Jason M. Barr (@JasonBarrRU) April 19, 2021

Editor’s Note: In the Skynomics Blog, I frequently discuss the subject of housing affordability in New York City. It thus piqued my interest when I learned about a group of New Yorkers who have become politically engaged through their organization, Open New York, to increase the city’s housing stock. This is Part II of a two-part roundtable Q&A with four of their members. Part I is here.

The Panelists

Casey Berkovitz is an Open New York board member and senior associate at The Century Foundation, a public policy organization. He tweets at @caseyberk.

Kyle Dontoh is a board member of Open New York and an independent strategy and transformation consultant. He tweets at @kynakwado.

Amelia Josephson is an Open New York board member and program manager at The Financial Health Network, a nonprofit that unites industries, business leaders, policymakers, innovators, and visionaries in a shared mission to improve financial health for all. She tweets at @JosephsonAmelia.

Will Thomas is the Executive Director of Open New York, an independent, grassroots pro-housing organization fighting for more housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

Roundtable Q&A

JB: People in New York care strongly about preserving the city’s building heritage. How do you think New York can balance the demand for preservation while still providing more housing?

Amelia

New York City has a tremendous architectural heritage, and of course, we have lost some iconic buildings along the way. So, we understand where the desire for historic preservation comes from. The problem we see is that New York City currently has what we consider excessive landmarking in some of the areas that are best served by transit and closest to job centers.

Around 28 percent of Manhattan is landmarked, for example. Historic districts (as opposed to the landmarking of individual buildings) really restrict our ability to build homes and welcome more neighbors to amenity-rich parts of the city, which is why those historic districts tend to be whiter and have much more expensive housing stock.

We’d like to shift priorities to make it easier to build more homes in high-opportunity neighborhoods while also giving greater protection to historic treasures in the outer boroughs that really haven’t gotten much love from the existing historic preservation movement.

Will

Going off of Amelia’s points, I think a distinction has to be made between district landmarking and individual landmarking. To me, individual landmarking seems harder to abuse as exclusionary zoning by another means. You can even craft reforms that would allow these sorts of landmarks to sell their development rights, or “air rights,” more broadly, ensuring that a similar amount of housing is ultimately produced even if the landmarked site isn’t developed itself.

However, declaring whole neighborhoods to be “historic districts”–where current scale and architecture is forever preserved––strikes me as more problematic. I’m sure defenders of these sorts of districts would note that New York’s landmark regime is not at all a blanket ban on new housing––projects in historic districts simply must pass muster with the Landmarks Preservation Commission. But in practice, requiring new housing to go through a somewhat capricious and onerous process surely impedes construction that would otherwise occur. And this is assuming that everyone is acting in good faith to preserve history, which is unfortunately not the case.

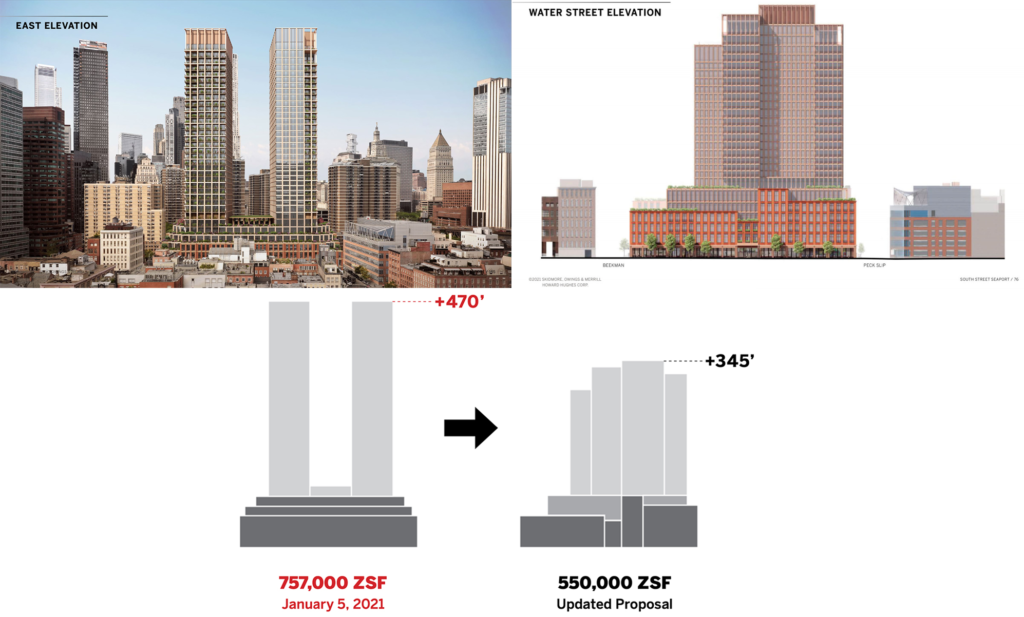

We recently supported a mixed-income housing proposal in a historic district–250 Water Street, in South Street Seaport. The project would not have replaced any historic building, just a parking lot. Importantly, it also would have provided a $50 million lifeline to the Seaport Museum, which is in danger of going out of business.

