Jason M. Barr July 16, 2019

Note this is Part I of an on-going series on the evolution of skyscraper technology. The rest of the series can be found here.

The Birth of Height

In 1900, the architect Cass Gilbert—who later designed the 55-story Woolworth Building (1913)—wrote an article to justify the existence of tall buildings. At the time, New Yorkers were witnessing their first skyscraper boom. They were curious and puzzled, and unsure of what to make of these new structures. Since the dawn of civilization, buildings for work and living were never more than six stories. Then, in a matter of a few short years, offices of 10, 15, and even 20 stories were appearing with alarming frequency.

In an understated tone, Gilbert wrote that the tall building was “merely a machine that makes the land pay.” He implicitly argued that the tremendous economic forces drawing businesses together into Lower Manhattan were driving land values upward. Finance and insurance companies, transportation and communication firms, importers and exporters, corporate headquarters, publishers, law firms, etc., etc., were tightly clustered in Manhattan’s lower toe in order to sell their products and be close to the port.

Emergence

High land prices meant that if a landowner wanted a reasonable return on his investment, he needed to find a way to generate more revenue from the lot. The solution: build taller. With more floors comes more rent. In the history of cities like New York and Chicago, the skyscraper was a naturally emergent phenomenon. Expensive land values incentivized developers, engineers, and architects to produce cost-effective technologies to create new “land” where it was needed most. Thus, in the 1880s, the skyscraper–land in the sky–was born.

Positive Feedback

Once the technology of tall was possible, it generated a positive feedback loop: highrise buildings created more economic growth, as they allowed for more firms to be at the same place and the same time, which increased land values and incentivized builders to improve the technology that allowed them to go even taller. But skyscrapers, by their very nature, also represent public displays. Businesses and developers realized they could use height to convey additional information, such as corporate advertising or to signal their success.

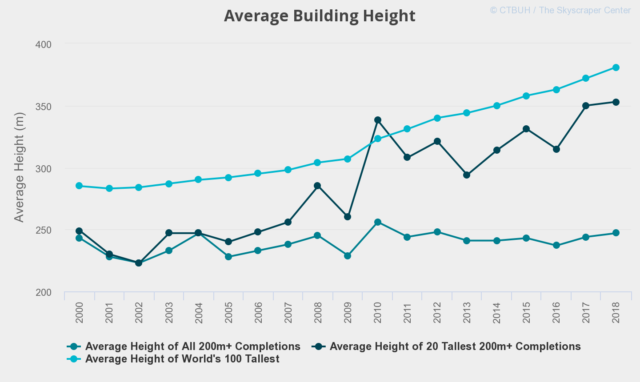

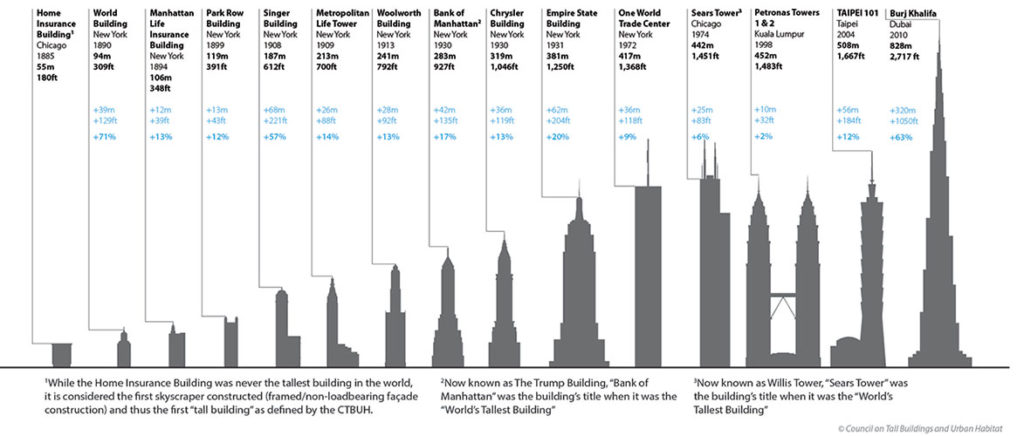

As a result, between 1890 and 1931, the world’s tallest building grew from 94 meters (350 feet) to 381 meters (1250 feet), for an average annual growth rate of 6.3%. The Great Depression and World War II halted the demand for tall buildings for 15 years. Then, as the world cleaned up its mess, tall buildings began to rise again. It wasn’t until the 21st century, however, that the skyscraper became truly a global phenomenon.

