Jason M. Barr April 18, 2022

Gotham is haunted by a gg-ghost!! The ghost of Robert Moses that is.

Whenever a large public project is announced, there’s always a kneejerk reaction against it, with the naysayers shouting, “Remember Robert Moses!”

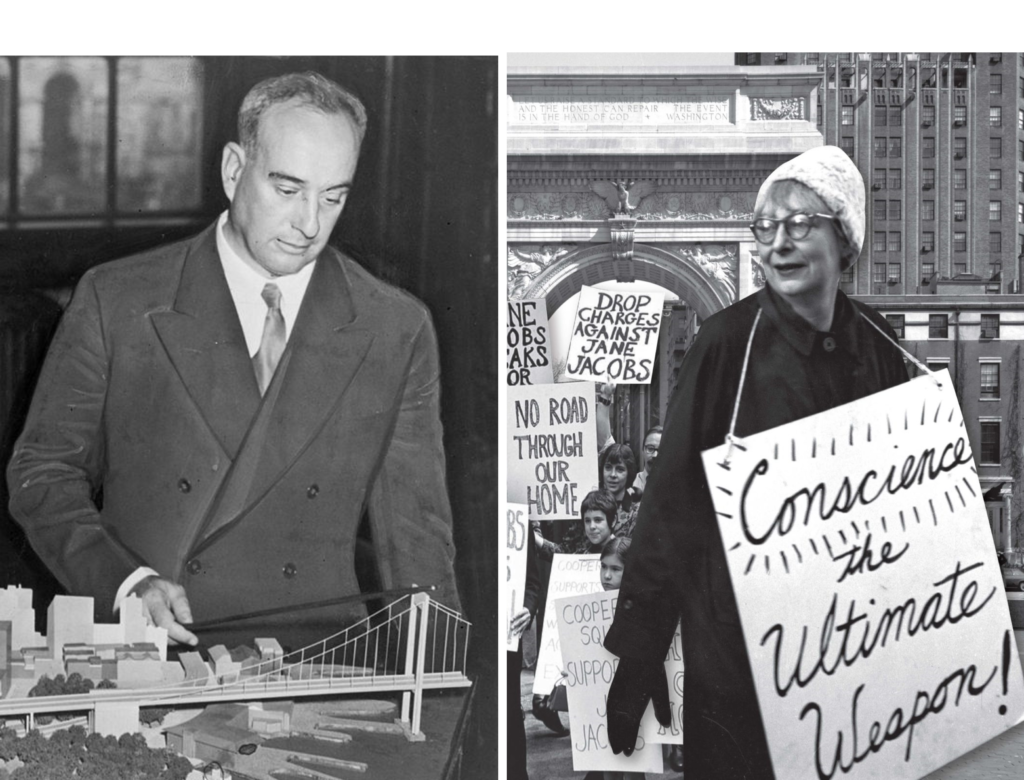

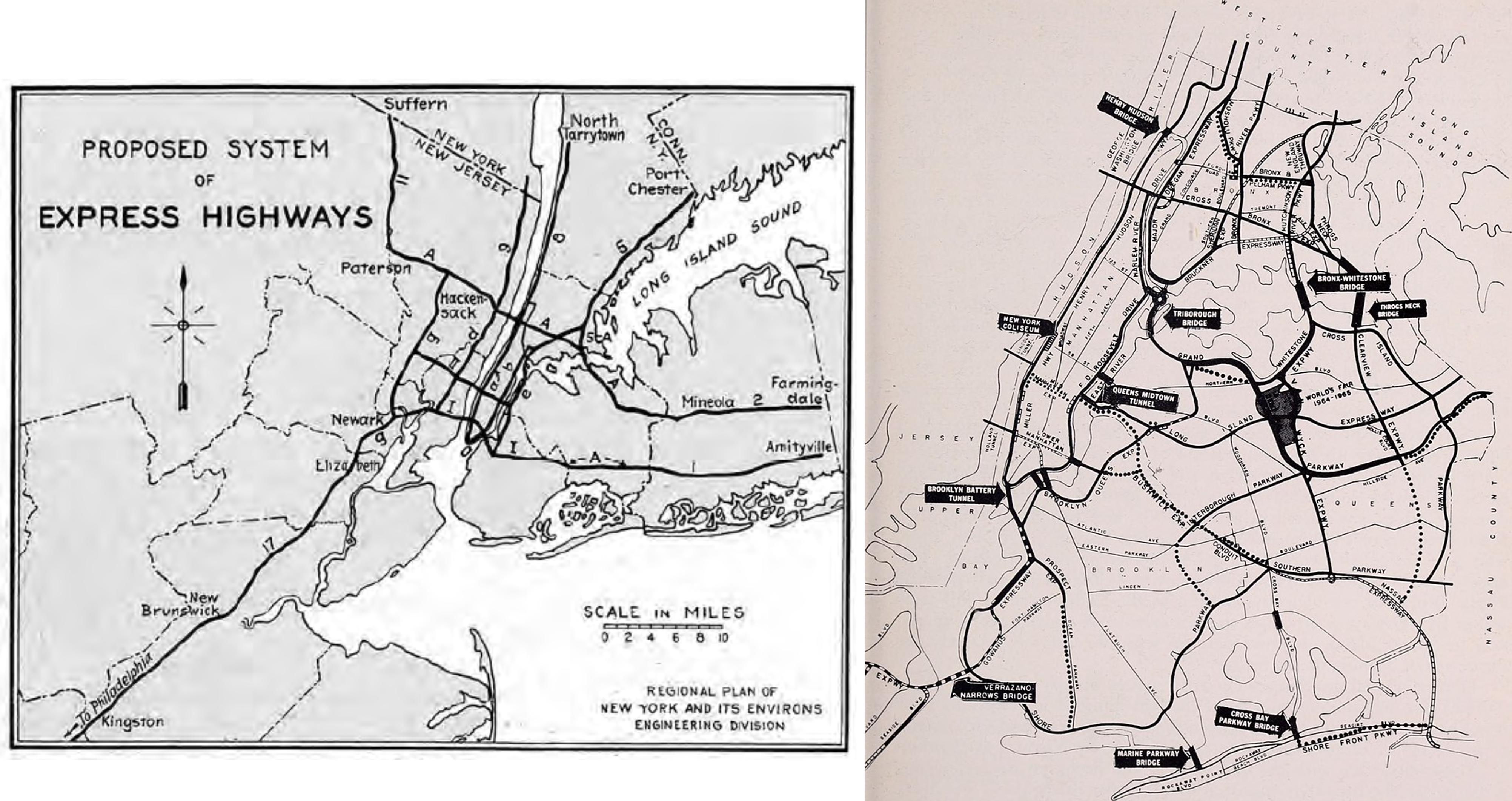

Moses was the Master Builder of New York who, from the Great Depression to the 1960s, oversaw the construction of most of the city’s highways, bridges and tunnels, and slum clearance and public housing projects.

Toward the end of his career, he lost public favor as his plans became increasingly controversial. Then in 1974, Robert Caro published his 1,300-page biography, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. The book is a page-turner, a mix of awe about how Moses could accomplish all that he did and shock about his abuse of power.

Gotham Noir

Caro’s book and Moses’ run-ins with urbanist Jane Jacobs have produced a residual mythology: That his anti-democratic, heavy-handed methods destroyed New York and its bustling neighborhoods, leaving it a worse place as a result (hence the “Fall of New York”).

The story goes that his slum clearance was really people of color clearance. His highways scattered the middle class and left the subway system sinking under its own weight. His building program led to hyper segregation, the hollowing out of the Big Apple, and the destruction of once-vibrant tenement neighborhoods. All the while, his roads were choked with congestion.

