Jason M. Barr (@JasonBarrRU) May 11, 2021

Author’s note: This post is Part I of a four-part series on the birth and growth of modern zoning, focusing on the planning tool the Floor Area Ratio (FAR). Part I is about the birth of the FAR in the 1920s. Part II will be about how the FAR was formalized and popularized during the Great Depression. Following that, Part III will cover how the FAR came to be adopted citywide in the 1961 New York City Zoning Resolution. Finally, Part IV will discuss how FAR regulations spread to the rest of the world. My three-part series on the 1916 New York Zoning Resolution can be read here.

Preface

Welcome to FARtopia—a magical place—where housing is unaffordable for most of the population, and any suggestion of knocking down an older building to replace it with a taller one is met with swift and fierce shaming; where the status quo is king, and any change that might make life better for its people is instantly vetoed; where the residents live by their motto: ne in terram meam.

How did such a fantastic place come to be? Take my hand and join me on a journey to see how it all began.

The Floor Area Ratio

Today, one of the main ways that cities measure density is through the floor area ratio (FAR)—which tells how much building space is provided per square foot or meter of land. A 10-story building covering the whole lot will have an FAR of approximately ten. A 20-story building covering half the lot will also have an FAR of about ten.[1]

Ten is a big number in FARtopia. Most residential neighborhoods in the United States have FARs of one or less—the de facto standard for a single-family dwelling with two stories. The entire city of New York has a residential FAR of only 1.2. Even hyper-dense Manhattan has a residential FAR of only four.[2]

Fighting Fire with FAR

Cities around the world regulate density by capping the maximum allowable FAR for new construction. By design, planners calculated the FARs of older buildings and then shaved off a few “FAR points” to reduce the bulk of new ones. In this way, they permit taller buildings in the center but also lock in low-density suburbia.

In midtown Manhattan, for example, the maximum allowable residential FAR is 10. With this fixed value, a developer can build a medium-rise building that takes up most of the lot or a tall building with a very small footprint–and both would have the same total floor area. Thus, extra height must also come with more open space. This is the inherent trade-off that developers face when deciding how tall to build–short and squat, tall and narrow, or somewhere in between.

NIMBY v. YIMBY

The seemingly dry and technical concept of the floor area ratio is vital for understanding both the quality of urban life and the cost of housing. FAR caps are a large part of why new construction is so controversial. When economic realities bump up against the city-created caps, and it is profitable for new construction to go beyond the established limits, developers must get special permission from the city. This triggers a fight between the NIMBYists and the YIMBYists and the battle for the “soul of the city” is fought once again in a real estate version of the movie, Groundhog Day.

FAR caps are also the reason why it is illegal on more than 50% of New York City soil for a landowner to build anything except a one- or two-family home. Have an empty garage that you want to convert to an apartment, or want to add a floor to your house? You cannot do it, as it can bring you above your allowable FAR. By limiting building density, these caps help produce urban sprawl, traffic congestion, higher carbon footprints, and more expensive housing.

FAR caps also means that New Yorkers can peddle “air.” If a plot owner has unused allowable floor area on her property, she can sell it to a neighbor, who can then build even taller. In Manhattan’s tight market, air sells for millions of dollars, and it helps explain the rise of the superslim towers south of Central Park. In short, by capping FARs, the city makes development rights a scarce resource, prompting developers to undertake strategic actions to game this city-produced scarcity.

The Birth of FAR

Wide-scale use of FAR regulations began in Chicago in 1957.[3] They were implemented in New York in 1961 and spread from there.[4] Although New York is often given credit for the invention of the FAR concept in 1961, the idea had been “in the air” for at least half a century, and its popularity was a result of British planners.

The origins of the FAR can be traced back to a group of thinkers who aimed to transform 20th-century cities into their version of utopia. A review of this history also suggests that today FAR caps are the planning equivalent of the 8-track tape or the Commodore 64 personal computer.

The FAR idea sprung from specific convictions about cities. First, all cities needed to look and feel suburban, and second, private developers could not be trusted to provide the right kinds of housing in the right locations. For this reason, private property must be eliminated, or at least land owners must be thoroughly tamed in a way that creates micromanaged order.

