Jason M. Barr August 14, 2023

Many cities around the world have severe housing affordability problems. One reason is overly restrictive zoning regulations. Zoning—the rules that dictate what can be built on each lot—was initially designed to control urban problems, including congestion, pollution, and shadows.

Over time, however, planners made common cause with property owners to tighten the rules. Planners did not like urban density and were all too happy to reduce it. Property owners realized that stricter codes could preserve their property values and exclude the poor and minorities from their neighborhoods.

By the middle of the 20th century, the most popular zoning rule was limits on the so-called Floor Area Ratio (FAR)—the permitted maximum floor area stated as a ratio to the lot size. For example, a maximum FAR of 1 means a one-story structure can cover the entire lot or a two-story structure can be built on half the lot. FAR caps and plot coverage maximums guarantee much lower population densities.

A Bridge too FAR?

The decades of downzonings—reductions in allowable FARs—after World War II, however, did not affect housing prices all that much since large industrial centers were emptying out, and the suburbs still had plenty of land on which to build. But then, in the 1990s, these places began to rebound. A recent wave of research, particularly in economics, has documented the unintended consequences of stringent zoning regulations, including higher housing prices, increased segregation, urban sprawl, and greater greenhouse gas emissions.

If the 20th century was the Age of Downzoning, then the 21st century is gearing up to be the Era of Upzoning. Cities worldwide have initiated loosening building regulations. Logically speaking, if downzoning has reduced construction, then upzoning should produce more housing. Or does it? Does simply turning on the spigot cause the water to flow?

Let there be Housing?

To answer this question is not so simple, however. One must be able to see clearly through the fog of urban change. Expensive cities are dynamic places: people constantly move in and out, and businesses grow and shrink. Housing affordability seems to worsen no matter what new policy or subsidy the government adds.

The typical observer sees the tall cranes erecting luxury condos while urban life gets more expensive. It must logically follow that those cranes are “causing” higher prices. However, demand and supply are in a constant wrestling match. When the demand side wins, prices rise, no matter how much new construction there might be.

The Scientific Method

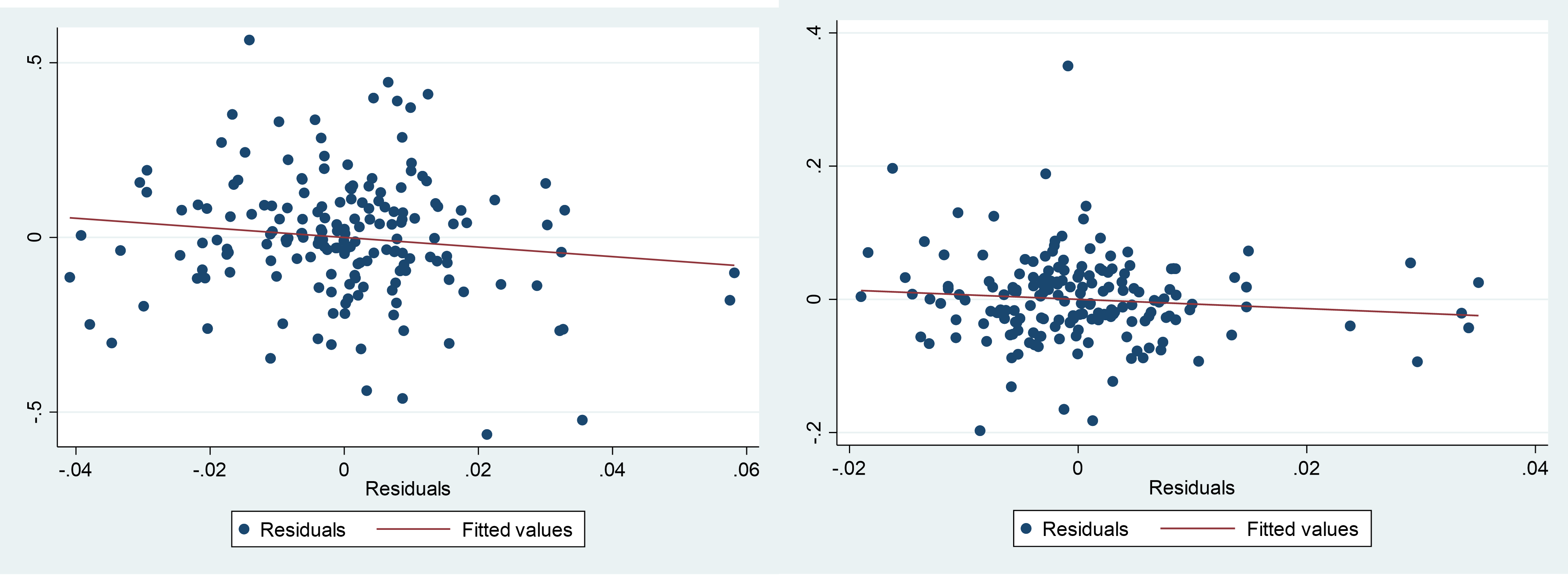

To separate supply from demand and cause from effect requires some effort. Researchers must create a scientific setup—a treatment and control framework—especially concerning changes to the zoning rules. If particularly hot neighborhoods are targeted for upzonings, there needs to be a way to identify the demand (the hotness) from the upzoning impacts (more supply).

