Jason M. Barr July 10, 2018

Author’s note: The paperback of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers was recently released. This blog post has been adapted from Chapter 9 of the book.

The Roaring Twenties remains a mythical time in American culture—an age of danger, of heroes, of unrestraint. Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Clandestine speakeasies served bathtub gin to flappers, swinging to the new jazz music. Babe Ruth became the Sultan of Swat. And supertall skyscrapers sprouted upwards like Jack’s beanstalk.

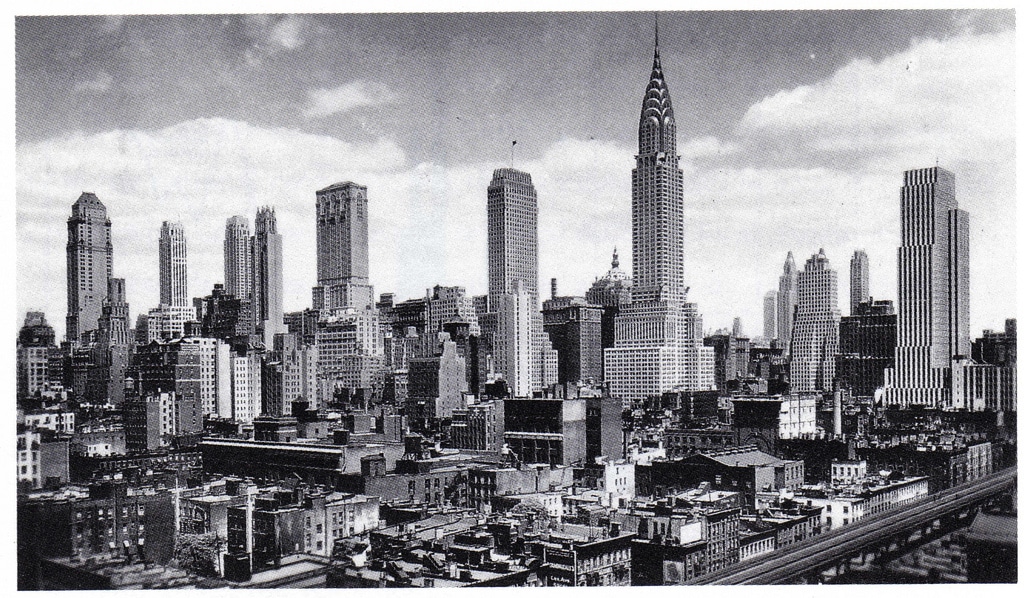

Though the skyscraper was born in the last two decades of the 19th century, it was a generation later when it reached its true potential. From May 1930 to May 1931, three super-giants—each the world’s tallest for a spell—lorded over New York. First was the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building (71 floors). Next came the Chrysler Building (77 floors). Finally, was the granddaddy of them all, the Empire State Building (102 floors).

They were completed at the peak of a skyscraper construction spree that ran from 1925 to 1931. From these three giants, the natural conclusion is that the boom of the Roaring Twenties emerged from the irrational euphoria of the time. With financing flowing like wine, the newly-rich business tycoons got caught up in the craziness and felt compelled to memorialize their egos in steel and stone.

The “Office-ification” of America

The rise of the Manhattan skyline in the Roaring Twenties—a bit heady to be sure—was due, however, to more mundane reasons. The post-World War I era was the culmination of the Industrial Revolution. It was the “office-ification” of the American economy. Between 1870 and 1920, the population of the United States had doubled; during the same period, office space requirements had risen from about one square foot per capita to five square feet. The combined forces of increased population and office space needs meant that by 1920 the country needed ten times as much office space as in 1870.

In the early years of the twentieth century, corporate America began introducing a series of goods and services that radically transformed the nature of household life. The 1920s was the decade when America began to embrace consumer-oriented culture, which was made possible by the dramatic improvements in industrial productivity. New York City, the center of finance, transportation, communication, marketing, and legal services, was the metropolis—the mother city—that helped enable it.