The envisioned utopia for the working classes looked a lot like middle-class Victorian suburbs, and this thinking directly led to attempts to engineer New York in that image. Its proponents experimented with small real estate ventures in the 1920s and then moved to government-promoted slum clearance and public housing during the Great Depression.

The 1961 zoning codes emerged from a firm belief that urban density was an evil and the means to utopia was to eliminate it. It does not matter that in the 21st century, these beliefs have fallen by the wayside from the perspective of residents, urbanists, and planners alike. But the city still clings to its vision of FARtopia.[5]

One lesson from a review of this history is that, as author (and utopianist) Lewis Mumford concluded, “life is better than utopia.” And perhaps, by extension, utopia cannot be mandated from above.[6]

Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City

The story begins with writer and visionary Ebenezer Howard, who was born in London in 1850. At 21, he moved to the U.S. for a short spell. However, by 1876, he was back in London, working as a court reporter with Hansard, which produces the official record of Parliament.

Howard became interested in the problem of cities and poverty. He was preoccupied, as were many in his day, with the ills of the slums. The poor were forced off their farms and packed like cattle into overcrowded tenements and, if lucky enough to find work, were paid a miserable, exploitative wage. The poor had neither the benefits of urban life nor the fresh air of nature. Influenced by utopian thinkers, he set down to create his own version of heaven-on-earth, which he called Garden City. As documented in his book, Garden Cities of To-morrow, his idea was to build a planned city in the agricultural hinterland, where greenery abounded.[7]

Neither socialist nor radical agitator, he aimed to promote better living through cooperative or limited dividend real estate investments. He believed cheap land, combined with the efficient arrangement of buildings and infrastructure, would allow for both profit and a small slice of utopia away from the soul-crushing juggernaut that was London.

The Plan

Garden City forms when a group of investors purchases 6,000 acres (9.4 miles2, 28.3 km2) of land. One thousand acres (4 km2) are reserved for the town, and the rest for open and agricultural areas. Once built out, Garden City holds exactly 32,000 residents, along with their homes and the factories in which they work.

Garden City is arranged in a very specific manner to promote not only healthy living but also industrial efficiency. Garden City is arranged in a series of concentric circles or rings. The inner circle is for a park. The next ring is for a “crystal palace,” where the residents do their shopping. The next layer is for homes, mostly free-standing single-family structures with small gardens. After that are the factories. Beyond them is the greenbelt. Railroads and street layouts promote the fluid movement of people and goods.

When Garden City hits its maximum population, it spawns a new sister city on the other side of the greenbelt. In this way, over time, Garden City replicates itself in a fractal formation of a circle of circular cities—eventually taking on a Victorian resemblance to Sir Thomas More’s island of Utopia.

The Disciples of Howard

Howard inspired the construction of several Garden Cities. The first was that of Letchworth, 34 miles (54 km) north of London, which began in 1903. The second was Hampstead Garden Suburb within Greater London, created in 1907. Both were co-designed by Raymond Unwin.

Unwin was born in Yorkshire in 1863 but grew up in Oxford. In 1885, he moved to Manchester to be the secretary of William Morris’ local Socialist League. Unwin developed an interest in planning, and in 1903 helped launch the first Garden City experiment. Over the ensuing decades, he became a highly influential and decorated planner. Later, he would move to the United States and help spread the gospel. In the 1930s, he was a visiting professor at Columbia University, and he advised President Roosevelt on planning during the Great Depression.

Introduction to Thomas Adams

The developers of Letchworth also hired a young Scotsman, Thomas Adams (1871-1940), as secretary-manager of their development. Though he diligently worked to make it a success, it did not turn a profit, and he was relieved of his duties. However, by the time he left Britain for Canada in 1914, he was a widely respected expert on planning. In 1923, he moved to New York after being hired as General Director of Plans and Surveys of the Regional Plan of New York and its Environments. Over his long career, he did much to promote Garden Cityism throughout the world.

As we shall discuss below, during the 1920s, Adams, along with his American colleague, Robert Whitten (1873-1936), popularized the concept of the Floor Area Ratio as a planning tool. Those who followed them, put it into practice.

The RPAA

Howard’s ideas gave rise to two related movements—Town Planning—arranging what goes where within a city’s borders—and Regional Planning—how to organize a cluster of towns or cities best. Before long, the Garden City vision began to take root in the United States.

