Jason M. Barr July 24, 2023

Author’s Note: This blog post is the second in a series that brings to light Robert Moses’ forgotten role in New York zoning and planning history. Post I from 1938 to 1941 is here.

Robert Moses, the Master Builder of New York City from the 1930s to the 1960s, is famous—or infamous—for the staggering number of projects he built. He started with parks and parkways and expanded to bridges and tunnels, highways, housing projects, and slum clearance.

Lost in all the discussion, however, was that Moses was also a member of the City Planning Commission (CPC) for twenty years. Though this position was less visible than his leadership of the Triborough Bridge Authority or the Parks Department, Moses’ role at the CPC deserves more attention than it has because it has impacted the city, nonetheless.

A Brief History of the CPC

In 1933, Fiorello La Guardia was elected Mayor of New York. He was determined to clean up city government, which for decades has been run by Tammany Hall Democrats. La Guardia brought in Robert Moses as Parks Commissioner, who immediately initiated a vast program of building swimming pools, parks, and parkways.

In 1936, La Guardia spearheaded charter reform to centralize power in the mayor’s office. The new charter created the City Planning Commission. Many people expected that Moses would take the helm, but he refused. He was unsure exactly what the CPC was supposed to do and was not interested in figuring it out.

Instead, in 1938, La Guardia chose as the CPC’s first leader the economist and FDR advisor Rexford Tugwell. Tugwell, a devotee of master planning, arrived with a vision of what the Commission should do. He had three signature items on his agenda. The first was to undo the problem of non-conforming uses. Tugwell wanted urban order and could not stomach things being where they ought not to be. His first major initiative was to ban signs and billboards at locations where they were originally grandfathered in 1916.

Failures

A business and real estate coalition, however, formed to stop him, afraid that the proposal was just the tip of the iceberg toward greater interference in the property market. Ironically, Tugwell received support from Moses. Given his career building parks and parkways, he, too, thought signs and billboards could be a nuisance.

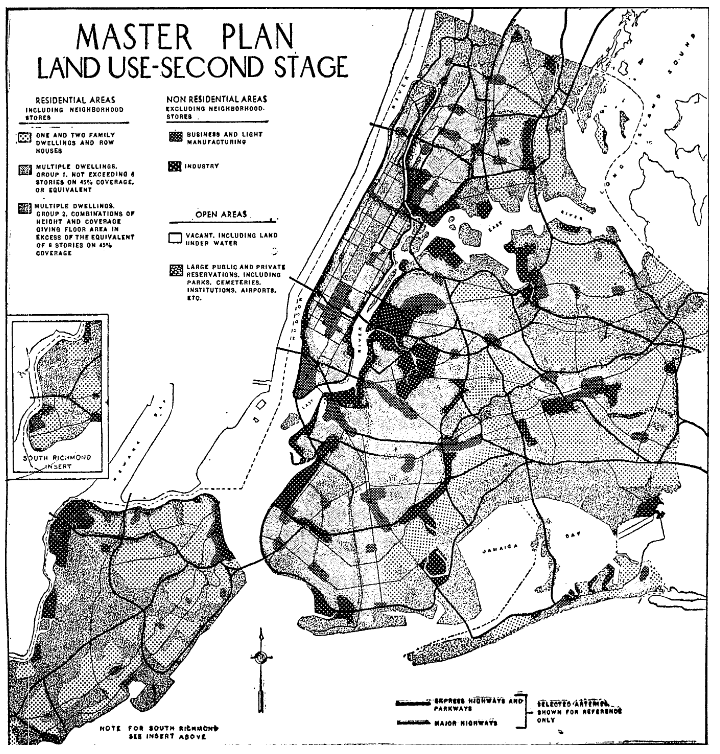

Next was a Master Plan of Land Use, comprised of maps with stricter boundaries for future allowable land uses and a vast greenbelt. New York would become a Garden City, whether it wanted it or not. Here Moses was his foe and helped lead the charge against the plan, as it struck him as too radical.

The third policy was to revise the zoning resolution—particularly by downzoning the city. But Tugwell never got his chance. Instead, he could only pass changes to a few residential districts. In particular, the CPC created several single-family-home-only zones and introduced Floor Area Ratio (FAR) caps in suburban areas. Moses went along with these as he was fine with downzoning in residential neighborhoods.

Moses on the CPC

After the billboards loss, Tugwell’s failure to pass the Master Plan was the last straw. He quit his position in 1941 and soon became Governor of Puerto Rico. La Guardia chose as the new chairman Edwin. A. Salmon, already a member of the CPC. Robert Moses was picked to fill the vacant seat. Almost immediately after taking office, Moses pushed the CPC to formally scrap Tugwell’s Master Plan.