His archenemy, who took him down, was none other than the Patron Saint of Good Urbanism, Jane Jacobs. Jacobs argued that Moses and his ilk should leave neighborhoods alone, and let the “slums” unslum themselves naturally. Rather than building highways, the city should invest in good design strategies and user-friendly parks and let diversity do the rest. Density works for the people, not against them.

When Moses wanted to build a highway through her beloved Greenwich Village, things became personal. She led the protests that stopped Moses in his tracks. Good triumphed over evil.

Myth Damage

The myth of Jacobs-cum-David defeating the villainous Moses-cum-Goliath remains pervasive and influences our thinking about urban policies to this day. Both, however, were in their prime during post-World War II New York, when the issues confronting cities and the beliefs about good urbanism were very different.

Their mythification and deification (one for Olympus and the other for Hades) are preventing us from having real debates about the best way forward regarding the problems facing us in the 21st century. The Moses-Jacobs Myth is now harmful. It’s time to move on.

The Legacies of Jacobs and Moses

One cannot underestimate the legacy of Jane Jacobs. Her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is a classic that has inspired countless urbanists. It makes a seductive argument that vibrant urban neighborhoods can magically spring to life if we simply focus on allowing people to find each other and go about their daily lives without much hindrance from the state.

Over time, however, her ideas have transmogrified. In the name of preserving neighborhoods from the wrecking ball or banning the construction of luxury high-rises, residents have used her words to prevent urban re-development. The Gospel of Saint Jane has become the rallying cry of the Nimbyist. Greenwich Village, for example, has become preserved in amber. In 1969, thanks in large part to Jacobs, it was designated as a historic district, and none of its buildings can be torn down.

The result: the bohemians, artists, factory workers, and immigrants who once made it so special can no longer afford to live there. Jacobs’ leave-it-alone philosophy has turned Greenwich Village into an urban country club for those who can afford to pay the membership fee.

Resurrecting Moses

Simultaneously, there have been attempts in the last twenty years or so to revive Moses’ legacy by putting his actions into a larger context. While not condoning his anti-democratic and elitist behavior, “apologists” acknowledge his vast portfolio of accomplishments and note that he was not omnipotent, having been defeated many times throughout his long career, even before Jacobs was on the scene. When compared to “building czars” in other industrial cities, like Chicago, Boston, Detroit, and Newark, his projects were not all that different.

Nonetheless, it’s clear that in the public consciousness, Moses is still the villain, and Jacobs is the hero. He is an example par excellence of big government gone awry. On the other hand, Jacobs is the urbanist of the people, who taught that government can’t and shouldn’t be trusted.

Welcome to the 21st Century

But it’s time we take a step back and put Moses and Jacob in a historical context. They were both fighting over their version of the 20th-century city. Moses was trying to eradicate the old city in the name of progress. Jacobs was trying to preserve the old city in the name of progress. In some sense, both visions were correct.

The automobile was a technological tour de force that had to be dealt with. To ignore the car in post-World War II planning was impossible. But the density so hated by early and mid-20th century reformers is now celebrated. Our thinking about density is the opposite of what it was in 1960.

In this sense, Jacobs won the debate. A whole body of literature in economics has measured the value of “agglomeration.” It shows that density can generate higher incomes, a more diverse economy, and easier access to goods and services.

But we can’t simply say, “get government out of the way so that we can get on with our lives.” The world we live in is very different than theirs, and we are facing a host of issues that they could never have imagined.

End of the Extensive Margin

In 1950, when Moses started building out the highway system in New York, about 74% of the population in New York and immediate counties lived inside the city boundaries.[1] The suburbs were ripe for development. By 1980, only 56% of this population resided in the city. Moses’ program allowed the city’s territory and economy to expand.

But Moses was out of power by 1970, and road construction stopped. Today, the highway system is virtually identical to the one that existed when he retired. Additionally, as the suburbs filled in, towns and villages used their power over zoning to restrict what could be built. These towns have erected virtual moats or walls around the big city. Thus, by circa 1980, the New York City region became de facto “closed.”