For example, when testing a new pill that aims to lower cholesterol, it’s best to compare a group of people with similar characteristics. The ideal experiment is to enroll in a study, say 100 men, who are very similar—in their 50s, overweight, and don’t regularly exercise. Half are randomly assigned the pill, while the rest are given a placebo. If the men who took the pill have lower cholesterol, on average, it strongly suggests that the pill works.

Zoning as Treatment

Recent studies on upzoning, discussed below, use this logic, although, unlike medical doctors, researchers can’t control the experiment to such a fine degree. Instead, they need a way to locate a reasonable control group similar to the “treated,” or upzoned, lots before the upzoning was enacted.

Several studies use the so-called border method. They compare blocks in the upzoned area to those just on the other side. Presumably, two blocks across the street are very similar otherwise. Another approach uses time as the difference. When areas are rezoned randomly at different times, one can compare neighborhoods before and after the rezoning. Finally, another method is to use a statistical algorithm to match upzoned parcels to similar non-upzoned parcels elsewhere in the city.[1]

With this in mind, we now turn to the findings.

Upzonings Around the World

New York

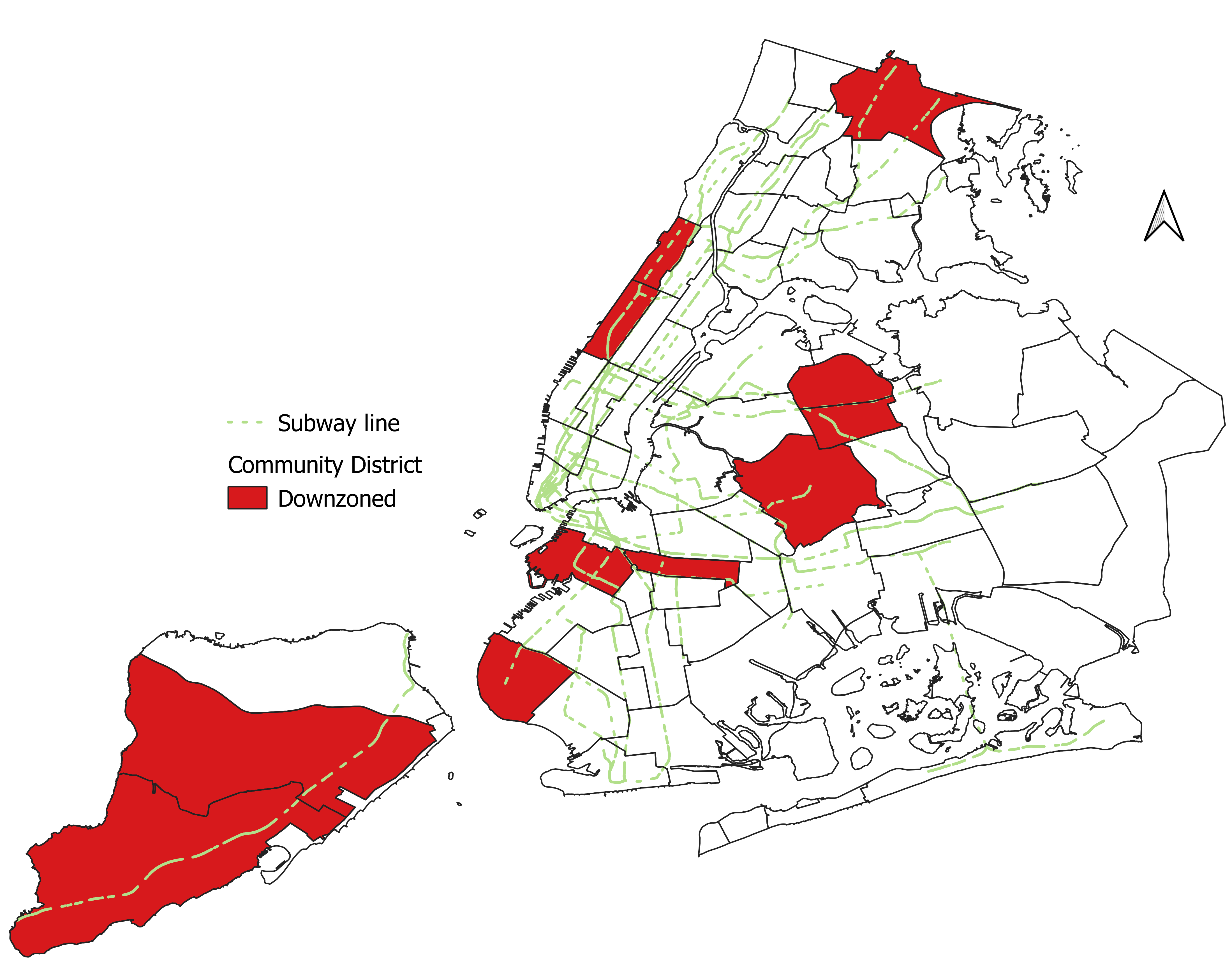

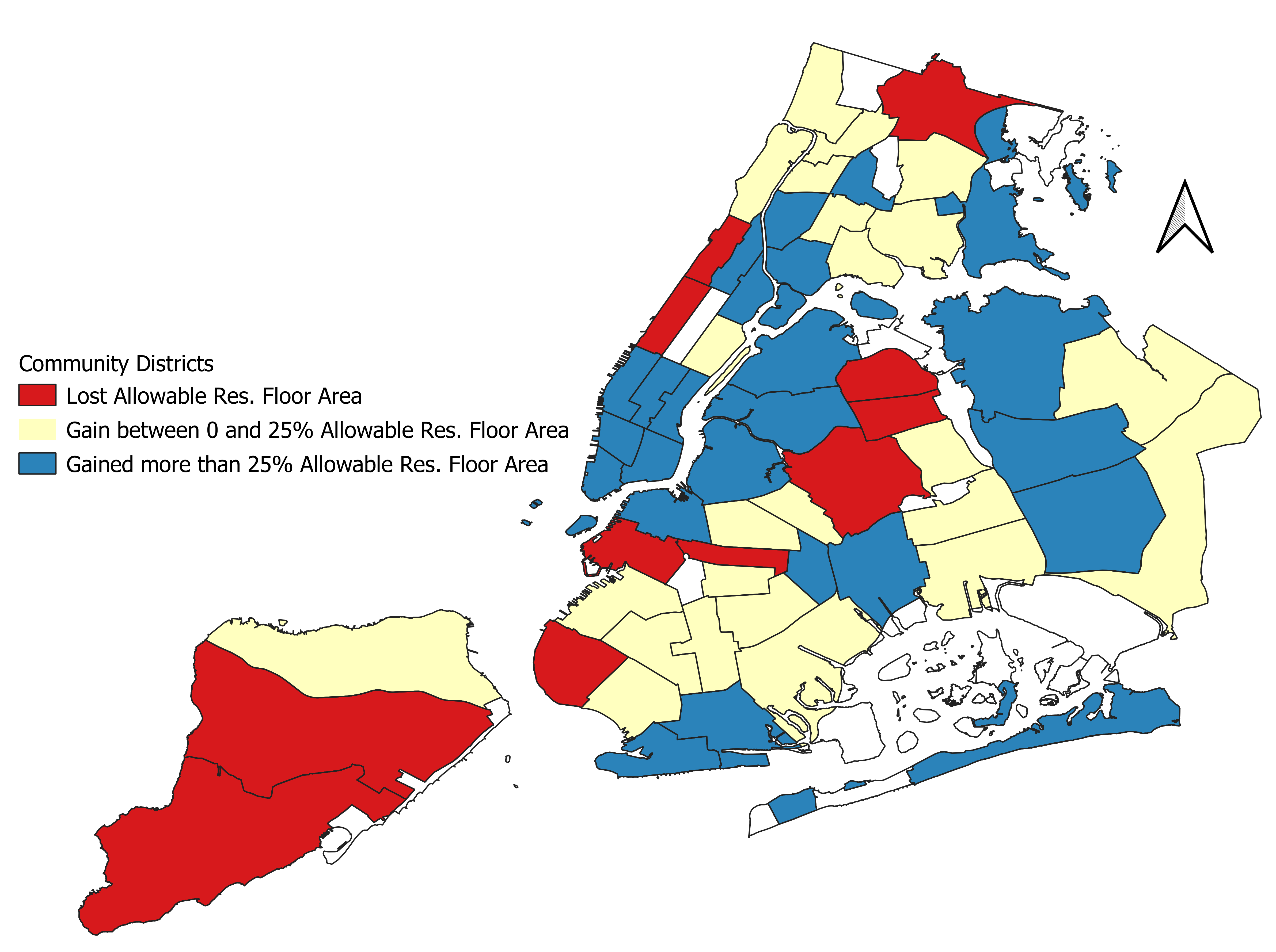

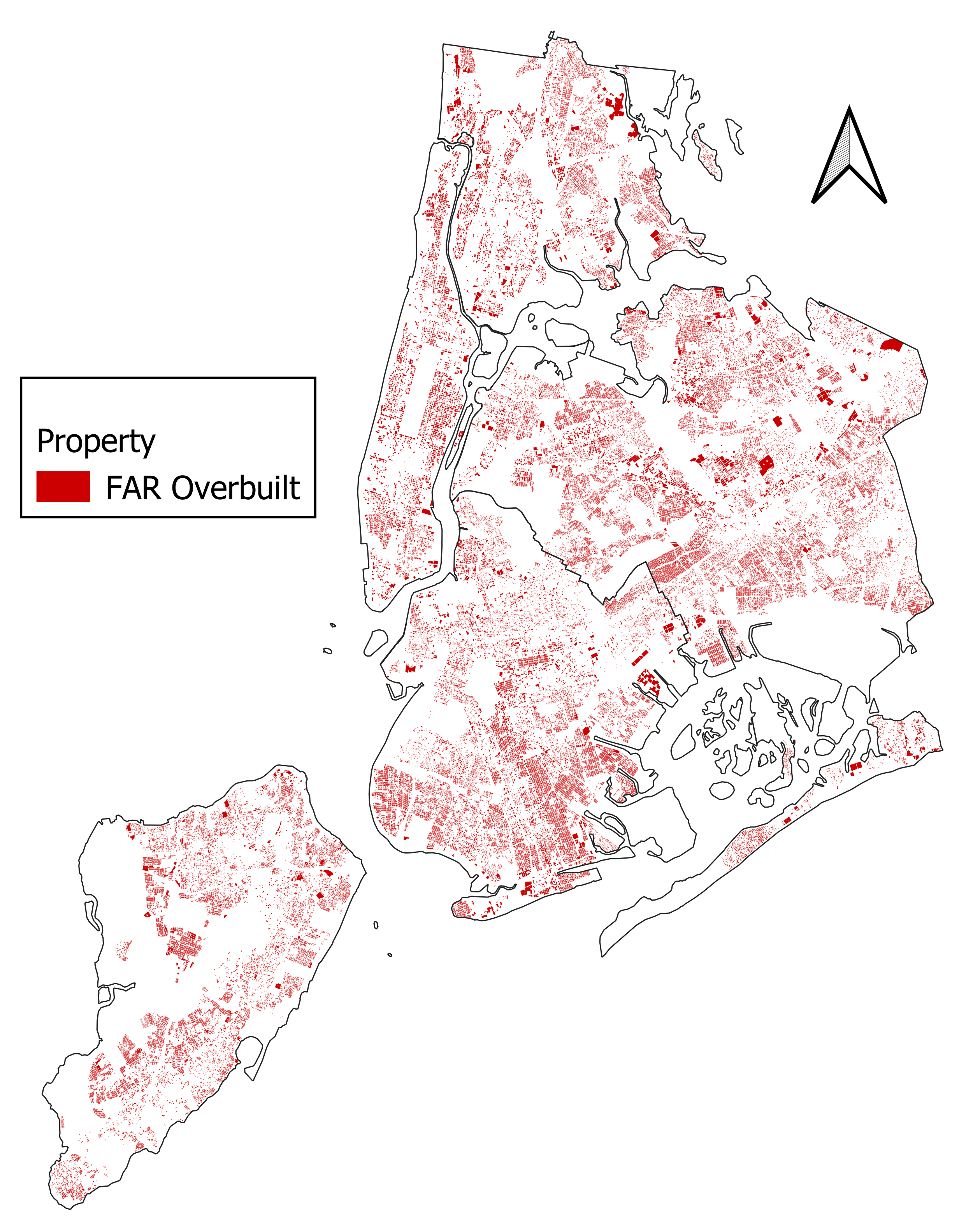

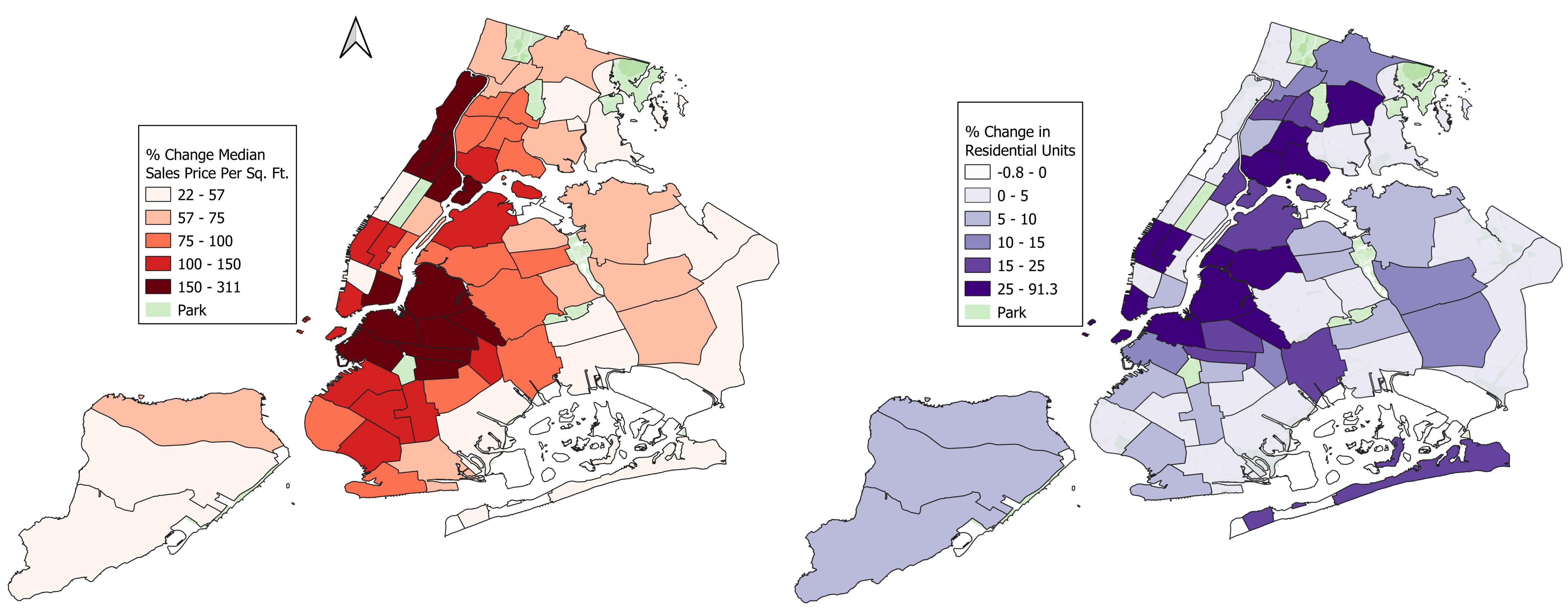

New York City, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, from 2004 to 2013 rezoned nearly 40% of the city’s residential land. Central areas of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and western Queens, which had underutilized industrial sites, waterfront blocks, and transit-accessible neighborhoods, were upzoned by increasing the maximum allowable FAR for residential use.