Manhattan and the Automobile

A good example of this is the automobile. The “horseless carriage” was invented as early as 1769. Over the 19th century, tinkerers, “steamhackers,” and small-time entrepreneurs built hand-crafted models for their rich clientele. But it was, of course, Henry Ford’s idea to mass produce cars and trucks that changed everything. By taking advantage of interchangeable parts and the assembly line, Ford was able to exploit economies of scale—go big to go cheap.[1] For the first time in World History, the common folk had access to their very own personal rapid-mobility units.

The growth of the automobile was tied up with the growth of the Manhattan skyline—each feeding the other. Out of Manhattan office buildings, firms were selling financial, marketing, technical, and legal services to the car industry. This, in turn, increased car sales, which increased the demand for New York services, and so on. Many a Detroit company set up offices in Manhattan’s Automobile Row to be close to the action. To be clear, I don’t want to overstate the case that it was the automobile, per se, that lead to the Manhattan skyline. It did not, but rather the auto industry’s growth was exemplary of the type of relationships between New York City and the American economy more broadly.

Walter Chrysler

When we look at the Chrysler Building, we see its chrome spire ascending upwards, as if to announce the power of capitalism and greed to reach the heavens. This view is given currency by focusing on Walter Chrysler’s desire to erect the world’s tallest building, and which simultaneously required head-to-head “combat” against the Bank of Manhattan Trust for that right. We are fed the legend that William Van Alen, Chrysler’s architect, patiently waited until the Bank of Manhattan Building was topped out, and then gloriously lifted the—craftily hidden—steel spire up over the top floor to claim the prize of “World’s Tallest.”

Burying the Lead

The buried part of story about the Chrysler Building is not about this dramatic height competition, but rather about Walter Chrysler himself. What was an automobile magnate doing in New York City?[2] Chrysler began his ascent in Flint, Michigan, were he successfully copied Ford’s production line innovations for General Motors in 1911. After disagreements with his boss, William Durant, Chrysler moved to New York to take control of the Willys-Overland Company, which had its facilities in Elizabeth, New Jersey. After that he took the helm of Maxwell Motor Company, which he then turned into Chrysler Corporation.

He found that to grow his business, he needed to be in New York, close to the financing, expertise, and marketing. In 1935, Fortune Magazine recalled a story about Chrysler’s start as a budding mogul. In 1924, rejected by both New York bankers, who refused to finance him, and the New York City Automobile Show, which refused to display his car,

It was at this juncture that Walter Chrysler showed his courage-or more precisely, perhaps, his nerve. He hired the lobby of the Commodore Hotel [next to Grand Central Station] a few blocks from the show and wheeled his cars in. And he then took personal charge of the situation, standing guard to see that no one guessed out loud at the new car’s wheel base and refusing for a week to name his price. When he did name it-when it had become evident that the miniature dreadnought had stolen the show and the time had come for orders-he wrote his figures on a card, handed them to Joe Fields, his sales manager, and walked away.

The Developers

Though Chrysler felt the need to be in New York, and this eventually lead him to build the Chrysler Building (which was his own building, and not that of the car company), he was not the typical developer who built the skyline.

The vast majority of builders were either born in New York City or emigrated as small children with their families from Eastern Europe. Many of them had begun their early careers in the Garment District as tailors or small-time clothing manufacturers. The experience they earned was then used in real estate—building lofts and showrooms, and eventually office towers.

A typical example is that Abraham E. Lefcourt, who was born in 1877 and came to America in 1882. He started out hawking newspapers on the streets of the Lower East Side, and later worked in the garment industry. In 1910, he built his first structure, a 12-story loft building for garment businesses on West 25th Street. The first two floors housed Lefcourt’s own women’s apparel manufacturing company. The success of the endeavor prompted him to move into the real estate business full time. Between 1910 and 1930, Lefcourt constructed 31 commercial buildings in the city.

The Railroad Stations

The reason that men like Lefcourt built was that during the second half of 1920s, office rents (adjusted for inflation) were at an all-time high. Businesses were willing to pay the cost because being in New York increased their profits. The high rents motivated developers to provide more offices in the sky. This is the real reason for building boom of the Roaring Twenties.

