Jason M. Barr October 29, 2024

Let’s travel back a century—to New York during the Roaring Twenties.

On our journey, we will see a very different Gotham–not just flappers, speakeasys, and the new jazz–but more importantly massive housing construction. Arguably, 1921 to 1929 was the greatest housing boom in New York’s history. Units of all kinds—high-rises, garden apartments, and one- and two-family homes—were constructed in neighborhoods far and wide. It was a time of housing plenty.

On the other hand, today is a time of housing scarcity, with the housing vacancy rate at a mere 1.4% and with rents constantly rising.

The vital lesson from the Roaring Twenties is that supply matters. When new construction is robust and housing abundant, many benefits follow. First, rents fall. Second, there are more choices, so residents can find the housing size and location that best fits their needs—and they get more space for each rental dollar. Third, new construction upgrades housing quality, allowing households to live in safer, more user-friendly units.[1]

On the other hand, when housing is scarce, rents rise, and residents are forced to accept units that don’t match their needs. And they find it difficult to move when their life circumstances change because they have fewer options.

Housing Supply Then and Now

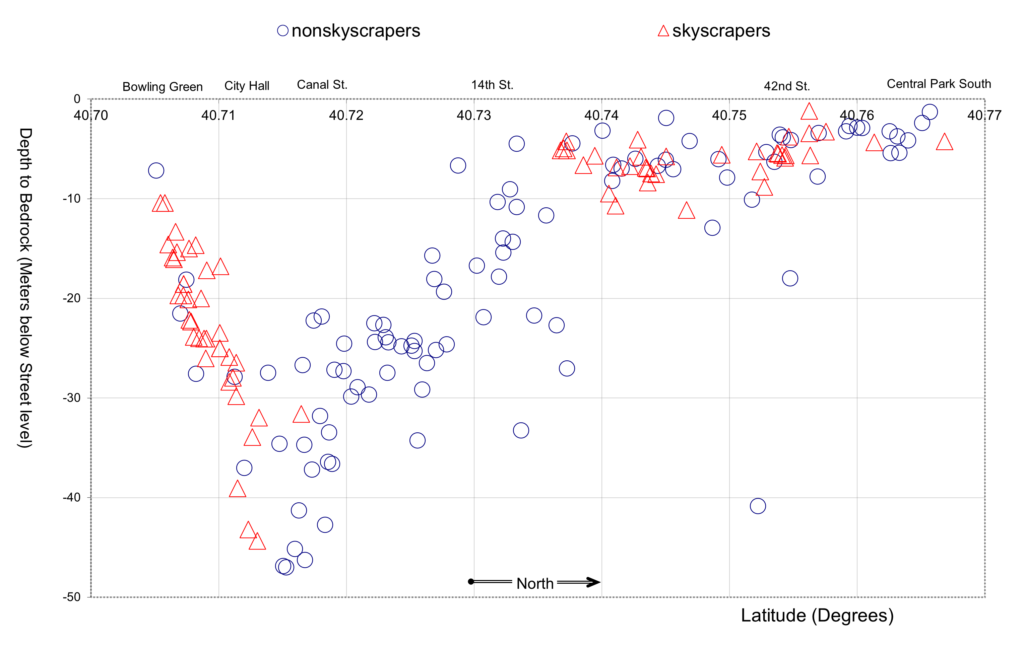

Let’s view the number of units completed in two respective 24-year periods, 1920-1943 and 2000-2023 (see the graph below). Several things jump out. First, the Roaring Twenties was roaring indeed. From 1920 to 1929, New York built over 740,000 housing units (when New York’s population was one-third less than today!). On the other hand, from 2000 to 2009—during the great housing “boom” of the early 2000s—New York built less than 200,000 units. (Data sources can be found here.)