Hsi-Ling Liao, in her 2023 paper, “The Effect of Rezoning on Local Housing Supply and Demand: Evidence from New York City,” compares upzoned parcels to those that were not upzoned but were within 1000 feet (305 m) of the boundary. She concludes that in the upzoned districts, “…the number of residential units increased by more than 4 percent seven years after upzoning. The parcels that are more intensively treated and receive a stronger boost in allowed residential capacity experience an 8 percent increase in housing supply.”

A very similar study was conducted by Xuequan Elsie Peng in her 2023 paper, “The Dynamics of Urban Development: Evidence from Land Use Reform in New York.” She compares the new housing units in the upzoned blocks to those that are within 650 meters away (0.4 miles). Her findings echo those of Liao’s—in the upzoned areas after six years, the number of units increased by about 4%, while after 12 years, the number of units increased by about 8%, relative to the blocks that were not upzoned.

Peng also studies treatment intensities by investigating if more generous FAR allowances lead to more housing. She finds that in the low upzoning case (FAR increases of less than 30%), there was about 2% more housing, on average, after ten years relative to the non-upzoned blocks. In the high upzoning case (FAR increases greater than 92%), she finds that these neighborhoods added about 8% more housing, on average, after ten years than non-treated blocks.

Portland

Hongwei Dong, in his 2021 paper, “Exploring the Impacts of Zoning and Upzoning on Housing Development: A Quasi-experimental Analysis at the Parcel Level,” studies the case of Portland. He focuses on parcels that were upzoned between 2001 and 2002 in southwestern Portland. In this case, the rezonings were primarily in suburban neighborhoods, where a majority of lots contained low-density, single-family homes.

After matching upzoned parcels to similar non-upzoned ones, Dong concludes that upzoned parcels were about two times more likely to be developed fifteen years after upzoning and that “further analysis suggests that the 111 upzoned parcels produced 240 dwelling on 33.8 acres of land. The density is 7.1 units per acre. The fifty-eight control parcels produced eight dwelling units on 18.6 acres of land. The density is 4.3 units per acre. These findings suggest that upzoning not only sped up housing developments but also increased housing production.”

Seattle

Jacob Krimmel and Betty Wang study the case of rezonings in Seattle in their 2023 paper, “Upzoning with Strings Attached: Evidence from Seattle’s Affordable Housing Mandate.” Unlike New York and Portland, Seattle took a different approach. In 2019, select neighborhoods were upzoned to allow more floor area, but this benefit came with a “tax”—a mandatory housing affordability (MHA) requirement for developers to either include affordable units or pay into a fund for the city to spend on affordable units elsewhere. The authors write, “The reform combines two policy levers that some economists consider to conflict with one another: Increasing development capacity through upzoning and requiring private development to create income-restricted affordable housing.”

The MHA areas were applied to areas already zoned for multifamily, commercial, or high-density single-family homes (such as townhouses). However, the upzoning was relatively mild, amounting to one additional floor than otherwise, on average. Comparing blocks that were in MHA areas to those that had no change, they conclude that the program, in fact, backfired in that it drove new construction away from the MHA areas. They find

strong evidence of developers strategically siting projects away from MHA-zoned plots – despite their upzoning – and instead to nearby blocks and parcels not subject to the program’s affordability requirements. The differential reduction from MHA to non-MHA zones could be as large as 70% of average permitting activity at the border.

They further find that:

Worryingly, most of the drop in the number of units in MHA zones is coming from the multifamily segment of the market, where most of the housing products are 3- and 4-story townhouses and duplexes. This is of particular note because lowrise and small multifamily homes are seen as a more affordable alternative to luxury apartments for low- and moderate-income renters.

Chicago

In “Upzoning Chicago: Impacts of a Zoning Reform on Property Values and Housing Construction” (2019), Yonah Freemark explores the case of Chicago. Under Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Chicago undertook two rounds of upzonings. The first, in 2013, upzoned neighborhoods between 600 feet (183 m) and 1,200 feet (366 m) of metro and commuter rail line stops to encourage transit-oriented development (TOD). The second round, in 2015, expanded the upzoned areas to a half mile within the stops.

The rezonings involved two types of changes. The first was an increase in the allowable FAR, which in 2013 amounted to 17%, on average, while the 2015 rules increased the FAR from before 2013 to 33%, on average. Additionally, in both years, rules on on-site parking were made less stringent, allowing developers to provide fewer spots.

Freemark first compares parcels upzoned in 2013 to those left unzoned but were later upzoned in 2015. He then compares the parcels upzoned in 2015 to neighboring blocks just outside. For the 2013 upzonings, Freemark does not find evidence that they led to an increase in housing supply, as measured by new building permits.

However, this finding is likely due to three factors. First, the upzonings applied to both high- and low-income areas. Upzoning low-income areas is less likely to be effective if the income there is not high enough to compensate for the cost of new construction. Second, the period of investigation was from late-2013 to late-2015, a very short period to analyze the impacts of upzoning. Lastly, the average upzoning of 17% was rather small to have a meaningful impact, as other studies have shown.

However, in his analysis of the impact of the more generous 2015 upzonings, he finds (weak) evidence that the combined relaxation of parking and FAR rules increased the number of residential building permits in the nearly-three-year period after the rules changed (about 25 more permits in the upzoned areas versus the non-upzoned areas between September 2015 and June 2018).

Zurich

In their 2023 paper, “Making Housing Affordable? The Local Effects of Relaxing Land-Use Regulation,” Simon Büchler and Elena Lutz investigate the Canton of Zurich in Switzerland from 1995 to 2020. The canton contains 168 municipalities with a population of 1.52 million. Each municipality separately undertakes rezoning approximately every 15 years.