During the three years of working with—and battling against—Tugwell, Moses learned what the CPC could and should do. Furthermore, being on the inside would be useful, aiding him in his other endeavors. As planning historian Stanislaw Makielski writes, “Moses saw city planning as a matter of meeting the city’s needs on a project-by-project basis, and he never gave his full attention to the activities of the Planning Commission, using it chiefly as an additional source of information and as a public forum for his own brand of planning.”

Long Haired Planners

As discussed in an earlier blog post, Moses occupied a position squarely in the political middle. On his left were those he labeled as “long-haired planners” (although, as best I can tell, they all had short hair). In June of 1944, Moses published a screed against them in the New York Times Magazine. In so many words, he told eminent modernist thinkers like Eliel Saarinen, Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Rexford Tugwell, and even Frank Lloyd Wright to shut the f*** up.

Moses was a man who did things like build parks and roads, and their planning theories were poisoning people’s minds, or, as he wrote,

In municipal planning we must decide between the revolution and common sense—between the subsidized lamas in their remote mountain temples and those who must work in the market place. It is a mistake to underestimate the revolutionaries. They do not reach the masses directly, but through familiar subsurface activities. They teach the teachers. They reach people in high places, who in turn influence the press, universities, societies learned and otherwise, radio networks, the stage, the screen, even churches. They make the TNT for those who throw the bombs. They have their own curious lingo and double talk, their cabalistic writings, secret passwords and abracadabras.

Moses also had little patience with the laissez-faire-ists who felt the government had no business telling people what to do with their property. While Moses disdained wholesale reforms, he was a fervent devotee of modernization and “cleaning up” the old metropolis. He believed in slum clearance because the new housing had more open space, was less dense, and was laid out according to proper standards. Like many planners of his day, Moses adhered to the dictate of better living through the tower-in-park.

The Moses Plan of 1944

By the spring of 1944, it was clear that the war would be winding down, and the time was ripe to implement zoning reform ahead of the expected post-War boom. After the Roaring Twenties, there was broad consensus among planners that the 1916 codes were too lenient.

With Tugwell out of the picture, Moses felt it was his turn to take a stab at rezoning. If he could get through a more conservative resolution, he might put the left at bay for a while. Still, Moses firmly believed in the necessity of downzoning. As he wrote to his fellow commissioners in May 1944, when he introduced his new plan:

It is ridiculous to apply high standards to public housing, to redevelopment corporations and to limited-dividend companies, and not apply them to speculative or ordinary private buildings.

All of the buildings, public, semi-public or private, contemplated in the postwar period will accomplish nothing toward improving city life unless the zoning standards are jacked up. At the present time the zoning standards are so low that in a good many cases we are entirely dependent on the Multiple Dwelling Law from relief on over-building….

I should like to go very much beyond these amendments and to make them a good deal more drastic, but it seems the approach should be gradual and conservative. I know of no reason why the rise in standards here proposed should meet with opposition from any reasonable citizen or organization.

Moses’ proposal could be called 1916 2.0. New buildings’ allowable envelopes would be lowered—their street wall would rise to lesser heights, and their setbacks would be more severe. Additionally, the open space requirements around each structure were expanded. The net effect was to reduce a building’s bulk as a function of the then-current rules; each zoning district would thus be dialed down a notch.

Moses Tackles His Opponents

Moses brooked no dissent. He knew he had the other commissioners and La Guardia lined up, and he needed to keep them unified against the opposition. When The Committee on Civic Design and Development, a group formed by the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), for example, wrote a report arguing for more sweeping changes, La Guardia asked for Moses’ opinion. He replied to the mayor, “This report is the work of the same radical group who have always insisted that our planning is not sufficiently revolutionary. You will never get anywhere in trying to argue the matter with them.”

And echoing his run-ins with Tugwell three years early, Moses reminded the Little Flower, “These people want a master plan and zoning system on entirely new constitutional and legal theories.” And relishing the opportunity to trash-talk them down the line, Moses added, “My very earnest advice to you is to ignore this report. I can tell you more about the individual members of the committee if you wish.”

Robert Kohn

Interestingly, Moses received a letter from Robert D. Kohn, who, as I argued in a prior blog post, invented the Floor Area Ratio in 1935. Kohn was a highly respected reformer and architect who served in the Roosevelt administration as the first housing chief of the Public Works Administration (PWA). As Parks Commissioner, Moses managed to commandeer a sizable WPA allotment to build up the city’s park system. It seems reasonable that he would have met Kohn.