In the 1920s, Gotham was building housing faster than its population growth. Today, the city barely builds, and population growth is a trickle. In the 1920s, when immigrants arrived, they found affordable housing and raised their children in the city. Today, housing is a game of musical chairs. People move in, bid up the price of scarce units, and others leave as a result. The only reason that New York’s population has grown in the 21st century is because of improved health—people are living longer; on the hand, net migration has consistently been negative. That is, year after year, more people leave then arrive.

The second fact that jumps out from the graph is that the period from the Great Depression to America’s entry into World War II (1930 to 1941)—arguably the 12 worst years in American economic history—surpassed housing construction in the best 12 years of the 21st century (2012 to 2023), with 279,134 units during the first period and 239,910 during the second. In short, New York’s 21st-century booms can’t compete with 20th-century depressions.

Vacancy

At the end of 1928, apartment rental vacancy was 7.8%, and nearly half the city’s vacant units were in the lowest-income rentals. Due to subway expansion and brisk housing construction, those with lower incomes could improve their housing situations relatively easily. From 1920 to 1929, Brooklyn alone built 250,000 units—more than all five boroughs from 2000 to 2009.

New York’s current low vacancy rate stems from the slowdown in construction due to the COVID pandemic, high interest rates, the rescinding of 421a tax abatements in 2022, and the renewed growth in the city’s economy. But the truth is that housing vacancy has been unhealthy for many decades. The Rent Stabilization Law defines a “housing emergency” when vacancy is less than 5%. By this definition, the city has continually been in a (self-imposed) housing emergency since World War II and has forgotten what a healthy housing market looks like.

But just as important, nearly all the city’s vacant units are at the high end of the spectrum. Vacancy rates for the lowest-income New Yorkers are way below 1%. With this rate, people have few, if any, opportunities to change or improve their housing.

In With the New Out with the Old

As a bonus, new housing improves health and safety and creates a better match between what residents want and what’s available—tenants get new features and layouts that reflect their current needs and tastes. New housing is generally safer as it incorporates the most current building codes and health standards.[2] As the COVID pandemic has shown, many older buildings, with sealed windows and reliance on air conditioning, were not ideally suited for providing air circulation and outdoor space.

During the 1920s, low-income tenements were abandoned in droves. Officials relished the disappearance of the city’s worst housing. In a report written in 1928 by the New York State Board of Housing—not a group known for its support of tenement landlords—wrote:

Perhaps the most gratifying aspect of the improvement in available dwelling space is the increase in the number of vacancies in the old law tenements and the cheapest apartments generally. The prolonged period of prosperity, combined with the increased physical supply of housing, has made it possible to abandon some of the most unsuitable housing….In this connection, the significant fact is not that the poorer classes of the population now have greater freedom of movement and wider choice—for at best the choice of the lower rental offers very little—but rather that the economic position of at least a portion of the poor has been raised sufficiently to enable them to abandon so large a number of wholly inadequate apartments.

Scarce Housing Policy

On the other hand, today’s “scarce housing policy” causes low-income housing to deteriorate. The problem has been made worse by fiat. In 2019, the De Blasio administration enacted a law limiting landlords’ ability to pass along to tenants the cost of upgrades and improvements. As a result, landlords have been incentivized to worsen the housing stock. Tenants are now squeezed on two ends. They have little choice but to remain in their units because of low vacancy rates, and landlords have little choice but to undermaintain their buildings.

The most recent survey of New York’s housing stock shows a general deterioration in low-income housing in the last few years, which is no doubt tied to both the city’s low vacancy and the 2019 law. As the report states,

The 2023 [NYC Housing Vacancy Survey (NYCHVS)] showed a higher prevalence of most individual housing problems relative to earlier cycles, following the same general pattern as in 2021. This was true for housing types, including rent stabilized units and market rentals. The share of units reporting cracks or holes, broken plaster or peeling paint, and toilet breakdowns remained statistically similar to 2021.