Globalization and the World’s Tallest Buildings

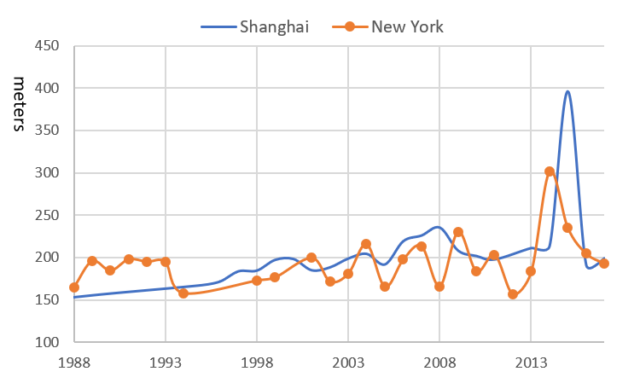

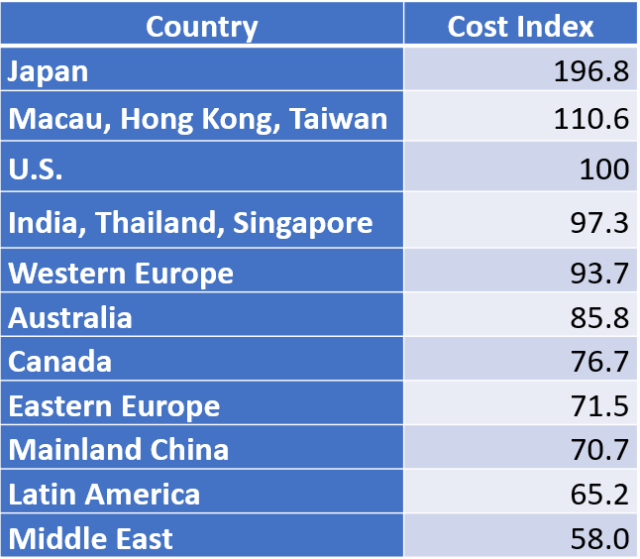

Rapid urbanization, globalization, and economic development created new wealth for formerly low-income countries. This, then, permitted cities and nations around the world to embrace skyscraper construction, not just as a response to economic conditions, but also as an engine for economic growth. That is to say, building innovations combined with rising global incomes meant that skyscrapers could be used as drivers of urban growth and as part of deliberate urban planning strategies to create new places and new industrial clusters. This is particularly the case in Asia, where skyscrapers have been used to turn the world’s focus eastward.

Rise of the Supertalls

Arguably, the first time any government took an active role in the construction of the world’s tallest building was in New York in the 1960s. Lower Manhattan, an aging business district, had fallen on hard times. The Twin Towers, completed by 1973, became part of a deliberate effort by a local government agency—in this case, the Port Authority of New York and NJ (PANYNJ)—to build and operate the world’s tallest buildings, and to revive what was essentially the world’s first skyscraper district (in parallel with Chicago’s Loop).

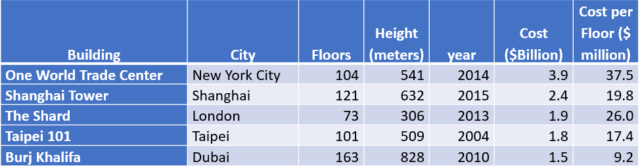

Although, architecturally speaking, New Yorkers were ambivalent about the towers, the structures took advantage of new innovations that made this kind of height economically feasible (similar technology was used for the Sears (Willis) Tower). Then, starting in 1998 with the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, all of the world’s record-breaking buildings were promoted by government officials to boost the visibility of their respective cities—Taiwan (the Taipei 101, 2004), Dubai (the Burj Khalifa, 2010), and, next up, Jeddah (the Jeddah or Kingdom Tower, 2020).

In short, the competitive pressures of economic growth, along with the existence of a large industrial organization of engineers, architects, suppliers, general contractors, and financial institutions, have allowed new cities to get into the height game. These cities have taken advantage of, and have driven, new technological innovations that allow buildings to be both taller and less expensive. We now turn to the evolution of some of this technology.