When Jacobs was writing, people were fleeing the city, as it was in rough shape from years of decay and deindustrialization. Jacobs tried to stop planners from encouraging (or requiring) urban flight. But even if neighborhoods like Greenwich Village and East Harlem remained vibrant for the working classes, the middle classes wanted to live in the suburbs. Rising incomes and highways allowed them a castle of their own.

But the debate about in-fill versus expansion became moot forty years ago. Expansion stopped because people wanted it stopped. They wanted to circle the wagons and preserve what they had. The suburban homeowners wanted to protect the value of their houses and keep out “the other.” The urbanists wanted to preserve their neighborhoods from the wrecking ball or change more broadly. And the city and state had no will to improve mass transit or make driving more expensive.

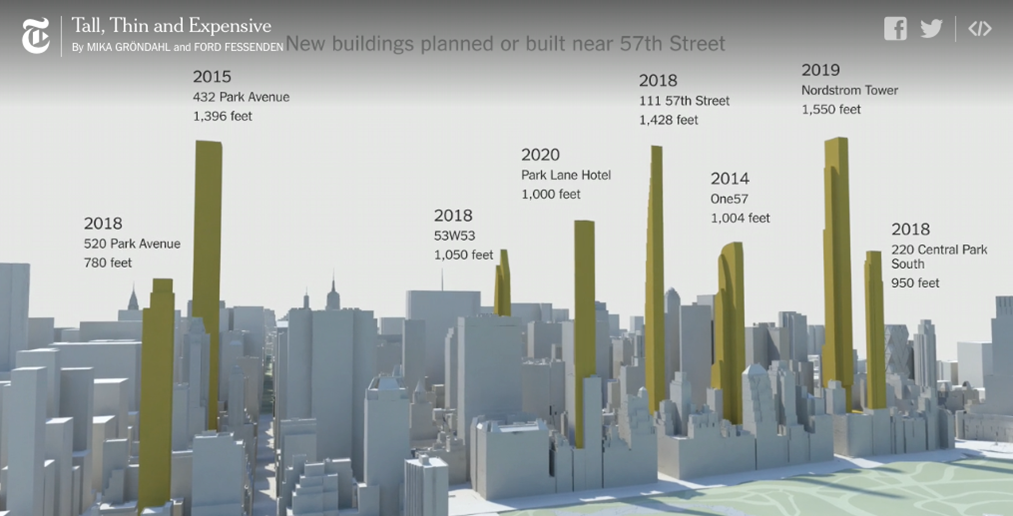

Today, the city can’t expand outward because zoning and transportation limits won’t allow it. The necessary densification within the city is difficult because residents won’t allow it.