Kohn was also a founding member of the influential group the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA). His architect partner, Clarence Stein was also an important reformer and initial RPAA member, and had led the New York State Commission of Housing and Regional Planning in the early 1920s under Al Smith’s administration while Moses was building out Jones Beach.

The letter from Kohn to Moses offered some slight changes to Moses’ plan as it related to large buildings on entire blocks but was supportive of the downzoning plan overall. Moses’ response to his fellow commissioners was to belittle Kohn and accuse him of hypocrisy, telling them,

Attached is a letter from Robert D. Kohn. Mr. Kohn and his partner Stein are advanced thinkers of planning. Both of them are of the school that advocates drastic reorganization and much higher standards until it gets down to anything which affects their immediate prospects of the commission.

To Moses, the phrase “advanced thinkers” was no doubt an insult, as he clearly associated “advanced” with “radical.”

Moses was likely aware of Kohn’s role at the RPAA. He obliquely refers to (and rejects) their position in his report on his plan to the Board of Estimate. Again, Moses tries to outflank those on the left, by signaling to the Board of Estimate what he sees as their radical position:

The Commission is not proposing further restrictions on the height and bulk of buildings out of sympathy with current theories regarding “decentralization” and the scattering of population and activities over larger areas of the countryside. On the contrary, its purpose is to check trends toward “decentralization” which threatens values based on the manifest advantages of centralization and concentration of people and activity in a community such as New York.

Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire

Moses also attacked those on his right. For example, he accused the leader of the real estate interests opposing the new plan, Robert W. Dowling, of being a liar. Moses complained to the other Commissioners that,

I just want to point to one thing as an evidence of the kind of opposition there has been to these proposals; the unscrupulous character of the opposition. One of the things that Mr. Dowling and his publicity man have relied upon has been the statement that reputable fiduciaries, such as banks, particularly, savings banks, and insurance companies, have filed plans for large buildings—that these plans and the buildings projects will be abandoned if the new standards are adopted; and, that, therefore, the new standards are a very wicked thing. They have even had the effrontery to go to labor unions and tell them that the members of the building trades won’t have any work if we carry out this program.

Well, I have a little familiarity over a period of years with the insurance and banking laws—in fact, wrote quite a little bit of the Banking Law. So, I got in touch with the Superintendent of Insurance first in connection with plans for a building filed in the Building Department where he was indicated as the owner. I asked him what authority he had or anyone in the Insurance Department had for filing the plans. Mr. Dineen, the Superintendent, sent me the man who is in charge of liquidation, who admitted that he didn’t have the slightest thought of ever building such a building, that he was simply trying to create a market—the appearance of a boom—so that he could sell the property at a higher price. Mr. Dineen, this morning ordered the plans withdrawn from the Building Department….

That gives you a rough idea of the activity of Mr. Dowling.[1]

The Huie Maneuver

It was one thing for outside groups to criticize Moses, but fellow commissioner Irving Huie had an alternative proposal that Moses did not like. Huie (1897-1957) was born in Brooklyn. He graduated from New York University in 1911 with an engineering degree. After World War I, he served in city and state positions and private practice, helping to build infrastructure, such as highway construction in New York and Pennsylvania. In 1938, he became chief engineer for the city’s newly formed Department of Public Works. When he was appointed to the CPC in 1941, he was seen as an able official and “doer” like Moses.