Unfortunately, the LPC [Landmarks Preservation Commission] deferred to local opposition, who argued that the building would be too tall and dense for the historic district––despite the fact that the district itself would not have existed if not for the efforts of the Museum. In rejecting a project that would save the Museum and further historic preservation, the LPC has revealed that historic districts do not necessarily have preservationist interests at heart.

Kyle

For me, this is an interesting question, as someone whose interest in urbanism ultimately stems from a preservationist impulse. It’s a story a little too convoluted to tell in the space we have here, but I will say that as my understanding of the process of how cities grew and declined matured, the importance of the built form diminished in importance relative to the process through which that built form came about.

This is where I have a problem with New Urbanism, an urbanist framework which I think many in the preservationist community are proponents of, and something I used to be a passionate advocate for. It takes the great traditional communities of the past and tries to replicate their forms without really understanding the process through which those communities came about.

There seems to be a certain idea that if you get the built form right, after a certain point you will be “done,” but this is completely alien to cities as they actually exist. Cities are never “done,” they are a continual work in progress. This is the problem with preservation as it currently exists: it tries to freeze the city in time. This might work on a building-by-building level or even for blocks, but when you try to do this to multiple neighborhoods across the city it becomes untenable.

You can hardly go a day without hearing about Jane Jacobs and Greenwich Village, but the West Village of Jacobs’ day and the one we have now are, built form notwithstanding, are two completely different beasts. In the 1950s, it was an affordable, diverse, mixed income neighborhood that had a wide array of housing types. Today, it’s an ultra-elite ghetto; the buildings have been saved, but the community has been completely transformed.

So we really need to interrogate what exactly we’re trying to preserve: buildings or communities? Because it should by now be clear that, in the dynamic and perpetually changing landscape of a city, in the long-run, it’s all but impossible to do both, especially when, as Amelia said, those neighborhoods you’re preserving are the very same ones which have the best transit connectivity and are adjacent to employment centers. And this is before you broach the issue of landmarking being weaponized for other NIMBY objectives as opposed to actually preserving any building of aesthetic or historical significance.

One of the more eye-opening moments here came during the fight over the 14th Street Tech Hub (now called Zero Irving) when the GVSHP [Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation] demanded that either nearly 200 buildings be landmarked or the surrounding area be downzoned. It was transparently obvious that historic merit was completely orthogonal to what they were demanding: it was solely about preventing development.

JB: What will it take to get buy-in—both from local leaders and residents—for a more market-oriented approach to expanding New York’s middle and low-income housing stock?

Kyle

There’s this conventional wisdom, I think we can say, that solving the affordability crisis will involve some degree of exclusion. Restricting foreign buyers, taxing pied-à-terres or other second homes, trying to slow down development in gentrifying neighborhoods, or by some other means inhibiting change. We, of course, disagree very, very strongly with this conventional wisdom, which has held sway really since the early 1960s, which is when you see permits for new construction rapidly begin to taper off; they’ve never even come close to pre-1961 levels, with the exception of 2015, when 421-a was expiring.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that many, if not most, of the people who adhere to this conventional wisdom regard themselves as progressives who are in all other fields great advocates of inclusion, of welcoming newcomers, of diversity, of tolerance and acceptance of the foreign or the other, but when it comes to the housing crisis, it’s taken for granted that there will need to be some degree of excluding newcomers. Very rarely is this exclusionary impulse openly directed towards, say, immigrants, people of color, or otherwise disadvantaged groups—although it’s apparently okay when directed towards people from, say, Ohio—but the effect is the same. But if you want to have an open, welcoming city, you ultimately need to build one that is physically capable of accommodating newcomers. Or you need to be forthright and pull up the drawbridge. But this status quo, of saying one thing but doing another, is ultimately untenable.