Rents and Affordability

Arguably, the best measure of affordability is rent relative to income. Getting exact apples-to-apples data for the two periods is tricky, but we can generate relatively comparable measures. For the 1920s, I have compiled an index that tracks the average wages of industrial workers in New York to average apartment rents. For rents, I used two indexes. The first was created by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The second is based on newly created data from four economists, Ronan Lyons, Allison Shertzer, Rowena Gray, and David Agorastos.

The BLS data tracks people who have been renting their units for some time. These people are more likely to experience fewer swings in their rent. During the bad years after WWI, rents rose less slowly (in part due to rent control laws and the fact that landlords were often reluctant to dramatically increase rents on longtime tenants). But during the good years, they reduced rents less quickly due to inertia.

On the other hand, the Lyons et al. index comes from asking rents in classified ads from historical newspapers, which reflect the most current market conditions. Spikes are likely to be greater in lean times, when inventory is scarce, and rent drops faster in flush times when housing is abundant.

Rising Rents is Not a Given

When we compare rent indexes to wages, we see that the 1920s was a period of affordability improvement. In 1914, the index values were at 100; by 1928, both indexes were well below that. Viewing the housing scene from today shows the opposite pattern. Tracking median household incomes to median rents shows that they have consistently risen in the 21st century. Researchers and policymakers consider housing “affordable” when it can be provided at 30% or less of household income. Since 2000, the median rent-to-income ratio has been consistently above 30%. And rents relative income has dramatically risen to above 50% for the lowest-income New Yorkers. The city’s scarce housing is, in effect, impoverishing a large swath of residents.

What’s the Difference?

Of course, the real estate market in the Roaring Twenties was different from today. First was that the zoning codes were relatively lax. Experts in the mid-20th century estimated that if the city were built out according to the zoning (and tenement housing) codes enacted in 1916, the city would hold somewhere between 55 and 77 million people!

In 1961, the city was strongly downzoned. By my estimate, the zoning codes today allow for a maximum population of about 12 million people, though this likely overstates the case because 60% of residential properties are either above their maximum allowable floor area limit or within 25% of it. These are properties that are illegal or economically unfeasible to densify.

Second, there was no rent control or rent stabilization law as we know them. There was a form of rent limits implemented in 1920 during the “famine” years following World War I, but they did not inhibit new construction when the timing was right. Today, landlords cannot legally evict tenants in rent-stabilized buildings, and who have no incentive (or ability) to move because there nowhere to go.

Third, the amount of land for development was much greater back then. By 1980 or so, most of the large pockets of residential undeveloped land had been filled in. In the Roaring Twenties, large swaths of land were still open for urban development, and developers were buying up these lots to erect large apartment buildings or entire neighborhoods. While Gotham still has a trove of underutilized land, converting it to more housing is difficult and expensive because of the inability to remove tenants from a building, the fragmented nature of lot ownership, and stringent zoning regulations.

Lessons for Today

The key lesson for today, however, is that when a city builds housing faster than its population particularly in the outer areas, prices drop or flatten, quality improves, and residents have more choices. If a city builds large quantities of middle-income housing, it frees up older units for lower-income residents (through filtering), and they get better housing than otherwise.

Unlike the Roaring Twenties, however, the New York faces the need to redevelop and densify in a built-up city. I have written widely on what the New York can do to fix this problem but let me itemize a few key steps.