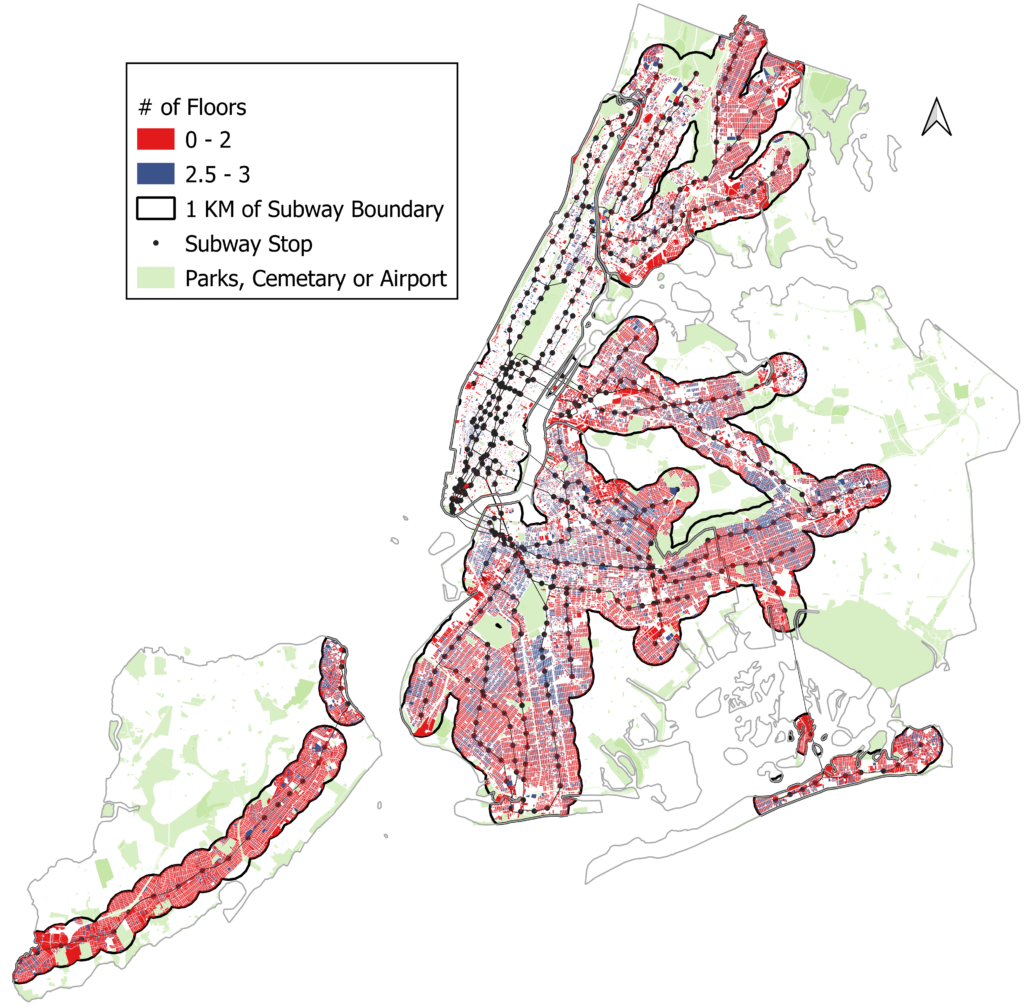

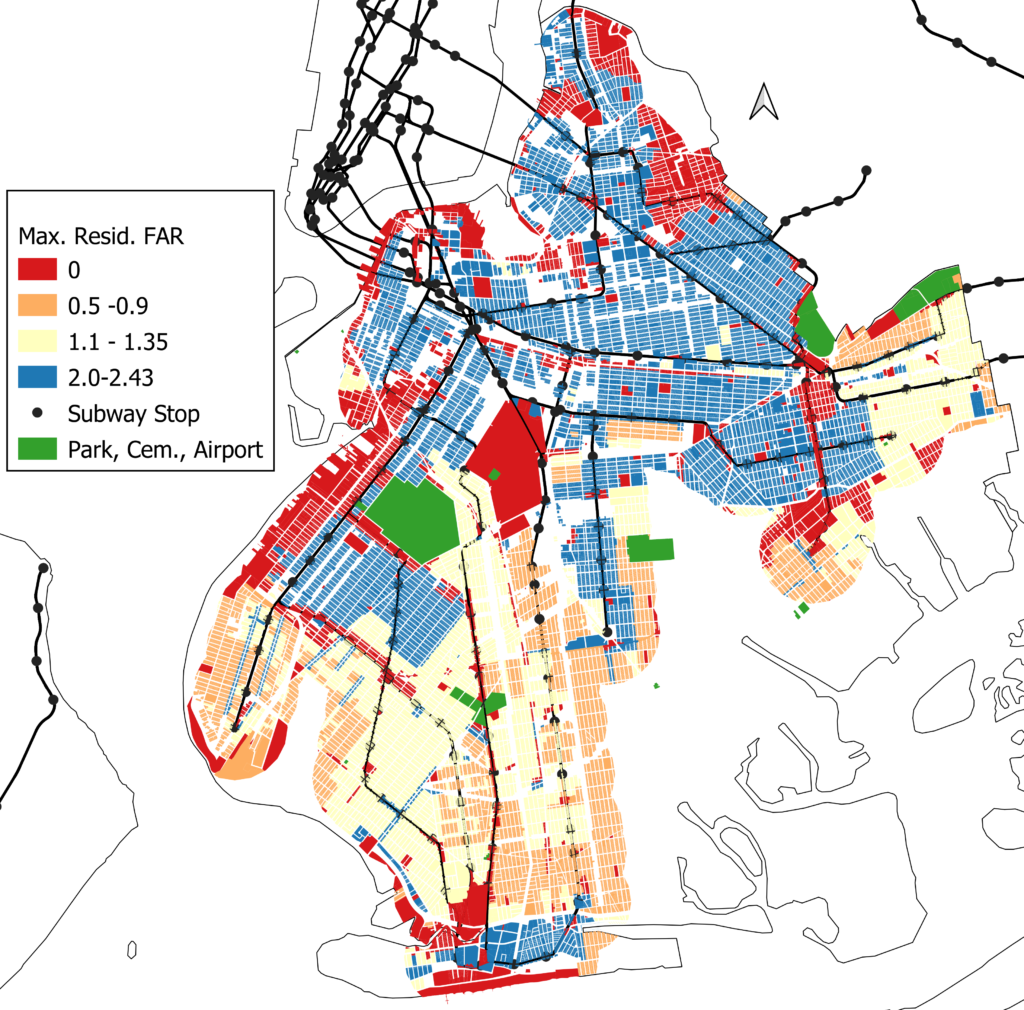

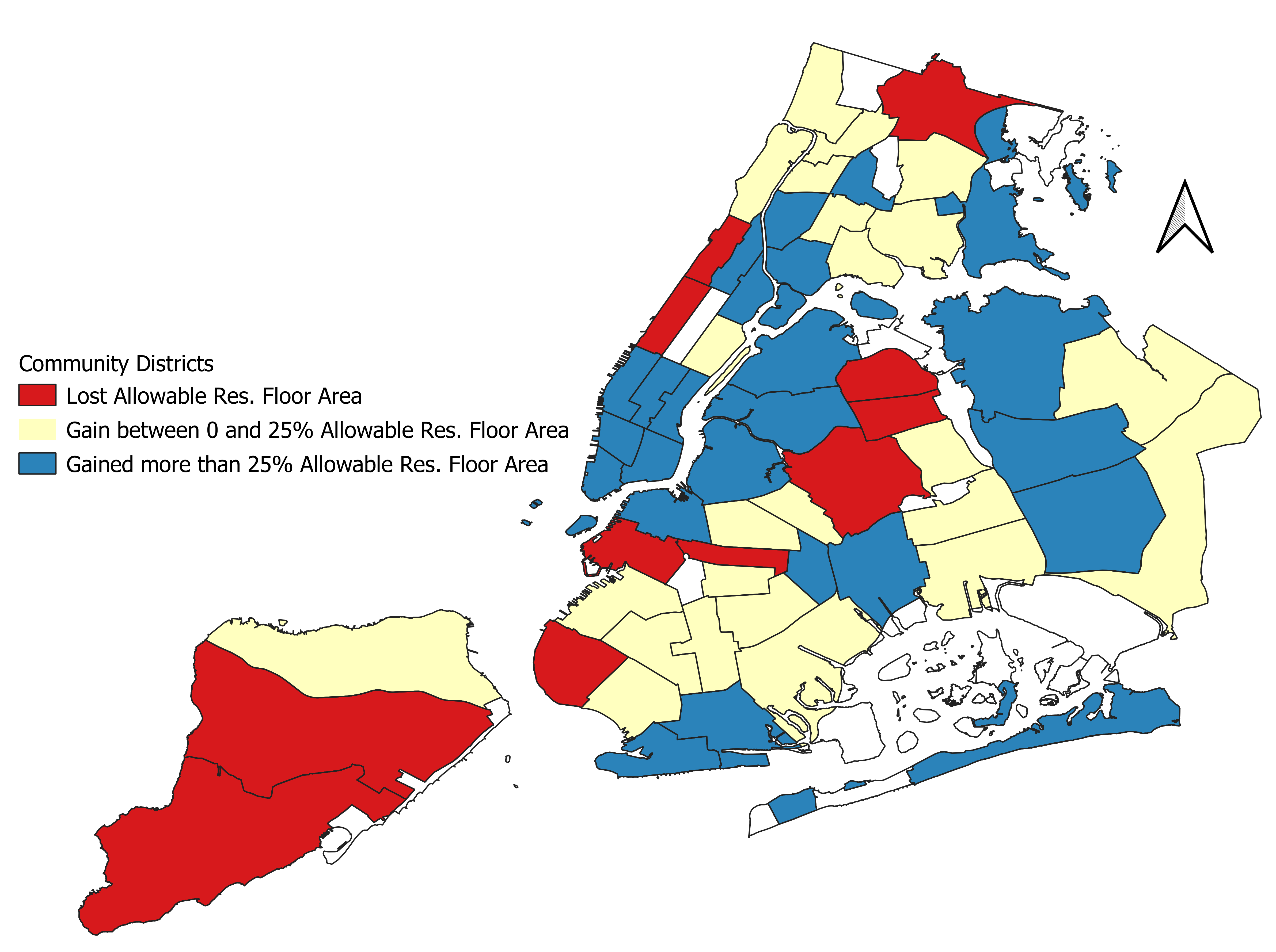

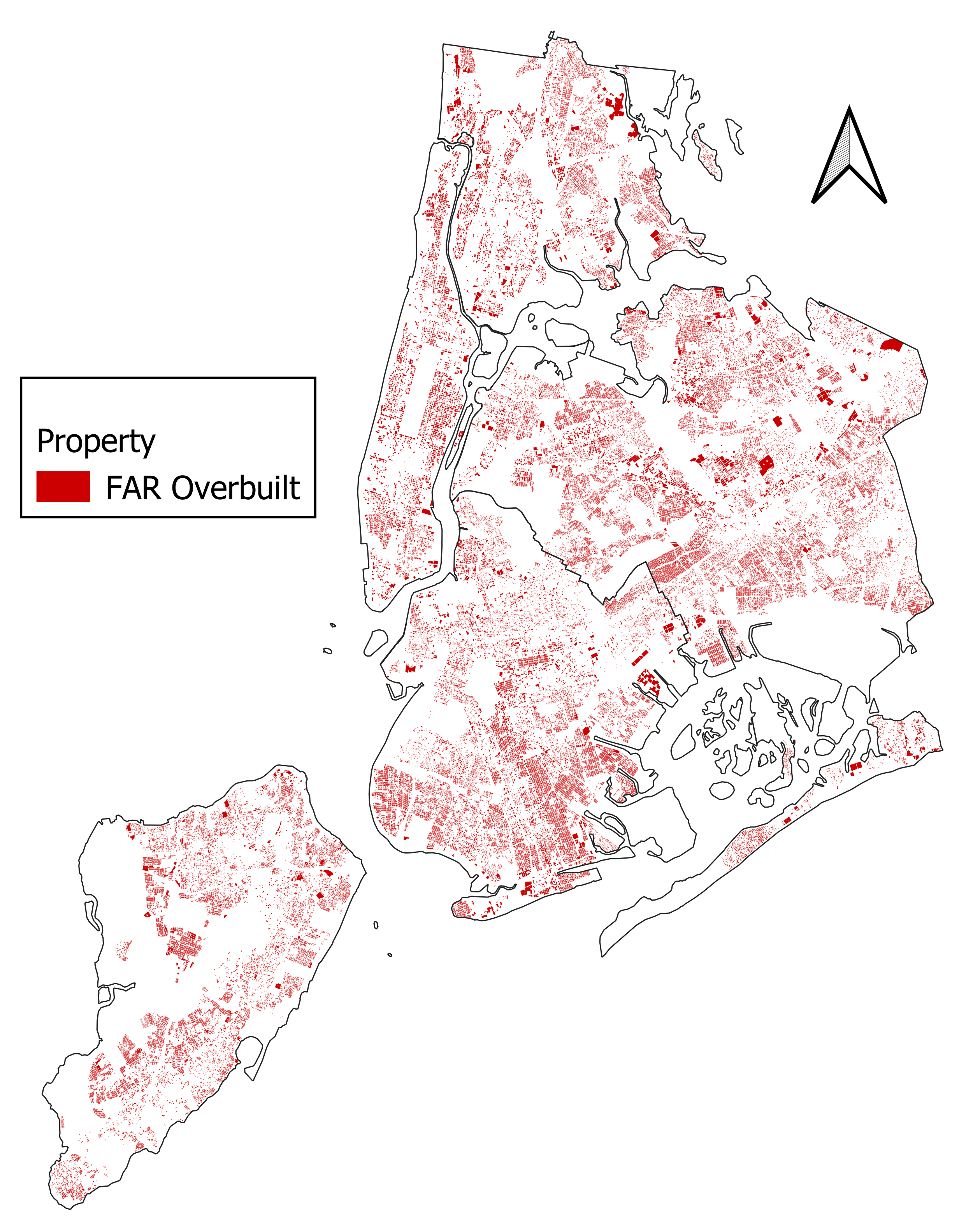

Huie—rightly—complained that the CPC went ahead without any analysis of the plan’s impacts. Moses simply notched the dial downward and left it at that. Huie had performed an analysis and concluded that in the dense business districts, the combined lowering of street wall heights, setbacks, and increasing yard sizes would reduce allowable building floor area by 45%, likely making commercial construction uneconomic. At the same time, he felt that the rules in underdeveloped residential zones were not dialed down enough—and would allow, in his opinion, too much residential density. The best way to fix the problem was to establish Floor Area Ratio (FAR) caps citywide.

