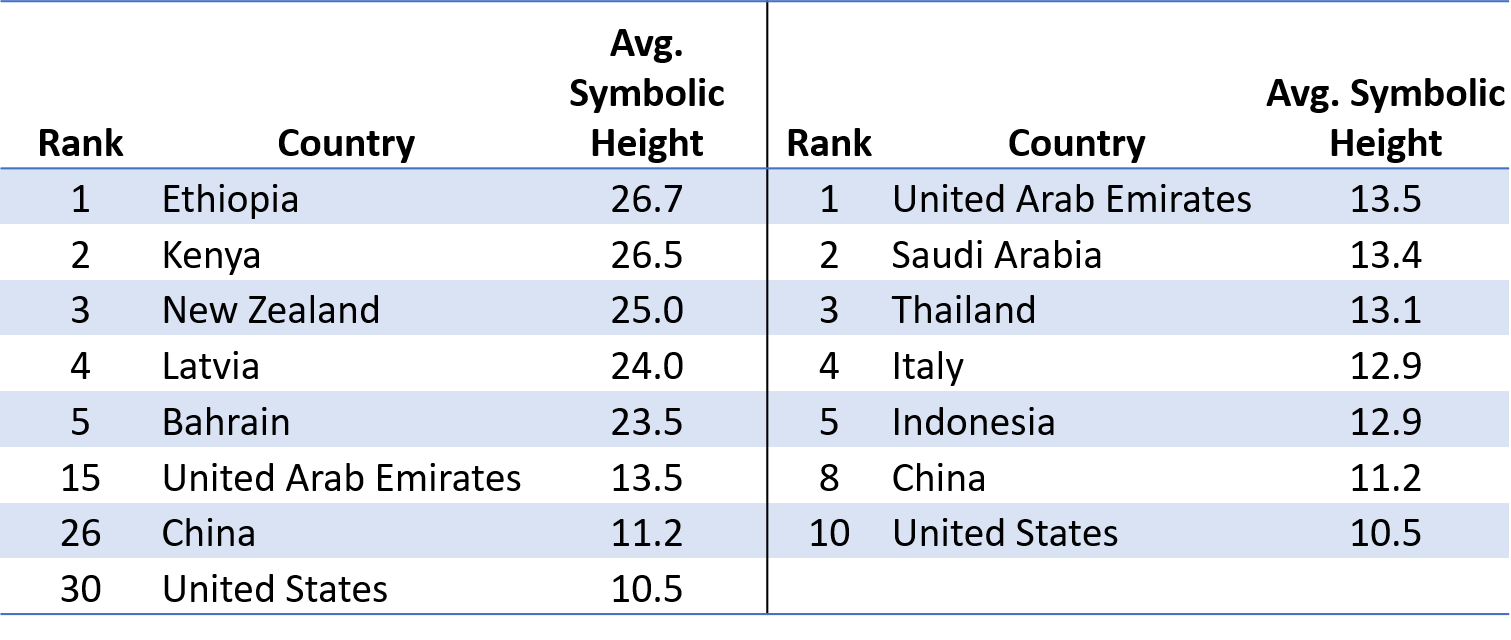

More broadly, I investigated the differences between the architectural height and the top floor height for a sample of nearly 2,000 buildings of 100 meters or taller buildings completed worldwide. My finding is that, on average, the difference represents only 10% of the total structure’s height. For supertall skyscrapers of 300 meters (984 feet) or taller, that average is still relatively low at 12% (median of 9.7%). In short, across the spectrum, vanity height is actually a very small—or short—part of tall building design.

Myth #6: Tall buildings are only for the rich

In global cities like New York and London, the skyscrapers erected in central areas tend to be apartments for the rich or global headquarters for international firms. This phenomenon has led to the idea that tall buildings are only for the wealthy. Yes, tall buildings are more expensive than shorter ones, but nothing is inherent in the structure’s economics that makes them only for the wealthy.

Spend five minutes in any Chinese city to see this. Tall buildings are built for nearly everyone—the homes of the middle class in cities large, medium, and small. Unlike in America, where free-standing, single-family homes are the norm, high-rise apartments are typical in China. The country has been building them in spades, so much so that China is in the midst of a housing crisis, with nationwide vacancy at 15%.