The New York Renaissance

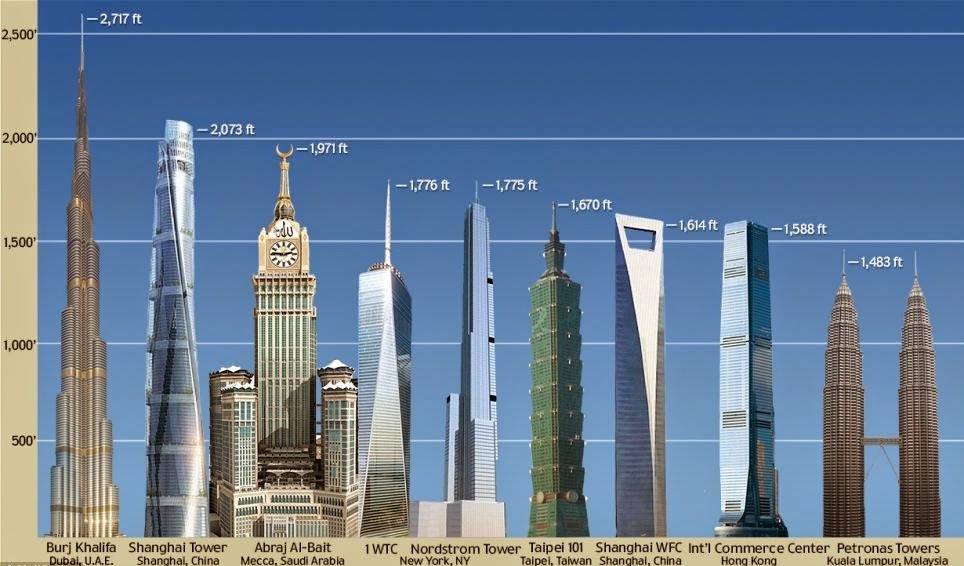

While New York City has always been home to immigrants and a part of the global network of trade, commerce, and finance, today, globalization has radically changed the nature of cities. In 1960, the world population was three billion, and today it is nearly 7.8 billion. Over the same period, per capita income grew by 67%. Thus, world income has grown faster than the world population. That’s a lot of disposable income.

Thanks to technological improvements and growth in productivity, the global population is more mobile, richer, and interconnected than ever before. Correspondingly, there has been a massive change in the nature of work, and we are increasingly dependent on computers and computer networks. In 1960, when Moses and Jacobs were duking it out, there was no such thing as personal computers; music was still enjoyed exclusively on vinyl records, and people read the daily news on printed paper.

Our economic, technological, and sociological changes have profoundly impacted New York City in the 21st century. First is that its importance in the global economy has increased. New forms of work and production are taking place in big cities, be it software and computer tech, finance (and fin-tech), biotech and healthcare, and the supporting system of universities, banks and venture capitalists, business services, and so on. In 1960, one out of every four employed New Yorkers worked in manufacturing, but today that number is 2% (and much of that is probably artisanal foods and craft beers).

Funtown

Second, New York is a haven for fun and consumerism for locals and tourists alike. With greater mobility comes greater engagement with the city. In 1991, New York had about 23 million visitors. In 2019, it was up to 66 million.

Besides the day and week trippers are those who pour in for a year or two or three. It’s reasonable to say that New York is experiencing gentrification on a scale unimagined by Jane Jacobs. Her aim was the deslumming of the tenements, not turning central city neighborhoods into hot spots for the global elite and their offspring. As international money has poured in and the workforce has expanded, the city has been unable to build housing fast enough to accommodate this demand.

While housing costs were always high in New York City, the current housing affordability problem is a historical anomaly. Housing was relatively affordable in the decades after the War because the central city was emptying out while new housing was being built along the suburban fringes (in addition to strict rent controls, but which likely did lots of harm in the big scheme of things). There was plenty of supply to go around.

But the larger point is that the city’s economic resurgence is taking place in a “closed” city, generating higher housing prices, greater income inequality, and massive traffic congestion. These were not issues facing urban America in 1960.

Climate Change

There’s little need to dwell here on climate change beyond saying that rising sea levels and damage from more frequent and devastating storms and surges were a non-issue in 1960. While environmentalism was gaining traction, there was virtually no notion of climate change being a major force. So, the Moses-Jacob debate is silent on this point.

Policies

If residents of the past had the same attitude about infrastructure and public works as today, we’d never have gotten Central Park, the subway system, or any number of the great projects that made New York what it is. Big problems require major government investments and wholescale changes in housing and transportation policies. There is no way around this.

We cannot build a seawall in the harbor and claim that the city is protected from climate change. We cannot upzone a handful of neighborhoods (while also downzoning other ones), give developers tax breaks, and claim we are doing something about housing affordability. We cannot build a Brooklyn-Queens express rail and say we’ve solved the city’s transportation woes.

Making neighborhoods function better means more housing everywhere, greater geographic mobility for all, and sufficient protections against climate changes regionwide. Since a city is inherently an interconnected system of systems, we must recognize that changes in one area inherently affect the others.

The government needs to take steps to move New York into the 21st century. Ideally, these steps should be regional, as the New York metro area is a megacity of 20 million people. But given the municipal fragmentation and the bitterness of the debate, Gotham must take the lead. So here, I propose a broad agenda to get things started.