The Moses Rebuttal

Huie sent his plan to the Board of Estimate. Moses quickly dashed off a rebuttal lest they get persuaded by Huie’s reasoning. Like a good defense attorney, Moses went through Huie’s points and attacked them as either incorrect or too far-fetched. As for the Floor Area Ratio, implementation citywide would be too risky and have uncertain effects. Besides, Moses argued, you’d still need height caps in the center to control excessive height. On the other hand, Moses’ plan was simple, easily understood, and a mere tweak of rules that had existed for nearly three decades.

Moses Never Sees the Promised Land

When first released, the public reaction to the plan was mixed. Good Government groups, like the Citizens Union and the City Club, endorsed it, while the real estate industry was opposed. The CPC held hearings in June of 1944, then again in July. Moses wanted that to be that, but critics demanded more hearings, and caving to their wishes, the CPC had one more hearing in September. The opponents barked for more delay and study. Nonetheless, on November 1st, the CPC voted 5 to 1 to accept the Moses plan with Huie as the lone dissenter.

Next, it went to the Board of Estimate, which was charged with voting it into law. The Board held hearings on November 15th. Thirty speakers were allowed to voice their opinion, and the majority were against it. Over the next two weeks, opponents and proponents tried to sway the Board. When it held its final vote on November 30th, the majority voted against the zoning revision, with ten votes “nay” and six votes “yea.”[2]

And yet, the CPC had won. To give power to the CPC, the 1936 Charter stipulated that zoning changes approved by the CPC became law unless rejected by three-quarters of the Board of Estimate. In this case, the Board of Estimate rejected Moses’ plan by only 62.5%—not enough to negate it.

Thus, with the 1936 Charter on his side—along with La Guardia’s support—Moses accomplished something that Tugwell could not, or for that matter, had not been done since 1916—a revision of the zoning codes. Or so it seemed….

The 20% Rule

But opponents had an ace up their sleeve—the Zoning Resolution itself, which stipulated the so-called 20% Rule. Section 23 of the Codes on Amendments, Alterations and Changes in District Lines states,

The Board of Estimate and Apportionment may from time to time on its own motion or on petition, after public notice and hearing, amend, supplement or change the regulations and districts herein established….If, however, a protest against such amendment, supplement or change be presented, duly signed and acknowledged by the owners of 20 per cent. or more of any frontage proposed to be altered, or by the owners of 20 per cent. of the frontage immediately in the rear thereof, or by the owners of 20 per cent. of the frontage directly opposite the frontage proposed to be altered, such amendment shall not be passed except by the unanimous vote of the Board. (Emphasis added.)

In other words, if a rezoning was protested by 20% of affected property owners, it could only pass if the Board of Estimate approved it unanimously. The matter was brought to the courts less than a month after Moses’ apparent victory, and the plan officially died in July 1946.

As Makielski writes,

The result was almost anticlimactic….[T]he State Court of Appeals held that “20 per cent rule” applied and that clearly the Board of Estimate had failed to pass the amendment by unanimous vote….The Planning Commission had won before the Board of Estimate…but was defeated by another “formal rule” of the game; a rule that demonstrated the importance of the Borough Presidents’ votes when coupled with an energetic opposition to zoning innovation. Moses characteristically commented on the outcome, “Apparently we were too far ahead of the procession.”

Robert Dowling—the man that Moses accused of lying—led the lawsuit and had the last laugh when he “took a slap at Mr. Moses by referring to protests ‘ruthlessly ignored by certain public officials who resent any disagreement with their opinion….’,” as reported the New York Times.