The authors exploit the independent and random timing of the rezonings to explore how increases in the FAR before and after the rezonings impact housing construction in 100-meter (328 feet) by 100-meter grid cells. For each cell, they measure the total floor area in five-year intervals and then track when the upzonings occurred. Thus, the treatment is the cell after upzoning, and the control is the cell before upzoning.

Their conclusion: “We find that large upzonings of more than 50% significantly increase the living space and housing units by 9-18% on upzoned parcels compared to non-treated parcels in the subsequent six to 15 years….In contrast, small upzonings, of 0-50%, do not incite a strong reaction from developers.”

Auckland

In their 2023 paper, “The Impact of Upzoning on Housing Construction in Auckland,” Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy and Peter Phillips study upzoning in Auckland, the largest city in New Zealand, with about 1.57 million residents. In 2016, the metropolis upzoned nearly three-quarters of its residential land.

The authors’ approach is to look at new building permits inside the upzoned areas versus those just outside. Studying the relative changes in annual building permits issued for new dwelling units, they conclude,

The response to the zoning change is immediate: The estimated treatment effects increase every year after implementation. By 2021, five years after the policy was introduced, some 23.06 additional permits are issued, on average, in upzoned areas compared to non-upzoned areas in each of the 479 Sas [Statistical areas, similar to census tracts]. This would correspond to 11,044 permits across the city. Cumulating the corresponding figures for 2016 through 2021 yields 34,614 additional permits in upzoned areas compared to non-upzoned areas. Treatment effects for attached dwellings exceed detached from 2019 onwards. By 2021, the estimated treatment effect for attached is 17.96 permits, while for detached it is 5.09.

São Paulo

Finally, in their 2023 paper, “Estimating the Economic Value of Zoning Reform,” Santosh Anagol, Fernando Ferreira, and Jonah Rexer study the case of São Paulo, the world’s fourth largest city, with 21 million residents in its metro area. The city undertook a rezoning in 2016. Similar to the other studies, they explore how raising the Floor Area Ratio—what they call the Built Area Ratio (BAR)—impacted new construction. On average, they found that the upzoning increased the allowable BAR by 36%, and more than half the city’s blocks received an increase.

The authors explore new housing permitting in upzoned blocks compared to non-upzoned blocks on the other side of the border. Their conclusion:

We find that the 1.4-point max BAR increase at the cut-off causes an increase of .003 multi-family dwelling permits filed per block per quarter, which is a sixty six percent increase in permits per unit of max BAR in treated relative to nearby control blocks. The differences in permitting activity between treatment and control blocks emerge just one year after the zoning reform was passed and increase thereafter, which is plausible given the time it likely takes for developers to create project plans, acquire land, and so on.

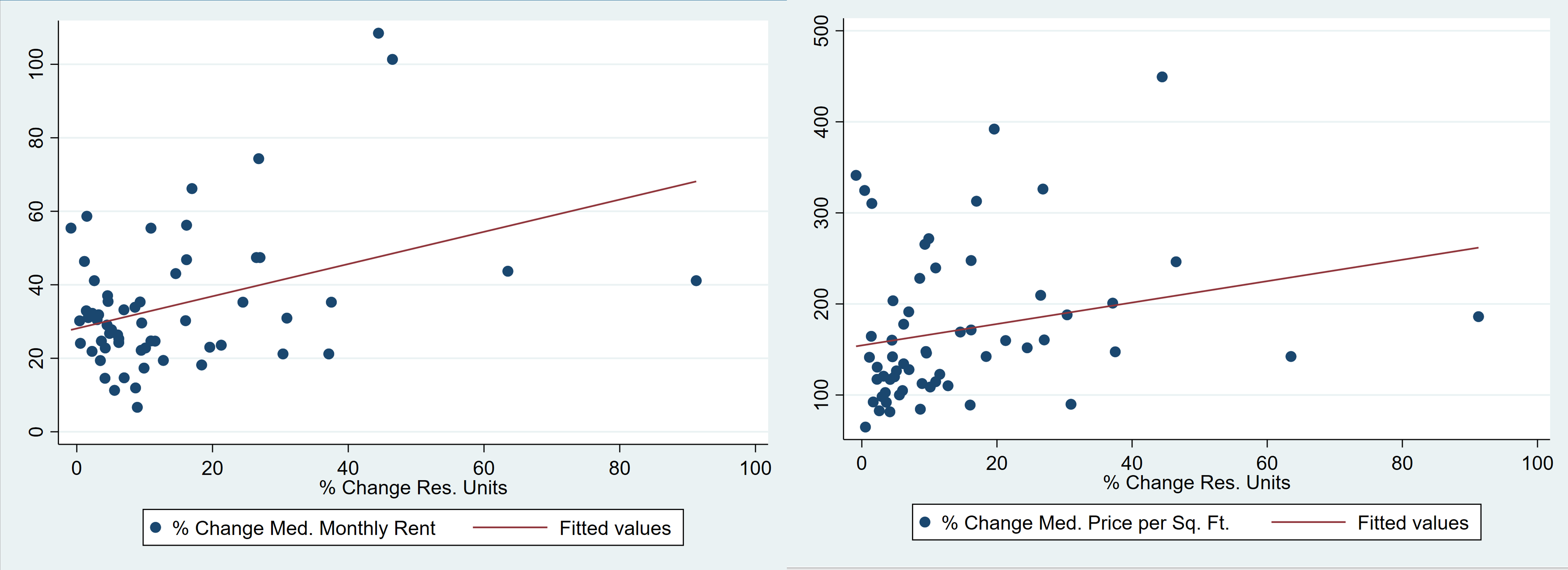

Upzoning and Housing Prices

Several studies also look at the impact of upzonings on real estate prices. Here the findings are mixed. However, interpreting price impacts is more complex. When rezonings occur, several processes are at work. The first is that upzoned parcel has the future opportunity—the so-called option value—to be redeveloped more densely and generate more revenue. A forward-looking market naturally means that upzoned parcels will sell at a premium, even if there is no redevelopment in the short run.

