Jason M. Barr (@JasonBarrRU) March 23, 2021

Erin go Tweet

On March 9, 2021, Professor Ronan Lyons, an economist at Trinity College Dublin, tweeted about one of my research papers on global tall building construction.[1] Dr. Lyons has 24,000 followers (two orders of magnitude more than me, but you can follow me on Twitter here). His tweet mentioned the paper’s findings for Ireland. This set off a tweetstorm, with no shortage of opinions—mostly against—about skyscrapers in ancient Dublin town. This post is my response to that tweetstorm.

The Paper

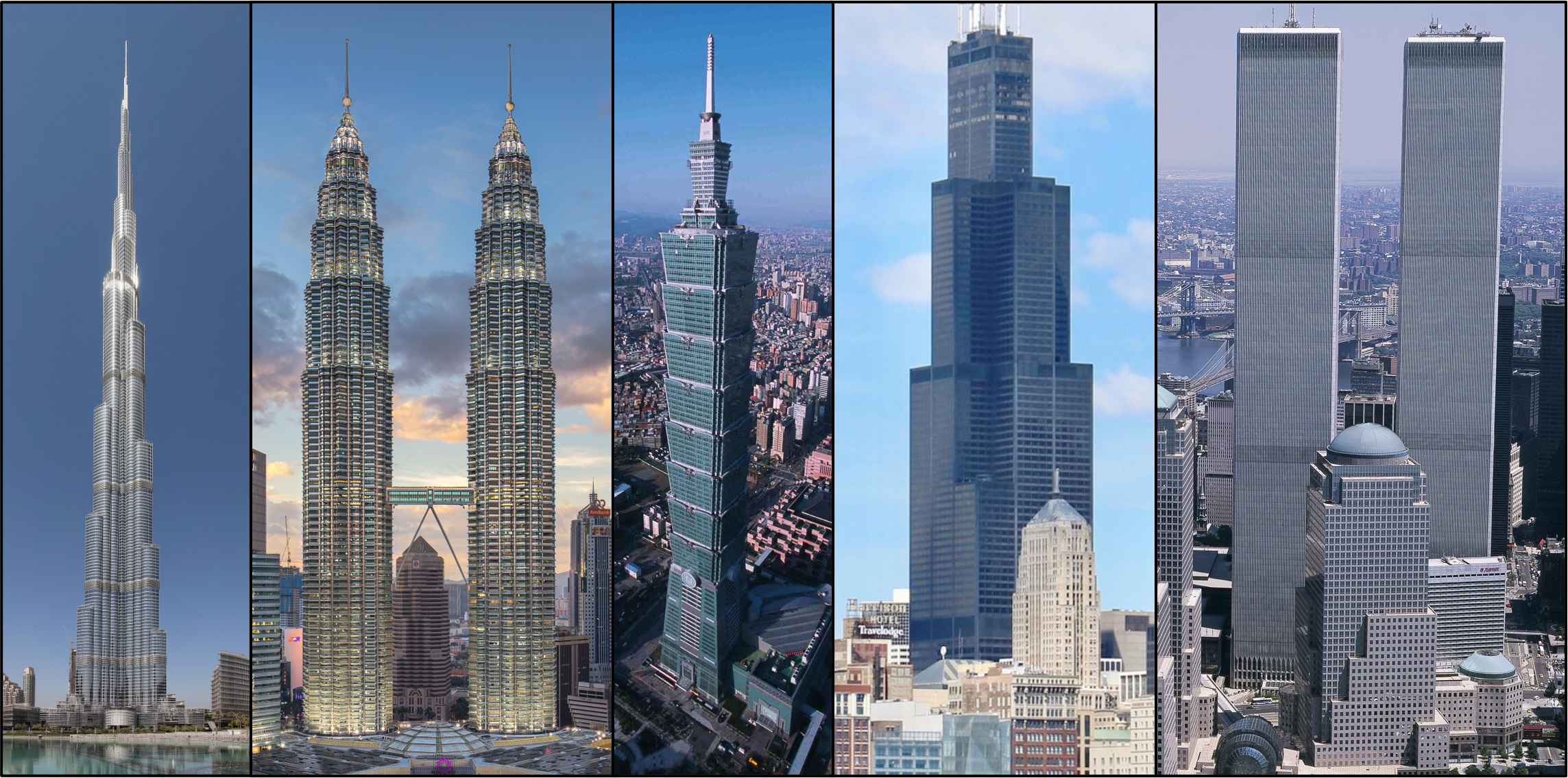