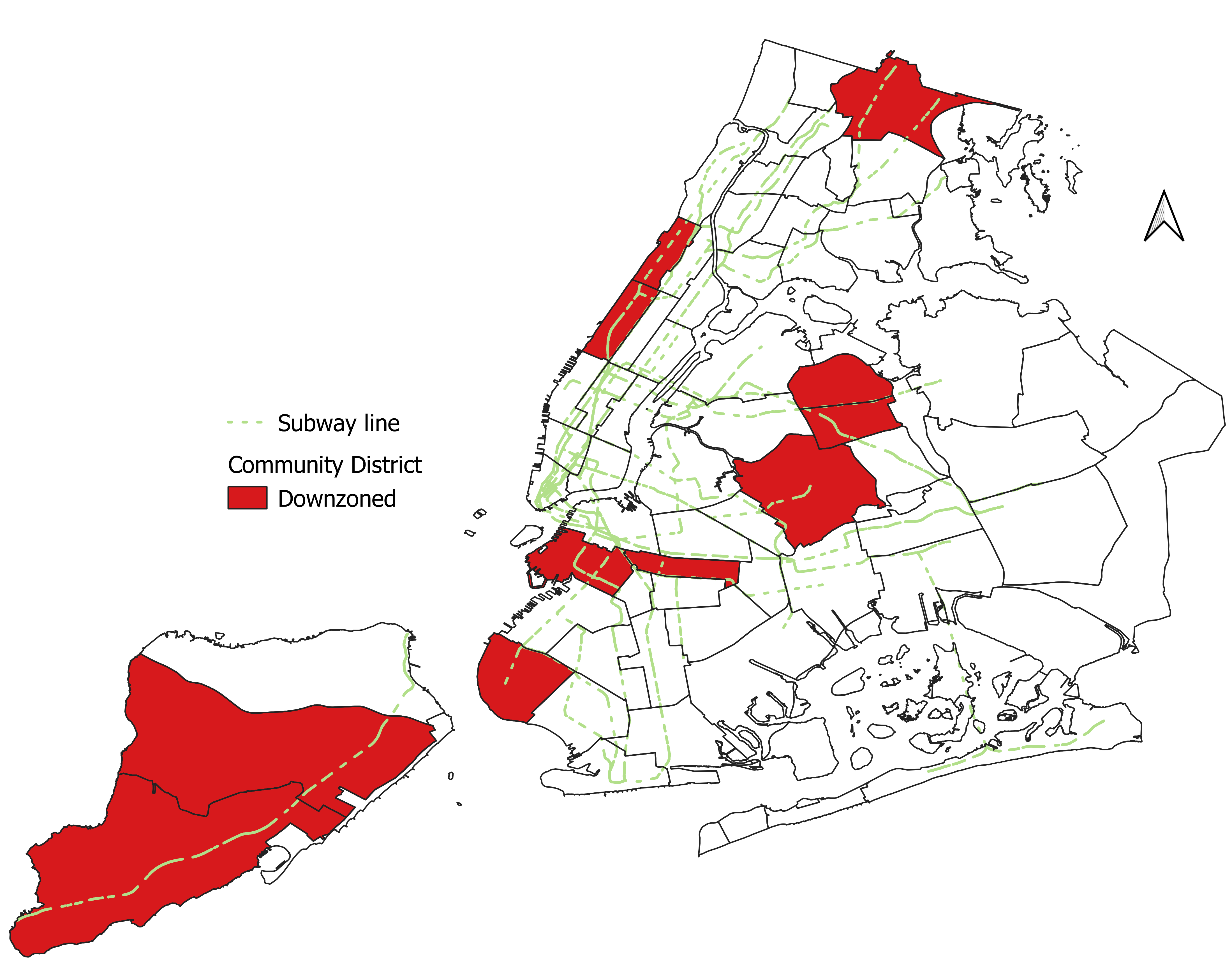

The Moses Effect

Moses’ defeat, in part, represented the triumph of parochialism. The Borough Presidents of the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island voted against his plan. This fact, along with the 20% rule, meant that even Moses did not have enough power to overcome local interests. But at the same time, Moses was not interested in building coalitions and forging common interests like Edward Bassett did when formulating the 1916 Resolution. For Moses, it was his way or the highway; in the end, that was his undoing in 1944.

His failure also meant the continuation of the status quo—the 1916 Resolution—for the foreseeable future, which, depending on where you sat, was either good or bad. But more broadly, Moses’ defeat also shows that, in its early years, the City Planning Commission proved ineffective in achieving its own goals. Whether it was the grand dreams of Tugwell’s Master Plan or Moses’ simple rezoning, the City Planning Commission failed to establish power over land uses and to find the right balance between growth and change and protection and preservation. This legacy continues into the 21st century, where the idea today of wholesale rezoning is virtually impossible.

FAR Away

Because of Moses’ antipathy toward using the Floor Area Ratio, a full-scale rezoning of the city would have to wait until he was out of power. But over the years, the ideas of those on the left would become increasingly mainstream. As I will document in the next post, the CPC would take up a full-scale rezoning in 1950, and the battle to tame Gotham would continue once again.

Read the first post in the series here.

—

[1] As a side note, Moses appears to utter these statements without a hint of irony, which is rich given that throughout his long career, he was not above using sneaky or underhanded methods to achieve his ends.

[2] The Borough Presidents of the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island were against it, and the citywide officers and the Borough President of Queens voted in favor. On the Board, citywide leaders each had three votes, the borough presidents of Manhattan and Brooklyn had two votes, and the other borough presidents each had one vote.