The Gravity Problem

In the old days, before the advent of skyscrapers, most large buildings had load-bearing masonry walls. That is, the walls held up the building. But over the course of the 19th century, as the demand for taller and bigger structures increased, these walls needed to be proportionally thicker at the base. This presents two problems. First is that thicker walls reduce access to internal light. Second, at some point, especially on narrow lots, the thickness of the walls at the ground floor would remove much of the usable space, and was therefore not an economical use of the land. For example, Chicago’s 16-story Monadnock Building (1893) was the world’s tallest masonry load-bearing commercial structure when completed. Its lower walls are six feet thick. The walls of Joseph Pulitzer’s World Building (1890) in New York City were 11.5 feet thick in the basement and seven feet thick at street level.

Over the second half of the 19th century, architects and engineers experimented with using iron columns and beams to reduce the amount of masonry, until they finally hit upon the idea of using iron–and later steel–to frame the entire structure, eliminating the need for load-bearing masonry altogether. The discovery of the steel skeleton meant that the gravity barrier, so to speak, had finally been broken. This was truly revolutionary, since from the dawn of civilization, some 10,000 years ago, until the 1880s, all of the world’s tallest structures were held up with stone.

Blowing in the Wind

Once the gravity problem was solved, however, a new problem arose. For a building of about 10 stories or higher, wind forces—the so-called lateral loads—start to increase dramatically (ignoring the problem of earthquakes for now. I will return to this in a future post). No one wants to work in a building that sways; and even more so, no one wants a building that might someday topple over in a hurricane.

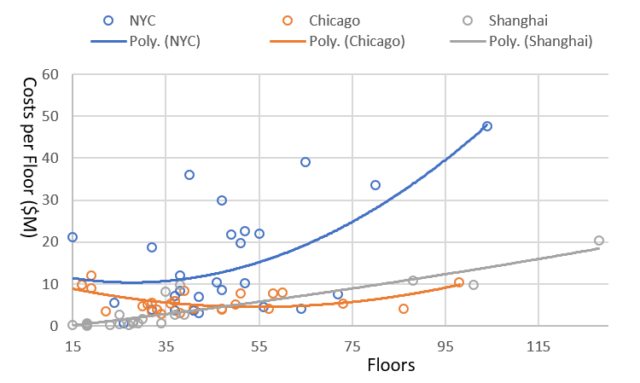

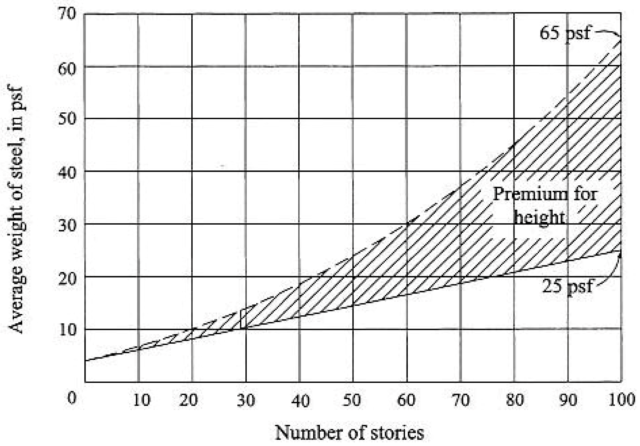

For about 80 years, the solution to the wind problem was, essentially, to use more steel—either thicker and/or more beams and columns, and/or diagonal bracing elements. The problem though is that as a building gets taller, the amount of required steel rises disproportionately. Furthermore, the additional steel columns needed for rigidity meant that the internal space became increasingly crowded for occupants who, over the course of the 20th century, were demanding larger and more open floor plans.

In 1969, the renowned structural engineer, Fazlur Khan of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), estimated the theoretical steel “premium” as building got taller. He demonstrated that if gravity forces were the only concern the amount of steel would need to rise at a relatively slow, linear rate as buildings got taller. But, if the wind problem was factored in, the amount of steel needed would rise at an increasing rate.

A New Hope

In the 1960s, things started to change. Fazlur Khan was one of several engineers who helped trigger a revolution or paradigm shift for engineering tall buildings. His basic argument was that because the braced steel skeleton was inefficient at greater heights, new structural methods were needed to stop the wind. And soon they began to emerge. As the noted SOM engineer, William Baker, writes,

This cloudburst of new systems was made possible by the advent of computers and engineering pioneers such as Fazlur Khan, Hal Iyengar, William LeMessurier, Leslie Robertson and others. Although the conceptual foundations of these systems were straightforward, earlier computational methods were not adequate for use in design. At last, the viability of these systems could be demonstrated by utilizing the mainframe computer. In addition to validating the systems, important parametric studies were done to establish the applicable height range for the various systems.