One pivotal figure was Charles Whitaker, the first editor-in-chief of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects, launched in Washington DC in 1913. Whitaker frequently published articles by promoters of Garden Cityism. In 1920, Whitaker moved to New York City, bringing the journal with him. While he disliked the congestion and the pollution of the Big Apple, he was able to assemble a cadre of like-minded thinkers who would come to form the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA).

While the RPAA was never a large group or had strict formalized structure, its members would go on to have an outsized influence on the debate about city planning. The original core included, among others, Whitaker, Clarence S. Stein, Robert D. Kohn, Lewis Mumford, Frederick L. Ackerman, Henry Wright, and Benton MacKaye (who would create the Appalachian Trail).

Through their writings and lectures, they popularized town and regional planning and the idea that the only way to eliminate the slums was to deconcentrate and decentralize the population. They had frequent interactions with their counterparts from the U.K. In 1925, for example, they hosted their patron saints, Ebenezer Howard and Raymond Unwin at one of their meetings.

Lewis Mumford

The leading voice of the RPAA was “its youngest and probably most brilliant member, Lewis Mumford, who became its secretary and principal wordsmith.” Mumford was born in New York City in 1895 and studied at City College and the New School for Social Research, co-founded by heterodox economist Thorsten Veblen (who will reappear in Part II.) He was heavily influenced by Scottish social theorist Sir Patrick Geddes in addition to Ebenezer Howard.

Showing his early interest in utopianism, he wrote his first book at the age of 27, entitled, The Story of Utopias, where he argued that utopian literature could provide useful ideas for the present. In 1962, his book, The City in History, won the national book award for nonfiction. For three decades, Mumford served as the architecture critic of The New Yorker. Mumford was arguably the most read and influential urbanist of the mid-20th century.[8]

Political Influence

In addition to their writings and lectures on town and regional planning, during the 1920s and 1930s, RPAA members held important positions at all levels of government. They had the ear of leaders, including that of Franklin D. Roosevelt and New York’s Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia.

During the New Deal years, RPAA member and architect Robert D. Kohn became the first head of the Housing Division of the Public Works Administration, a key post in the first New Deal Housing Program. Kohn joined the administration in 1933, having served as the American Institute of Architects’ president in the prior year. As will be discussed in the next post, Kohn was also influential in promoting the FAR concept in the 1930s.

Clarence Stein, a New York architect and partner of Kohn, would become secretary of the New York State Housing Committee in the early 1920s. This position provided considerable influence, allowing him to promote RPPA ideas. In 1923, Governor Al Smith appointed Stein as the head of the state’s Housing and Regional Planning Committee, giving him another platform.

The architect Frederick Ackerman (discussed in the next post) was a leader in the New York City Housing Authority during the Great Depression and was pivotal in promoting the floor area ratio for public housing design.