Second, upzoned neighborhoods typically mean more density, which means more Starbucks and other urban amenities, which raises local housing prices. There’s also the possibility of the opposite effect, where density causes more traffic congestion, street noise, crime, or trash—a so-called negative amenity effect—which will reduce prices (however, I sense is this is less of an issue today).

Then there is the supply effect: more housing will reduce prices, all else equal. However, when upzonings are small and take a long time to yield fruit, the supply effect may be swamped by the option value and amenity benefits.

The Findings

Liao’s study of New York City looks at the sale prices of buildings built before 2004 and thus excludes any buildings completed after the rezonings. She finds no statistically significant changes in housing prices in the upzoned areas, suggesting that the supply effect balanced out the amenity and option value effect.

Freemark’s study of Chicago found that after the upzonings in 2013, density bonuses increased prices by about 16%, on average, vis a vis the non-upzoned parcels. But focusing on location, he finds that the result was likely driven by price rises only in Downtown, with no increases in other neighborhoods. And zooming in only on condo sales, he finds that prices increased by 12%, on average. Since the period of his analysis was short, it suggests that Downtown condo buyers had higher expectations for their neighborhood that showed up quickly in the sale prices but were not offset by more supply.

Büchler and Lutz’s study of Zurich looks at average rental listing prices. They found that rental prices in upzoned cells typically saw no price changes over time. Again, the supply effects of lower rents were evidently matched by the amenities benefit.

Anagol et al. look at neighborhood housing prices for São Paulo and find that areas with larger BAR increases had greater increases in the number of home sale listings, where a 1-point increase in the maximum BAR was associated with a 10.9% increase in listings growth, on average. And just as importantly, with more listings and supply, they found that each one-point increase in maximum allowable BAR was associated with a 5.7 percentage point reduction in home prices.

All told, these studies suggest that price impacts hang in the balance between the different supply and demand forces, but they also demonstrate that price increases are not a foregone conclusion.

Does Upzoning Work?

This research shows that, yes, upzoning works. Of the seven studies reviewed here (excluding the Krimmel and Wang study), all but one found a statistically significant uptick in new housing permits, completed units, or residential floor areas after upzonings—and because of the upzonings.

But, of course, there are nuances and caveats. The studies reveal that the units materialize only after several years, and their impacts are relatively modest. But they do show that if strategically managed, upzonings can be effective.

What are the key lessons from these studies?

Scale

The first is that scale matters—the greater the allowable floor area increases, the greater the impact the upzoning will have. For example, Liao and Peng found that small FAR increases yielded much less housing for New York than larger FAR increases. Büchler and Lutz found no effect in the Canton of Zurich for upzoning of less than 50% but saw about a 10% increase after ten years for large upzonings. In Chicago, upzonings of 33% seemed more effective than of 17%. And Krimmel and Wang show that mild upzonings with additional costs can backfire by diverting construction away from these areas.

Scope and Location

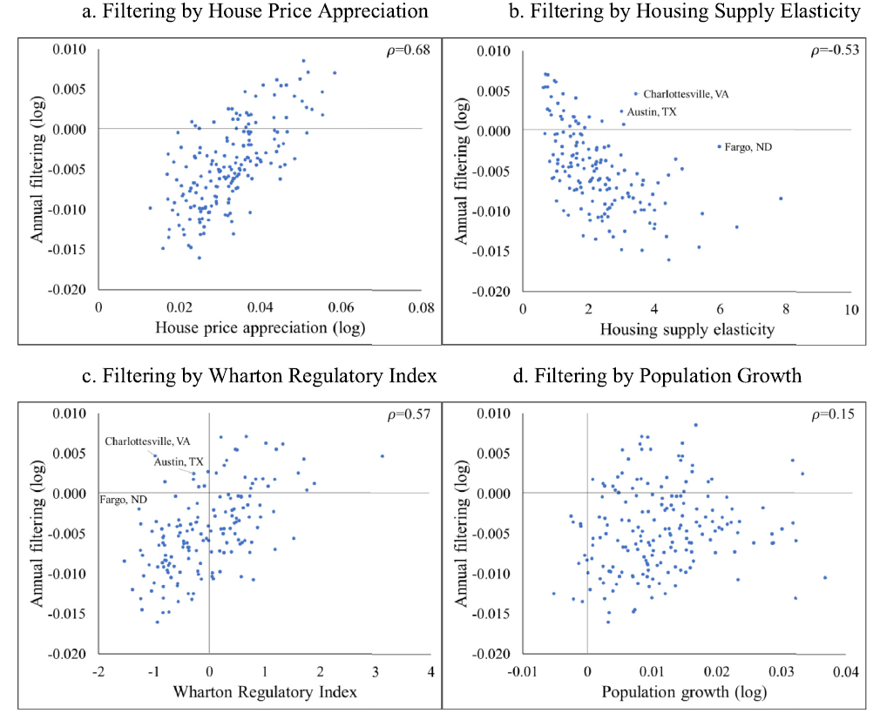

While these studies do not directly investigate the amount of total upzoning versus total new supply, the evidence suggests that broader is better because of housing supply’s connection with demand. In central neighborhoods, a new high-rise can trigger an upward price spiral because of the national or international demand.