These new systems allowed for buildings that were not only taller but also were stiffer and used less steel per square foot of building area. The Empire State Building weighed in at 42.2 pounds per square foot, while the much taller Sears (Willis) Tower (1974) was only 33.0 pounds per square foot.

Composite Construction

Besides design innovations, another vital discovery was with materials. No longer are the world’s tallest buildings constructed using only steel. Today, the vast majority of them employ a composite design of both steel and concrete to make an more efficient structure. William Baker writes,

Steel is excellent for framing long span office floors; it is lightweight, can be easily modified by tenants and can be quickly erected. Concrete, on the other hand, is very cost effective in carrying the weight of the tower, and the mass is beneficial in reducing building motions. New formwork systems and the ability to pump concrete to great heights have also greatly increased the speed of concrete construction. In addition, the inherent damping of a concrete lateral system is generally higher than a steel system.

The resulting merger of steel and concrete into composite buildings has resulted in seemingly endless combinations of the two systems. Perhaps the most common composite systems use reinforced concrete cores and steel floor framing.

The Structural Revolution

Engineers have developed many different structural systems to go taller while neutralizing the wind (and other technologies to be discussed in a future post). In fact, one can say that today there is an abundance of possibilities. Builders, in some sense, can take a one-from-column-A-and-one-from-column-B approach depending on local conditions, architectural styles, and the intended occupants. Here, I will briefly highlight a few (but certainly not all) of the vital innovations in structural systems to give a flavor of how the technology has evolved.

The Tube

The first innovation in the modern technological revolution was the tubular design, developed by Fazlur Khan in 1961, and first used in the 43-story DeWitt-Chestnut Apartment Building (1963) in Chicago. With the tube design, the façade is the structure–a vertical tube–where the perimeter columns are placed relatively close to each other and are held together by beams. Thus, the façade performs triple duty: it holds up the structure, it braces it against the wind, and is part of the architectural style. The Twin Towers represent the early mastery of this form.

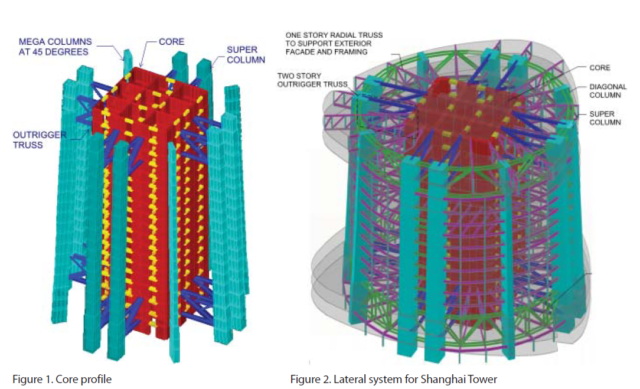

The tube design can be further modified. The tube-in-tube design puts an additional tube in the central core. A braced tube adds extra stiffness with braces that run diagonal to the columns. A bundled tube design puts many tubes together (and each tube can be a different height). This design, also by Fazlur Khan, was used to create the Sears (Willis) Tower (1974) in Chicago.

The Outrigger

Originally, an outrigger was a set of horizontal beams on a sailboat emanating from the ship’s side to add support. The idea for skyscrapers was first used by architect, Luigi Moretti, and his collaborator, engineer, Pierre Luigi Lervi, for the 190-m tall 47-story Place Victoria Building (now the Stock Exchange Tower) in 1964 in Montreal. Recently, it has become one of the most popular designs for supertall structures. In this case, evenly spaced throughout the building are two or three outriggers, which are floor-high “walls” of either concrete or steel trusses that run from the central core to the perimeter. Many of the outrigger buildings also have mega columns—very thick columns—to further stiffen the structure. The 128-story Shanghai Tower (2015) uses this design, as does the 101-story Taipei 101 (2004).