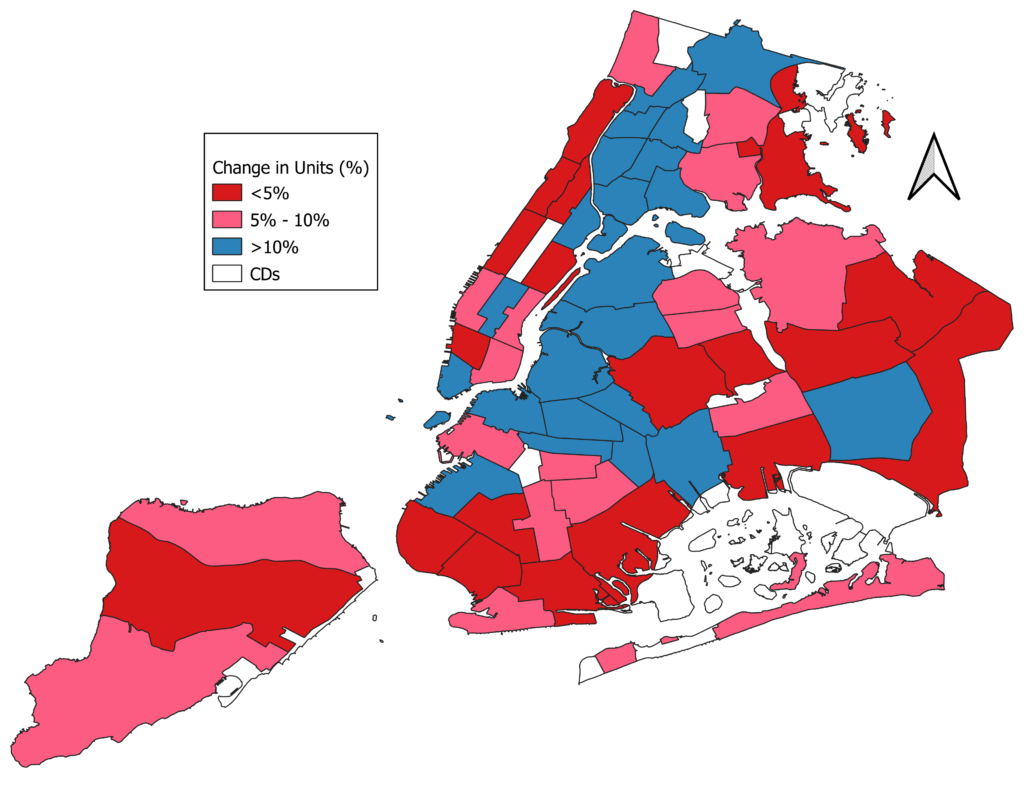

Transit Oriented Development

First is to encourage transit-oriented development by the subway lines outside of Manhattan. Upzone these areas for mid-rise buildings. 92% of housing near subway stops outside of Manhattan is three stories or less. If each building was redeveloped by adding double the current stories (and units)—that is, from two to four, or three to six, the affordable housing crisis would be over.

Target Vacancy Rates

Second, city government needs to target neighborhood vacancy rates. One strategy is for the City to buy large, under-utilized lots and sell off the ground leases to developers for new middle-income housing. As the vacancy rates go above 5%, tenants will have more flexibility and choices, and developers will be freer to redevelop their properties to contain more housing.

Reduce Construction Costs

Third, the government also needs to reduce regulations that choke off the building of affordable housing; and it must offer construction subsidies to lower the high construction costs, with proportionally higher subsidies for buildings that will rent to those with moderate and lower incomes.

Plan for Growth

Lastly, the City must plan for growth. As neighborhoods add more residents, the government needs to be ready to invest in better transportation—like streetcar service, dedicated bus lanes, and more subway lines—and to add more schools, services, and parks to preserve the quality of life.

City of Yes?

To his credit, Mayor Eric Adams is promoting re-writing the zoning rules to allow for more housing across the city through his City of Yes Housing Opportunity program. However, even if fully passed by the city council, which seems doubtful, the program would only generate about 7,000 additional units per year–hardly enough to make a dent in the problem.

If New York really wants to make housing affordable it needs a new Roaring Twenties for the 21st century–there’s still time to get started!

—

[1] This is not to deny the charm of older buildings, but the key is for a city to find a better balance between preservation and accommodating the needs of the present.

[2] Having said this, building codes often create an undue burden for those constructing low-income housing. If regulations were reasonably pared back, low-income housing would be cheaper to build.