Sunnyside Gardens and Radburn

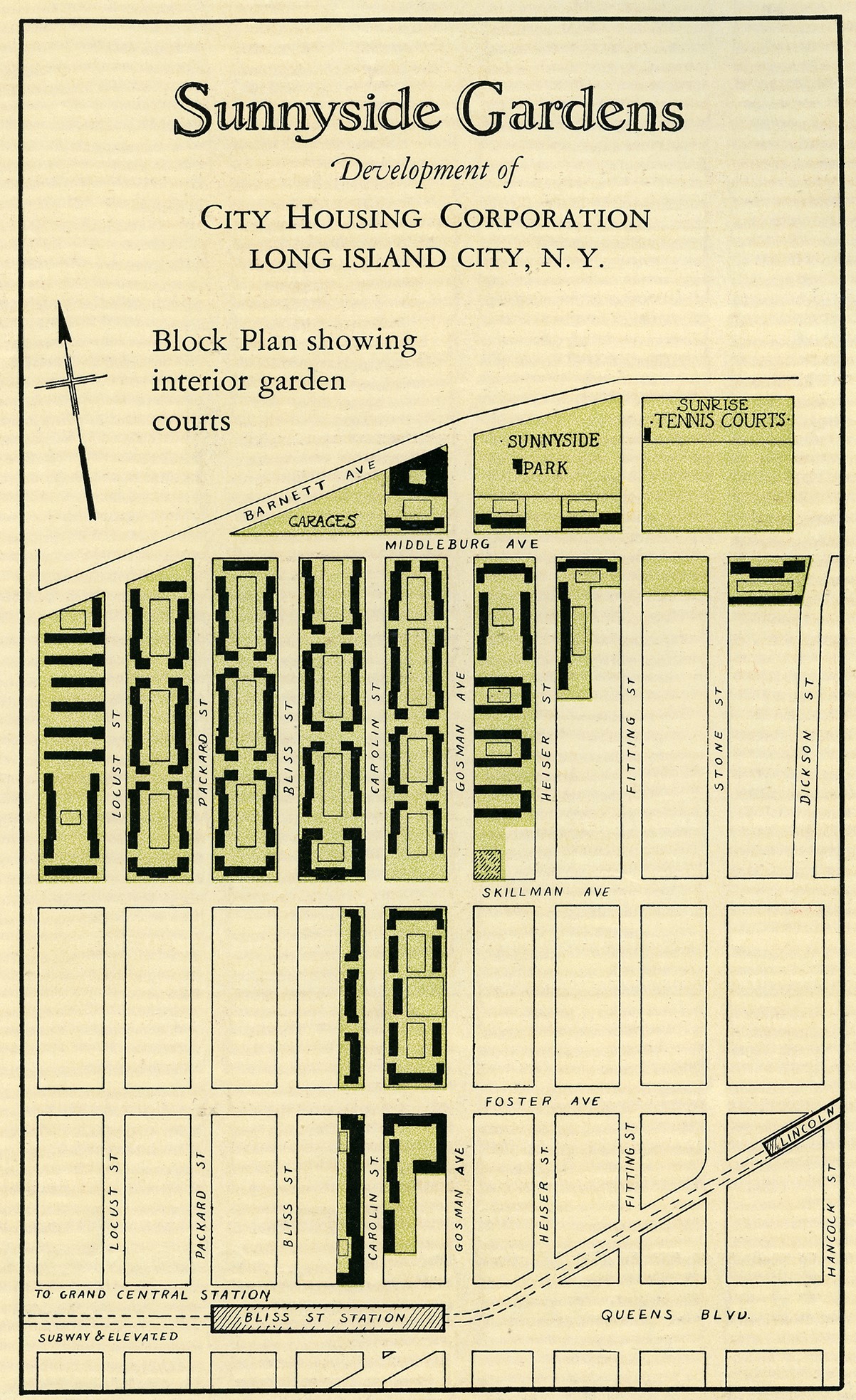

Just as importantly, RPAA members put their ideas—and money—into practice by developing some of America’s first Garden Cities. The first was Sunnyside Gardens. The project began in 1923 when Stein and Wright prompted New York real estate developer and RPAA member Alexander M. Bing to initiate it. Bing formed the City Housing Corporation, a limited-dividend company organized to raise funds and build it.

Built between 1924 and 1928, Sunnyside was located on a 70-acre tract of land in Queens. Unable to convince the Borough Engineer to modify the existing grid plan, Clarence Stein and Henry Wright—with input from Frederick Ackerman—were forced to develop Sunnyside within the traditional block system. Nonetheless, they arranged the houses in row groups along the perimeter of the block, enclosing a large central garden.

Their ideas where greatly influenced by Raymond Unwin’s designs in Britain, having visited them in 1924. While the project was one of the first attempts at from-the-ground-up Garden City planning, it could not achieve the hoped-for economies of scale nor could it offer a solution to the housing affordability problem. Residents, including Mumford himself, had to be in the middle class to afford the commodious accommodations.

Buoyed by the economic success of Sunnyside, however, the company bought 1,258 acres (5.1 km2) in Fairlawn, New Jersey, 15 miles (24 km) west of New York, which allowed for a larger, more economical town. The project, called Radburn, would take advantage of superblocks to reduce the land used for roads and infrastructure and would be designed according to the best Garden City principles. By 1931, Radburn had over 1,000 inhabitants but never came close to a true Garden City because the Great Depression drove its developers to abandon it.