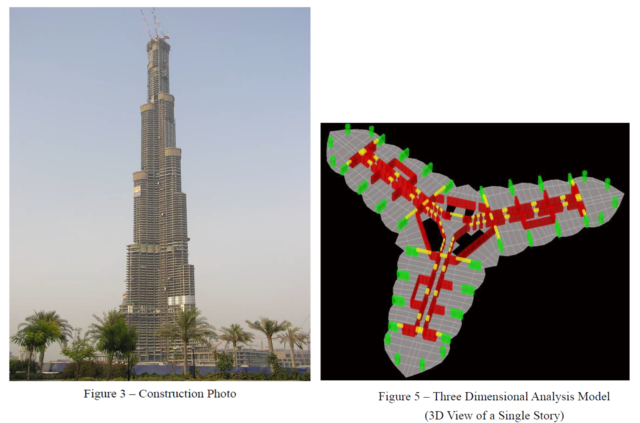

The Buttressed Core

SOM engineer William Baker initiated the idea of buttressed core for supertalls. Originally it was used for the structure of the 73-story Tower Palace Three (2004) in Seoul, though the idea seems to have been first implemented in the CN Tower in Toronto (1976). The success of the design suggested it could be used for an even taller structure, and was eventually chosen as the structural system for the 163-story Burj Khalifa (2010). The key is that the core of the building is shaped like the letter “Y.” The skyscraper has a typical central core, but also has three additional cores attached to it, where each wing “buttresses” the other two. The central core and wings together make the building particularly resistant to the various wind forces. This structural type is also going to be used for the world’s first 1-kilometer skyscraper, the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, which is under construction and will likely be completed in 2020.

Toward the Mile-High Building

Given the feverish pace of skyscraper growth around the world, it’s unlikely that the Jeddah Tower will remain the world’s tallest building for very long. Global competition will drive not only innovations but also the demand for greater heights.

So, what kind of structure might we expect for the first mile-high tower? There is no way, of course, to answer this question. The final design depends on many factors, including architectural style, building use, cost of materials, local building regulations, and environmental and geological conditions. But it is reasonable to say that a mile-high skyscraper will contain a mix of structural elements described above.

Inspiration

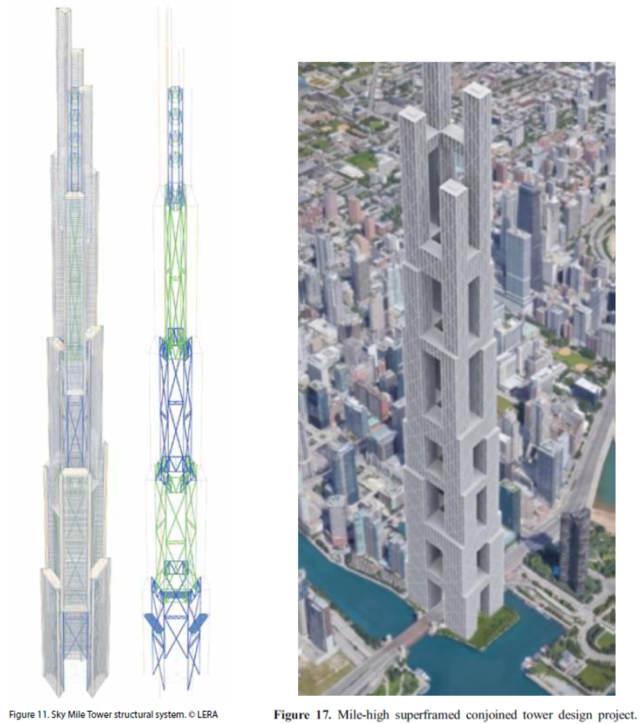

If we want inspiration, we can look to some of the visionary proposals offered in recent years. Here are two that exploit the idea of joining multiple structures to make one larger, stiffer skyscraper. Tokyo’s Sky Mile Tower calls for multiple sets of three building “legs” interconnected to create a hexagon-shaped structure. Each building leg has “megabracing” combined with concrete shear walls along the sides.

Another design is offered by Yale professor Kyoung Sun Moon and his student Chris Huyan. In this design, the mile-high skyscraper is comprised of four braced tube towers. Each tube is interconnected by horizontal braced tubes of multiple stories.

The Skyscraper System

But structural form is only one part of the equation. The successful supertall is a system of many interconnected parts and must employ a host of technologies to provide vital services, including fast movement up and down, safety, and comfort. It is to these we will turn in future posts.

The rest of the series on the technology of tall can be found here.

I would like to thank Maria Thompson for valuable editorial assistance.