Outside of the center, where demand is more tempered, and land values are lower, new supply will be more easily felt because the new tenants are less likely to trigger an upward price cycle. On the other hand, in locations where the cost of new construction is too high relative to the expected rents or incomes, upzonings may have little effect. Districts with high owner-occupied and single-family homes will likely also see slower impacts because redevelopment can only occur once owners decide to move, which can take several years.

These studies focus only on upzonings. But many cities downzoned some neighborhoods simultaneously with their upzonings. As a result, rezonings can wind up shifting supply rather than boosting it citywide. And if rezonings push construction from the periphery to the center, price relief may not result.

An Affordable Future

Upzoning is necessary for a healthy city to grow and accommodate more residents, but it is not sufficient to solve the affordability problem. Older, denser cities still have a host of other barriers or frictions that make new construction difficult and slow, particularly in neighborhoods where it’s needed most.

Parcels must be assembled, buildings must be emptied, and other building regulations must still be followed—producing a steep mountain to climb.

Greasing the Wheels

In other blog posts, I have discussed steps that cities can take, but let me highlight a few that can help grease the wheels:

- Link upzonings to neighborhood housing vacancy rates. The lower the vacancy rates, the more generous the increases in the FAR. This will ensure that upzoning is applied where it’s needed most.

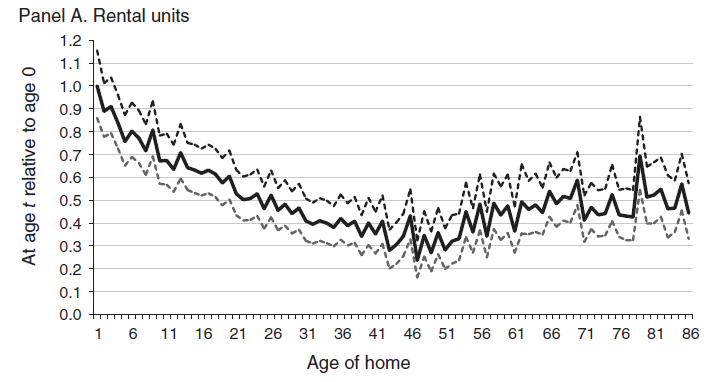

- Construction subsidies should be the greatest in the middle- and moderate-income neighborhoods. Abundant affordable housing comes from the construction of middle-income housing outside the center. Lower-income residents will gain through the so-called filtering process, where the older housing becomes more affordable, and people move into the new middle-income housing.

- Homeowners should have much more flexibility to add Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), such as converting a garage to an apartment, adding a “granny flat” in the yard, or subdividing their house to add an apartment. These new units, which don’t require demolitions or evictions, are a relatively easy way to provide affordable units and generate extra income for homeowners in the suburbs.

- A land value insurance program can insure homeowners against reduced land values if rezonings should cause neighborhoods to become less valuable. This will reduce (though not eliminate) NIMBYism since residents have some economic protection against change.

Leadership

The real problem of housing affordability, however, is not economics, it’s politics. Upzonings are contentious because people see them as generating higher housing prices and bringing changes to their neighborhoods. As a result, they elect leaders who either enact NIMBY policies or merely tiptoe through the garden of affordability.

True affordable housing comes from expansive citywide policies. The only way to do this is for leaders to form coalitions, seek compromise, create carrot-and-stick programs, and compensate those harmed to prevent them from stopping reforms.

Our cities cannot afford the delay.

Works Discussed

Anagol, S., Ferreira, F. V., and Rexer, J. M. (2023). “Estimating the Economic Value of Zoning Reform.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w29440.

Büchler, S., and Lutz, E. C. (2023). “The Local Effects of Relaxing Land Use Regulation on Housing Supply and Rents.” Working Paper (July).

Dong, H. (2021). “Exploring the Impacts of Zoning and Upzoning on Housing Development: A Quasi-experimental Analysis at the Parcel Level. Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Freemark, Y. (2020). “Upzoning Chicago: Impacts of a Zoning Reform on Property Values and Housing Construction.” Urban Affairs Review, 56(3), 758-789.

Greenaway-McGrevy, R., and Phillips, P. C. (2023). “The Impact of Zoning on Housing Construction in Auckland.” Journal of Urban Economics, 136, 103555.

Krimmel, J. and Wang, B. X. (2023). “Upzoning With Strings Attached: Evidence from Seattle’s Affordable Housing Mandate.” Working Paper (July) and summary in Cityscape (2023).

Liao, H-L (2023). “The Effect of Rezoning on Local Housing Supply and Demand: Evidence from New York City.” Working Paper (July).

Peng, X. E. (2023). “The Dynamics of Urban Development: Evidence from Land Use Reform in New York.” Job Market Paper (January).

—

[1] The matching method used by Dong is called propensity score matching. The rest of the papers used what is called Difference-in-Difference (DiD) regressions.