The GodFARther

After several Garden City iterations, it became clear that they could not serve as a utopia for the working classes. Places like Letchworth, Sunnyside Gardens, and Radburn attracted middle-class residents interested in suburban living. Part of the problem was that Garden Cities required single-family homes with garden plots to foster healthful living. Buying or renting a house was beyond the means of most in the working classes. For that matter, the laboring classes showed little interest in leaving their dense tenement neighborhoods, where they had their social and economic ties.

If Garden Cityism were to incorporated into central cities, it would have to be constituted in a new form. The first among the Garden Cityites who understood this and was willing to adapt these principles to urban neighborhoods was the architect Andrew J. Thomas (1875–1965). He was arguably the first to apply the idea of the floor area ratio.

Thomas was born in Manhattan, where his father sold diamonds and oil paintings. He was sent to study at a military academy but was forced to abandon it after both his parents died when he was 12. He worked as an errand boy, then did a stint in California, and returned to New York to make a career in real estate. By the 1920s, he was driven to “abolish every slum in New York” if he could find financial backers.

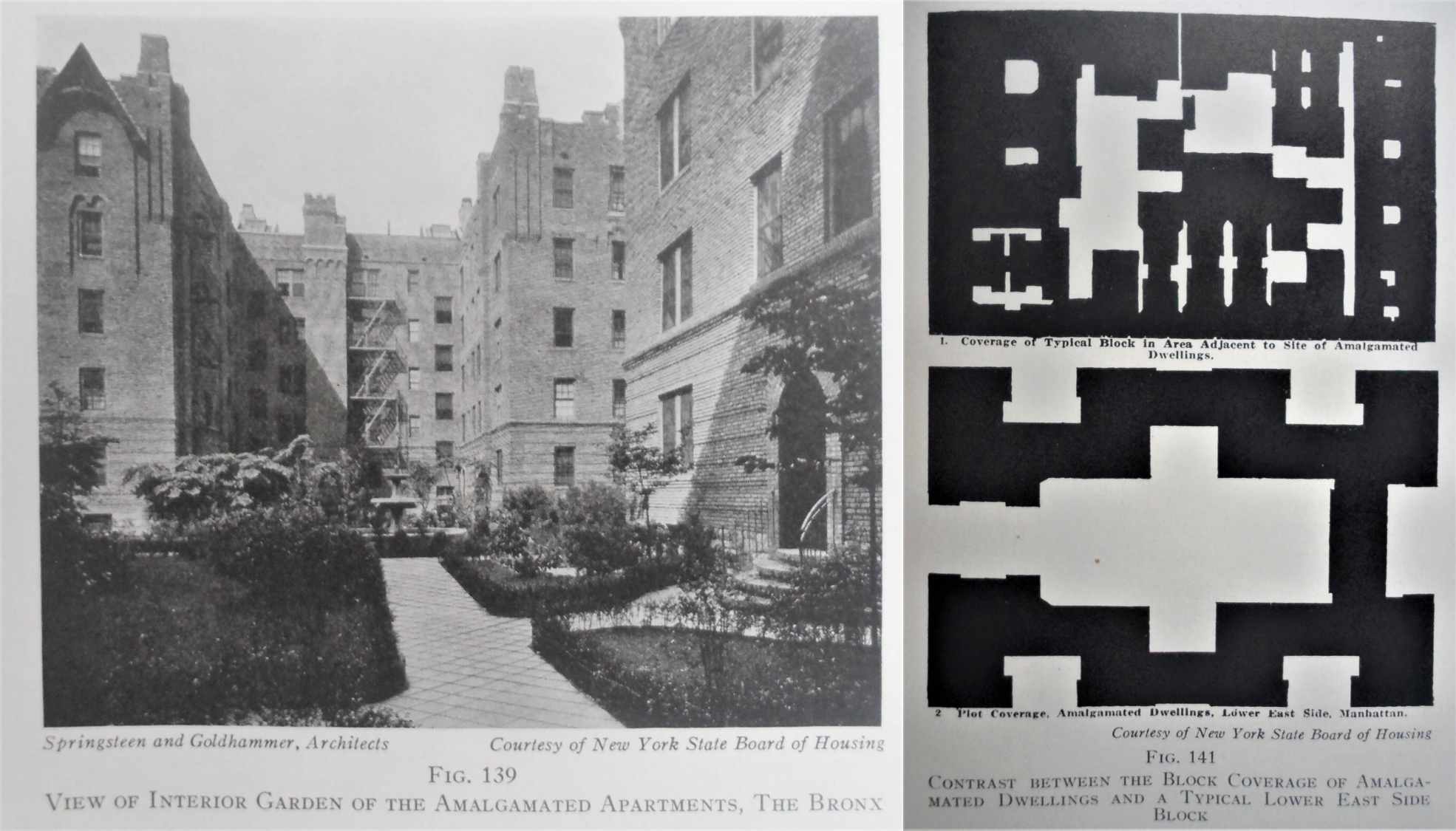

Thomas discovered that Garden Cityism for the lower classes in New York would have come through the Garden Apartment—a four- or five-story apartment building constructed amidst a sea of greenery. He argued that mass-produced apartment buildings on superblocks could be built more cheaply and arranged in a way that would provide a maximum of open space. For Thomas, it was something of an obsession to build apartment buildings on lots that had at least 50% open space, and, in his mind, the gold standard was that the building’s footprint only covered 30-35% of the lot, leaving rest for greenery.

MetLife Paves the Way

Thomas’ first chance to implement his vision came when he won a commission from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in 1922. While Thomas had prior experience designing apartments in the Garden City mold, the MetLife project in Queens was arguably the largest and most important commission that exemplified the possibility of constructing working-class, central city buildings with small footprints.

The project consisted of fifty apartment buildings for 2,000 families. The dwellings, five-story U-shaped walk-ups, covered 52% of the lot and spread out over most of the block. As historian Roy Lubove writes,

Thomas had now demonstrated the superiority of a plan which used the block rather than the narrow lot as the building unit. Eliminating scattered, wasted space, which he grouped together in courts and gardens, Thomas produced an apartment which contained an equivalent amount of space of square feet of rentable space but covered a small percentage of the land.