Restore Trust in Government

We need to restore trust in our government. The first thing is for politicians to recognize that the Depression and Post-War era policies had mixed results. Some produced a better Gotham, and others made it worse. But these policies have generated a vast database of knowledge about what works and what doesn’t. These lessons can be applied to the present. Additionally, we have a mountain of science and social science research that has emerged in the last 50 years that can be applied to the looming crises.

Politicians need to admit that past mistakes engendered mistrust. And they need to restore trust by being open and listening to residents’ input while being honest and direct about the necessary large-scale changes. All this begins with leadership.

Government policies need to create open, transparent, and fair mechanisms that ensure that people harmed by changes are compensated and made whole. To get buy in, all policies must come with a carrot and stick, and they must help reduce the anxiety of change. Policies must be seen as not targeting only one community or neighborhood.

A Master Plan

Along with building trust is the need for a new master plan, not one that tries to tame or control the city, but one that lays out the mechanisms by which neighborhoods will get needed housing, services, and infrastructure upgrades.

What does the plan include?

Transportation

First, it must make driving more expensive. Too many cars choke up the highways and streets and take up too much space for parking. An automobile-oriented lifestyle encourages sprawl and discourages the use of more efficient (and environmentally friendly) mass transit. The way to do this is to set congestion pricing on all the highways, bridges and tunnels, and parking meters. Let the cost of driving reflect the harm it imposes. When the streets and highways are flooded with cars, jack up the prices. Encourage people to use alternate forms of transportation or wait till the roads are under-utilized.

Second, once we can cut down on the number of cars, you can devote significant street usage to mass transit, be it dedicated bus lanes or streetcars. With fewer cars on the streets, more people will take up biking or electric scootering.

Housing

Improvements in transportation without encouraging more housing will only wind up making housing prices more expensive in places that become more accessible. We need a wholesale rethinking of our current zoning rules and affordable housing policies. The key to housing is to let the market decide how much housing is demanded in a neighborhood.

Land values are the best indicator of demand, and when land values rise, it means more people want to live in that neighborhood than are being accommodated. When housing construction is truly able to follow increases in land prices, all neighborhoods, not just central city gentrifying ones, will get their fair share of construction. This new construction will help keep prices in check. But housing markets must be much more fluid for this to happen.

Climate Change

Currently, the city is trying to sneak its way to resiliency—an expansion of the shoreline here, a resuscitation of wetlands there, fixing drainage pipes over there, and so on. But the truth is the problems caused by sea-level rise and more damaging storms and surges cannot be fixed with a few tweaks. The city needs to create a citywide mitigation plan that prepares Gotham for the 21st century and that also considers that climate change damages will make housing more unaffordable, either from lost units along the shorelines or from the costs of mitigation born by property owners.

The city is not using systematic planning now. For example, plans are afoot to build a seawall in New York Bay to protect against surges. During torrential storms, the sewage and rainwater pipes hit capacity forcing waste into the city’s waters. We can imagine a scenario during a hurricane where the seawall is raised and sewage pours into the harbor simultaneously, turning it into a giant toilet bowl. So, surges and storms impact the city in both vertical and horizontal directions at the same time.

The Future

New York has always managed to survive in the face of adversity. It is an economic engine, a home for immigrants, and a cultural dynamo. There’s every reason to believe that it will power its way to the future.

But ultimately, the question we must ask ourselves is: Don’t we prefer a city that works better for everyone rather than one that descends into tribalism and dysfunction? The policy answers to a better city are there. But the social and political will remain a stumbling block.

The myths we tell ourselves are powerful tools that can propel or block us. Thus, the first step forward is to abandon the tiresome tales of old that keep us locked in the past. Let’s develop a new set of stories about the resurrection of Gotham–one about how its residents came together to collectively slay the beasts that were harming its people, and how the city triumphed in the 21st century.

Thanks to Julia Sinitsky for her editorial assistance.

—

[1] In New York, these countries are Nassau and Westchester, and in New Jersey are Hudson, Essex, Middlesex, and Bergen.