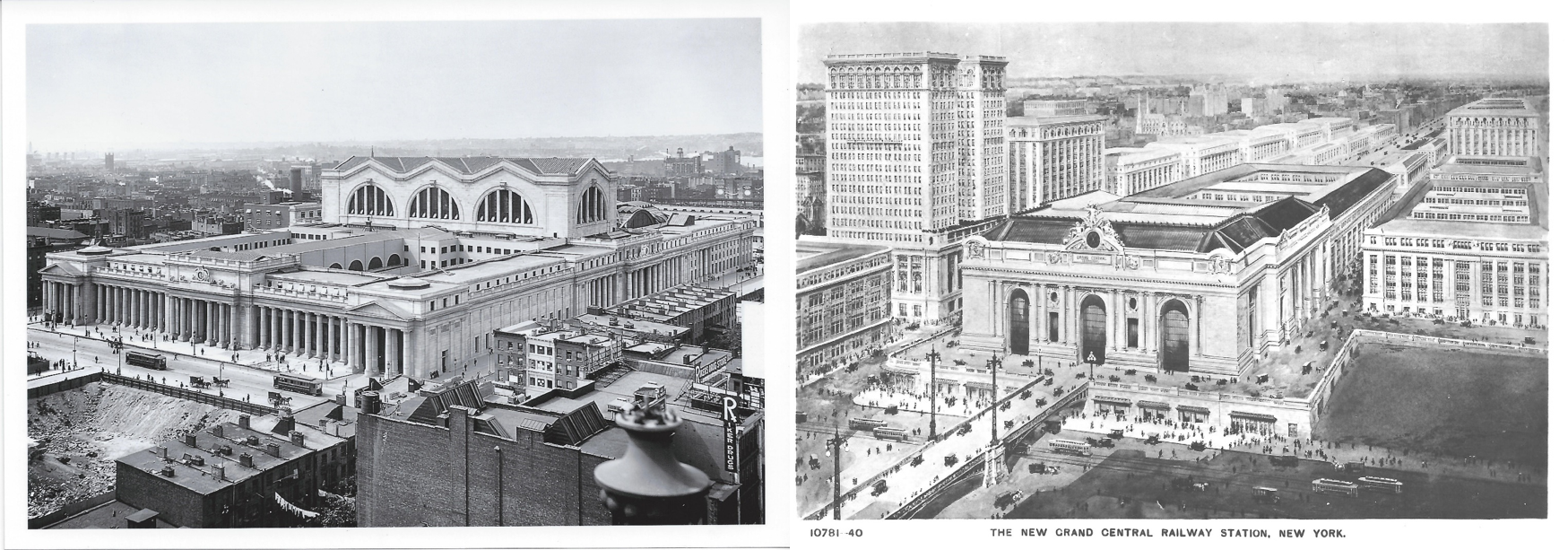

Before World War I, two magnificent railroad depots were completed in the city—Penn Station (1910) on the west side at 33rd Street and Grand Central Station (1913) on the east side at 42nd Street. Together they created a kind of flower pot for modern midtown Manhattan to grow. These two transportation hubs, combined with the expansion of the subway system, drew millions of people to midtown each week to work, play, and shop.

Around Penn Station were the Garment District offices and factories. Moving east, near Herald Square, was the retail zone, including the giant Macy’s Department Story, which sold the wares made just a few blocks away. Going north was Times Square, the city’s entertainment center. Then going east were the gleaming new office towers that housed the corporations that produced America’s goods and services.

Who Built the Skyline?

So, when you look at the Deco Giants remember this: they were not built by the raging egos of self-absorbed tycoons. Rather they were built mostly by local real estate men, supplying the demand for office space in America’s largest and most important metropolis. The skyline was created because your grandparents and great grandparents wanted to buy fashionable clothes and modern conveniences. New York was the headquarters headquarters that made this possible.

—

[1] As an important side note, his plant was made possible by the mass production of electricity, the success of which was first demonstrated in New York City by Thomas Edison in 1882. The cost of electricity steadily plummeted in the early 1900s allowing for large-scale manufacturing. Also, Henry Ford knew a thing or two about electricity. In 1890, Ford was hired as an engineer for the Detroit Edison Company. In 1893, his abilities earned him a promotion to chief engineer.

[2] For those interested in the internment locations of America’s social, economic, political, and artistic elite, Walter Chrysler, along with Washington Irving and Andrew Carnegie, is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Westchester County, near the Hudson River, 30 miles north of the Chrysler Building.