Following that success, Thomas received commissions from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., which aimed to spread Garden Apartments to other low-income neighborhoods. Such projects included a development in Bayonne, New Jersey. Started in 1924, its apartment buildings covered only 36% of the land. Rockefeller then commissioned Thomas to design several other projects, including one in Harlem—the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments (1928)—and another in the Bronx—the Thomas Garden Apartments (1927) on the Grand Concourse.

Thomas was the first to design the walk-up-in-the-park. Thomas’ successors would extrude their structures to create the tower-in-the-park. As we will see in the next blog post, fellow Garden Cityist, Frederick Ackerman took the baton from Thomas. He ran with it during the early construction of New York’s public housing, when he worked as an architect for the New York City Housing Authority.

The Regional Plan of New York and its Environs

During the period of Thomas’ experiments with Garden Apartments, the now world-renowned, Thomas Adams moved to New York City in 1923 to direct the Regional Plan of New York and its Environs. This project, begun in 1921 and funded by the Russell Sage Foundation, aimed to create a rational plan for the New York City metropolitan area, encompassing 5,250 square miles (13,600 km2) in three states and centered on Lower Manhattan. The goal was to rationalize the city’s transportation and land uses for a region that was projected to have some 21 million people by 1965.

Prior to Adams’ leadership, Unwin had been an unofficial advisor but was passed up for the directorship. Adams had a more practical approach to planning. When Adams took over, he worked closely with a team that included several influential leaders who created the 1916 zoning resolution, including Edward Basset, George Ford, and Robert Whitten. In this way, Adam’s leadership created a bridge between the old guard of planners who first zoned the city and the new guard of Garden Cityites, who felt that the regulations did not go far enough.

Under Adams, the Regional Plan group created two sets of volumes released between 1927 and 1931. The first was an eight-volume study, the Regional Survey, which reviewed the state of economic and real estate development in the region. The Survey was followed by a two-volume plan, which spelled out a road map for future growth. Much of the text was written or co-written by Adams.

Practicality versus Idealism: The Mumford-Adams Smackdown

Though Adams’ Garden City bona fides were secure, he was a practical man, who saw no realistic way to impose Garden Cityism on the urban colossus. As Adams’ biographer, Michael Simpson, writes,

It was clear that the Regional Plan was to be no revolutionary prescription but rather the imposition of mild public controls on a free development pattern so as to improve metropolitan efficiency and curb the market’s worst abuses while adding non-controversial public benefits like modern motor roads, parks and beaches. It represented what Adams has been saying about metropolitan regions since he had first studied London and New York a decade earlier.