More broadly, when it comes to costs, there is a u-shaped relationship between height and per-square-foot or -meter costs, but the floor count where the lowest point is hit depends on many factors. One study of high-rise housing costs in Hong Kong found that the minimum per square meter cost was 100 meters (about 30 floors or 328 feet), on average. Overall, if planned properly on a large lot, built by an efficient construction sector, and with few stringent building regulations, tall buildings can be built as cost-effectively as low-rise ones.

It’s also worth remembering that American high-rise public housing was a failed policy not because of construction costs. They were built quite cheaply. The problems, in brief, were public policies that hyper-concentrated poverty while housing authorities under-maintained the buildings.

Myth #7: Skyscrapers make cities more unaffordable

Global cities like New York and London are very expensive places in which to live. Most people blame the high-rises. The logic goes that high-rises are costly to build and only for the rich. So, the rich move in, displace the poor and make housing less affordable for everyone.

But this notion confuses causation with correlation. Simply put, big cities are not building enough housing for everyone. New York City has a citywide housing vacancy rate of 1.4%! In London, that vacancy rate is 1.7%. There is no extra housing for anyone.

But it’s easy to focus on tall buildings because they are most likely to be noticed when we observe new construction in the city. In truth, more tall buildings are likely being built than new low-rise buildings because cities, by design, keep most of them closed for new construction and only allow tall buildings in the center, where it’s the least politically costly to do so.

Positive Spillovers

However, tall buildings do have beneficial impacts on the prices of nearby buildings. Two studies, for example, one in America and one in Helsinki, followed people who moved into new centrally located high-rise buildings. They found that the majority originated from their respective metro regions. Then, they tracked those who moved into their “abandoned units” and found that they had, on average, lower incomes. So, in short, building high-rise housing in the center frees up lower-cost housing for those within lower income brackets. Another group of cutting-edge studies has shown that adding new housing supply lowers nearby housing prices. Additionally, a cluster of studies show that reducing zoning stringency leads to more construction and lower housing prices.

But why don’t we see it? The reason is that supply increases are swamped by rising demand and income. Believe me, if citywide housing vacancies—including in the lowest-income neighborhoods—were, say, between 7% and 10%, no one would blame high-rises; instead, they would be saying that they are solving the housing crisis.

Myth #8: Five- to ten-story buildings are the ideal for cities

Tall buildings get a bad rap for all sorts of reasons. They tend to emit more greenhouse gases, and people feel they are alienating and inherently harmful for aesthetically pleasing cities while only being palaces for the rich. On the other hand, urban advocates look at the sprawling suburbs and see excessive car dependence and expensive single-family homes.

Urbanists thus point to Greenwich Village with its five-story walk-ups and Second Empire Paris with its seven– to ten-story mansard-roofed buildings as ideal for creating the “human scale.” These urban areas have given rise to the perception that they have the “perfect” density. They have lower carbon footprints, a high enough density to sustain mixed uses and promote pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods.

It must, therefore follow, the logic goes, that to create the perfect Jane-Jacobs-approved city, we must require all cities to have five- to ten-story apartment buildings everywhere. I love Paris and Greenwich Village as much as the next person, but the only problem with this logic is that imposing height caps or trying to mandate “Goldilocks Density” does more harm than good. By ignoring the economics of land use and people’s wishes, height caps and building type requirements generate a bevy of unintended consequences, including higher housing prices, more carbon emissions, sprawl, and lower employment growth.

In the Center

Skyscrapers rise in the center because more people want to be at these locations than can be accommodated by a low-rise building. In this case, the only way to accommodate this demand is to go up. Farther away, where commuting to the center takes longer, people should have access to low-rise neighborhoods with more space per household. The cost and benefits of being in different locations must drive the housing types.

Policies need to consider this fundamental trade-off: smaller housing units and taller buildings in valuable locations and larger units in low-rise buildings further away. If a city perverts this trade-off, it makes people worse off. A one-size-fits-all policy harms cities and their ability to successfully attract people and provide employment opportunities. The natural way to densify neighborhoods is to provide efficient public transportation, parks, access to retail, and good schools and let the supply match the demand.

Truth #1: We need to think more deeply about cities

The conclusions about tall buildings that people make often arise from the confusion of correlation with causation or by generalizing based on one or a handful of observations. We need to discover the truth by looking deeply at the data, inquiring into how people respond to incentives, and uncovering the logic of social systems. Please join me in this endeavor!

—

[1] If one technology made the biggest difference, it was the elevator, which radically changed the economics of going tall since now occupants would rent the higher floors for more money than the lower ones.