In one of the candidate forums, we held in January, one of our endorsed candidates for City Council, Althea Stevens, running in District 16 in the Bronx, raised an excellent point. It was that this zero-sum framing helps no one; that underprivileged communities of color need—and I would say deserve—new, high-quality housing, more public services, better parks, more restaurants, and more stores. We should be able to provide these communities these amenities, but we should be able to do this without displacing people. Ultimately, the best way to prevent displacement is by ensuring that there are enough homes being provided in high-opportunity neighborhoods rather than people fighting over a shrinking pie, and if we can show that this is possible, we can generate the buy-in needed for a more market-oriented approach.

Casey

I think it’s important, too, to show that our vision of abundant housing is actually different from the status quo of how development has worked in recent decades. There’s understandable suspicion among some communities toward market-driven development, because what that’s looked like under recent mayoral administrations is downzoning white, wealthy neighborhoods, concentrating new development in majority-POC, working class neighborhoods. So it’s natural for people who have seen new amenities and construction as being for “somebody else” to be suspicious when it comes to their neighborhood. (One reason that Open New York only advocates for projects in white, wealthy neighborhoods, by the way.) So we need to make it clear that what we’re advocating for is a city where everybody can benefit from new amenities and new homes, rather than a vicious cycle where neighborhood improvements mean that gentrifiers are on the way to steal your slice of pie.

Will

I think Casey has it exactly right––many people don’t feel like new development is for them, which makes it really hard for them to support new development. Part of the solution here would be legalizing cheaper housing typologies first––ADUs [accessory dwelling unit], SROs [single room occupancy], basement apartments, mid-rises in more suburban areas. But I also think simply pointing to places that build a great deal of housing and see far cheaper prices can also do a lot to convince people that new development doesn’t necessarily have to be for millionaires. In Jersey City, just across the Hudson, I’ve seen brand-new studio apartments––30 minutes to Manhattan by the PATH, with dishwashers and in-unit washer/dryers––leasing for $1,400 a month. We can have that in New York too.

JB: A CurbedNY article on Open New York quoted Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation [GVSHP] as saying, “This small group of pro-development fetishists seems to make no distinctions between good or bad development, or have any recognition of the need for balance and mitigation…I think most New Yorkers agree that simply allowing the barons of real estate to have their way with our neighborhoods and our city, as this group proposes, is not the way to cure our ills or plan for our future.” Your Response?

Casey

The idea that we don’t have preferences for which types of development we support, or that we only serve “big real estate,” is unhinged from the reality of our work, and shows how weak the actual arguments to keep wealthy neighborhoods preserved in amber are. A core part of our mission is that we only advocate for projects in white, wealthy neighborhoods, because that’s where exclusionary interests have been able to lock others out of opportunity, and all of the projects we advocate for have an affordable component.

In addition, parts of the real estate industry oppose our work—the way that some developers, brokers, and realtors ensure a steady profit is by limiting the supply of new homes, and therefore competition. (Some of whom fund Berman’s own organization, I should add.) We’ve seen the fruits of GVSHP’s approach: the Village and nearby neighborhoods are unaffordable to anyone who doesn’t have millions of dollars to spend to buy a brownstone or loft, and our city is among the most segregated cities in the United States. I’m proud that our approach to “cure our ills or plan for our future” has won us allies among fair housing groups, tenant advocates, planning organizations, and progressive politicians from across the city.

Kyle

Well, I suppose I can speak to this question as an open and unrepentant “pro-development fetishist.” I personally like tall buildings, and I don’t understand the kind of person who lives in New York City, literal home of the skyscraper, yet feels the need to complain about shadows or tall buildings being “out of character.” The fact that there are infinitely many other places one could live where they would not have to deal with tall buildings aside all the things that draw people to New York: the jobs, the diverse cultural life, the restaurants, etc., are all downstream of density. The sheer number of people here is what makes this bewildering array of opportunity possible, and as nice as it would be (and it would be nice, at least as far as I am concerned), they can’t all live in 18th- or 19th-century townhouses.

As someone who’s struggled to balance their understanding of land use and exclusionary zoning—and the desire to move away from that paradigm which stems from that understanding—with their very strong aesthetic preferences in favor of traditional architecture. In a perfect world, this would not be a problem, because all new buildings would be designed by Peter Pennoyer, Roman & Williams, Robert Stern, Morris Adjmi, Studio Sofield, and so forth (I would note I am very much an outlier from the group on this). But obviously we don’t live in that world. So at the end of the day, we have to ask what is more important: our subjective aesthetic preferences or giving people a place to live?

Read Part I of the Roundtable Q&A with Open New York here.