Yet the Regional Plan was an anathema to the RPAA. As a united group of visionaries who saw the overcrowded, disordered city as a curse on humanity, the only solution was to create the fractal decentralized Garden Cities. The most vocal member of the RPAA was Lewis Mumford, who, in his writings, blasted Adam’s plan. As Simpson asserts,

In a root-and-branch condemnation of the Adams’s plan, Mumford criticised its “attempt to remedy a few of the intolerable effects” and its acceptance of “the fact of unregulated and unbounded growth as ‘given'”’ as fainthearted and conceptually inadequate. Regarding the whole huge effort as utterly misconceived, he believed it played into the hands of speculators for its opportunistic identification with trends would “protect and tenderly cherish the one function that all American cities have traditionally looked upon as the main end of human activity, namely, gambling in real estate“. In effect calling for the substitution of a socialist for capitalist ethic, Mumford attacked the Plan’s timidity on the role of government, which meant that “it carefully refrains from proposing measures which would lead to effective public control of land, property values, buildings and human institutions, and leaves the metropolitan district without the hope of any substantial change.”

The Birth of the FAR

From Adams’ point of view, tall buildings in New York were not going anywhere. The logical connection between Garden Cityism and reasonable implementation of it in the metropolis was to limit the bulk of structures and ensure a minimum of surrounding open space and sunlight.

These issues also preoccupied the “founding fathers” of the 1916 resolution. But amidst uncertainly about what kinds of regulations they could impose that would not be considered an illegal taking of private property, they opted for setback requirements based on the width of the street. However, by the 1920s, municipal zoning had not only been affirmed as a legitimate role of government, via the Supreme Court case Euclid v. Amber (1926) but was also revealing itself to be widely popular across America cities and towns.

By the mid-1920s, the original framers were dissatisfied with the zoning laws they shepherded into existence, as they saw supertall towers rising in places they hoped they would never go, and the problem of the “slums” did not disappear. Adams thinking about Garden Cityism combined with the analysis of men like Edward M. Basset and George B. Ford, led to the idea of regulating building bulk in proportion to the lot itself—which is what the Floor Area Ratio is all about.

The Regional Survey and Plan

The idea is featured in the 1931 Survey, Volume VI, where Adams muses about the need to control building bulk,

The importance of the principle makes us repeat it in the form frequently referred to in these pages, namely that control of bulk of buildings, including height, in relation to open spaces, is the vital question of control of buildings. It should again be noted that we use the term ‘bulk’ in relation to open area and not as merely cubic contents of building independently of open area. (Emphasis added.)

Adams takes the next logical step in the Regional Plan, Volume II, where he proposes a policy for implementation:

In residential districts the minimum open space requirement should be 50 per cent of the lot area for buildings not over eight stories in height, and not less than one square foot for each eight square feet of the gross floor area of the building. Under this scale a 12 story building would have 60 per cent open space. While the above should be a minimum standard for intermediate residential areas, there are large portions of such areas where the open space requirement should be one square foot for each four square feet of gross floor area. This will mean 50 per cent open space for a four story building, 60 per cent for six stories, and 75 per cent for 12 stories. This will insure provision for open space on the lot roughly proportionate to the population density. (Emphasis added.)

In short, Adams argues that the best way to regulate building density was to require so many feet or meters of open space per so many floors of building height–this is the FAR in its essence.[9]

That Adams was influenced by Andrew Thomas is clear. Volume II of the Regional Plan contains numerous photographs and renderings. The apartment buildings are only those designed by Andrew J. Thomas. Below the image of the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments is a laudatory caption.

Robert Whitten

But Adams’ thinking did not emerge in a vacuum. An important influence and colleague was Robert H. Whitten (1873-1936). Whitten was born in South Bend, Indiana, and received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan in 1896. Only two years later, he received a Ph.D. from Columbia University. For nine years, he was a librarian for the New York State Library, and then was the library’s statistician.

In 1913, his career trajectory changed when he was hired as the secretary of New York’s City Planning and Zoning Commission, which was responsible for creating the comprehensive zoning resolution of 1916. This made him one of the “founding fathers” of New York zoning.

Following his work in Gotham, he became a planning advisor to the City of Cleveland, where he wrote, in 1921, a plan for zoning Cleveland. He would also write zoning plans for Boston and Atlanta. Whitten returned to New York to become a member of the Regional Plan team; he co-wrote, along with Adams and Basset, a chapter on planning in unbuilt areas in Volume VII of the Regional Survey.

Throughout his career, Whitten wrote widely about the need for, and benefits of, zoning. And he, like Adams, also concluded that the best way to limit urban building density was through some method of limiting floor area based on lot size. At this point, we cannot say whether Adams influenced Whitten, Whitten influenced Adams, or the idea was pulled from others. But we can say that at the same time, both were arguing the same thing: That good planning required taller buildings to be surrounded by proportionately more open space.

Whitten’s goes FAR

In his 1931 article, “Open Spaces for Residential Buildings,” Whitten clearly echoes this when he writes,

Probably the most efficient form of open space requirement in connection with apartment houses is one that relates the required open space to the gross floor area of the building. A requirement deemed appropriate for small apartment houses in certain sub-urban areas provides that there shall be one square foot of open space for each two square feet of the gross floor area of the building. This means that a three-story apartment building must leave sixty per cent of its lot area uncovered, a six-story building seventy-five per cent uncovered, and so on. (Emphasis added.)

The Next Chapter

Through the words of the Regional Plan and the community of Garden Cityities, on the eve of the Great Depression, a FAR was born and launched into the public sphere. The idea that as buildings got taller they must get thinner was now in the air in planning circles.

Over the 1930s, this concept would be formalized by RPAA members and obtain its first manifestations in written urban policies. In the next post, we turn to growth and development of FARtopia.

Continue reading my three-part series on the 1916 New York Zoning resolutions here.

Thanks to Maria Thompson for editorial assistance.

—

[1] The FAR is typically measured by taking the usable building area and dividing it by the area. An old style tenement walk-up with five stores might have an FAR of about 4, for example. The FAR is called different things around the world, such as the floor space ratio, the floor space index, and the plot or site ratio.

[2] FARs are calculated from the NYC PLUTO file.

[3] From 1942 to 1957, Chicago limited skyscrapers to be 144 times the lot area, which, assuming a 12-foot floor height, is about an FAR of about 12. Chicago was the first big city to limit skyscrapers in this way. New York added FAR restrictions to its suburban districts in 1940.

[4] The idea of the floor area ratio was clearly in the air as early as the 1910s, if not earlier. An engineer, Reginald P. Bolton, interviewed for the 1913 Heights of Buildings Commission report recommended to cap buildings at “nine times the gross plot area in gross interior floor areas” (page 183). And, in fact, as discussed in Fischler (2017, Plan Canada, Summer, 36-41 ), the wealthy suburban community of Westmount in Montreal capped their houses to have a maximum floor area equal to the lot size (and FAR of about 1).

[5] Ironically, for the fans of Jane Jacobs, the FAR restrictions have been a way to impose their version of low-rise Greenwich village utopia in the 21st century.

[6] I want to be clear that just because the FAR caps in New York and other cities are overly restrictive does not mean I advocate for abolishing land-use regulations. The point is to find the right balance between promoting the benefits of density while reducing their negative impacts, like congestion, noise pollution, and shadows. Overly restrictive regulations raise housing prices, reduce urban growth and employment, and generate a feeling of resentment that the city is a fixed pie pitting winner against losers. Rewriting regulations and “upzoning” the city based on the knowledge we have in the 21st century is the way to go. The 1961 zoning codes were implemented 80 years ago when both the urban conditions and the thinking were much different.

[7] Howard’s first edition was called, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform but was reprinted under the title, Garden Cities of To-morrow.

[8] As the height of his career, Jane Jacobs published her now-classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, where she called out Garden Cityism as wrong headed and harmful for urban life. Her version of utopia was to embrace the tenement districts. To these followers of Howard, tenements were a blight on humanity. See Mellon (2009) for the debate between Mumford and Jacobs.

[9] As mentioned in note 4, in a technical sense Adams was not the first to propose an FAR-like idea. Other places had experimented with FAR-like concepts before the Regional Plan, but given the importance of New York, and the fame of Adams, his words would likely have been the “FAR shot” heard around the world.