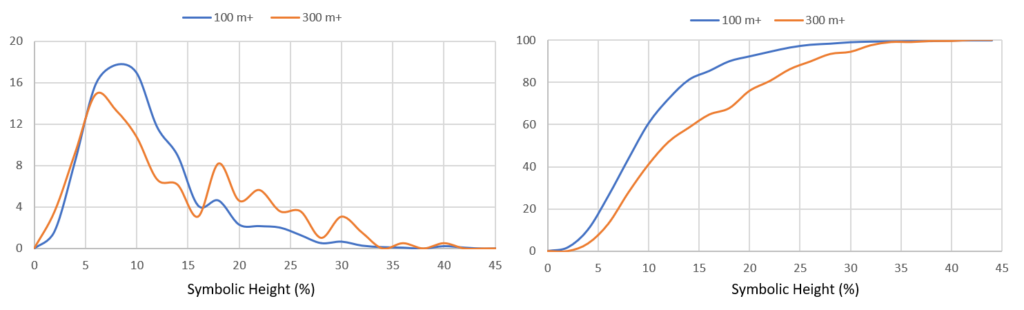

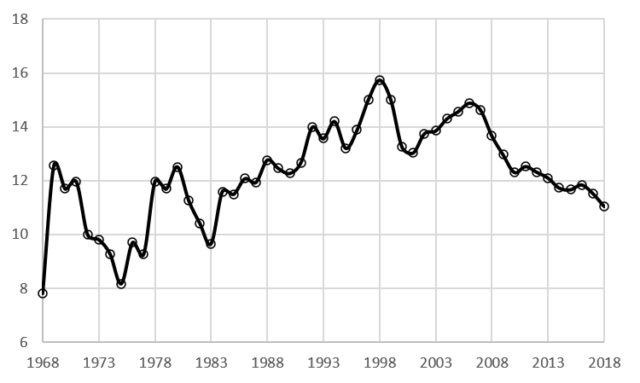

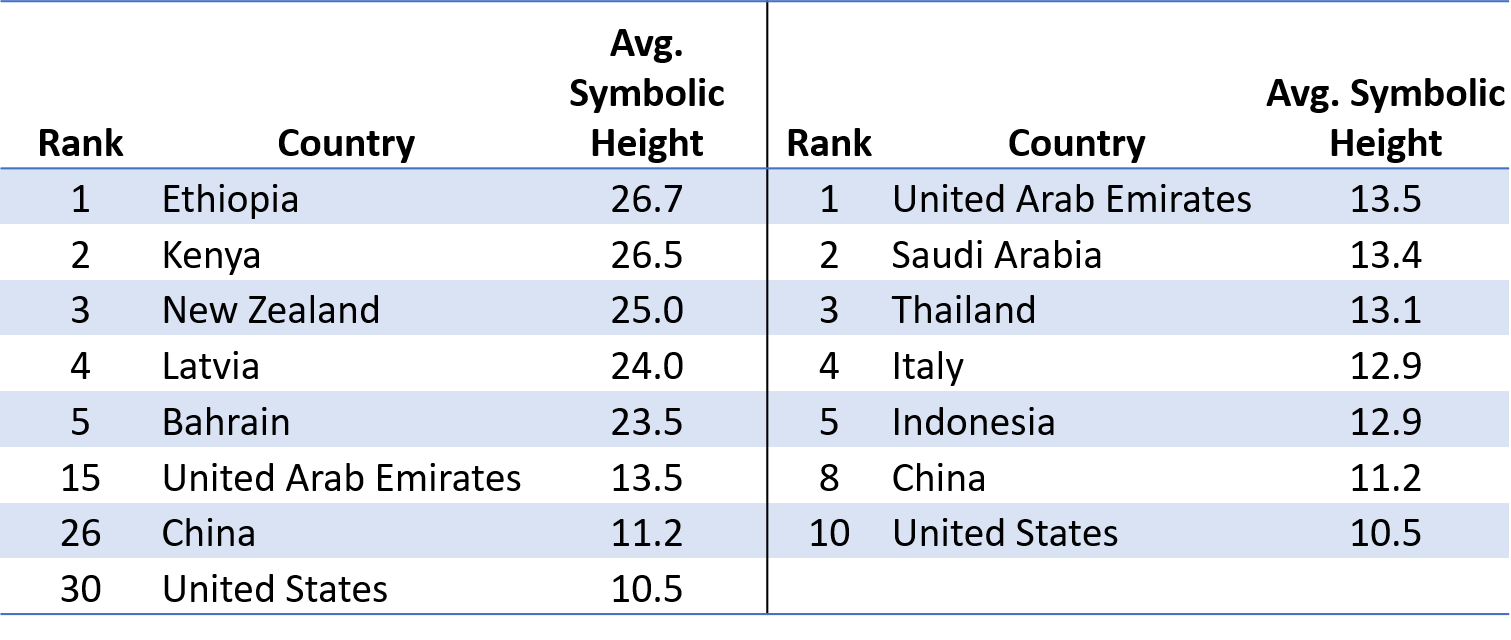

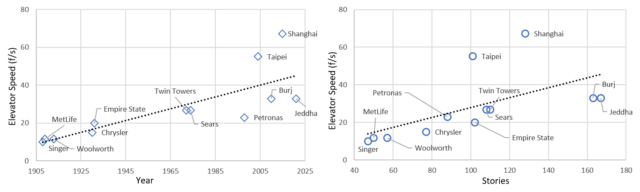

Before I get to Ireland, let us turn to the research that started the whole kerfuffle. The paper is “Cities without Skylines: Worldwide Building-height Gaps, their Determinants, and their Implications” (by Remi Jedwab, Jan Brueckner, and me). The study attempts to understand the causes and consequences of building height restrictions around the world. It is the first to measure global differences and attitudes towards tall buildings.

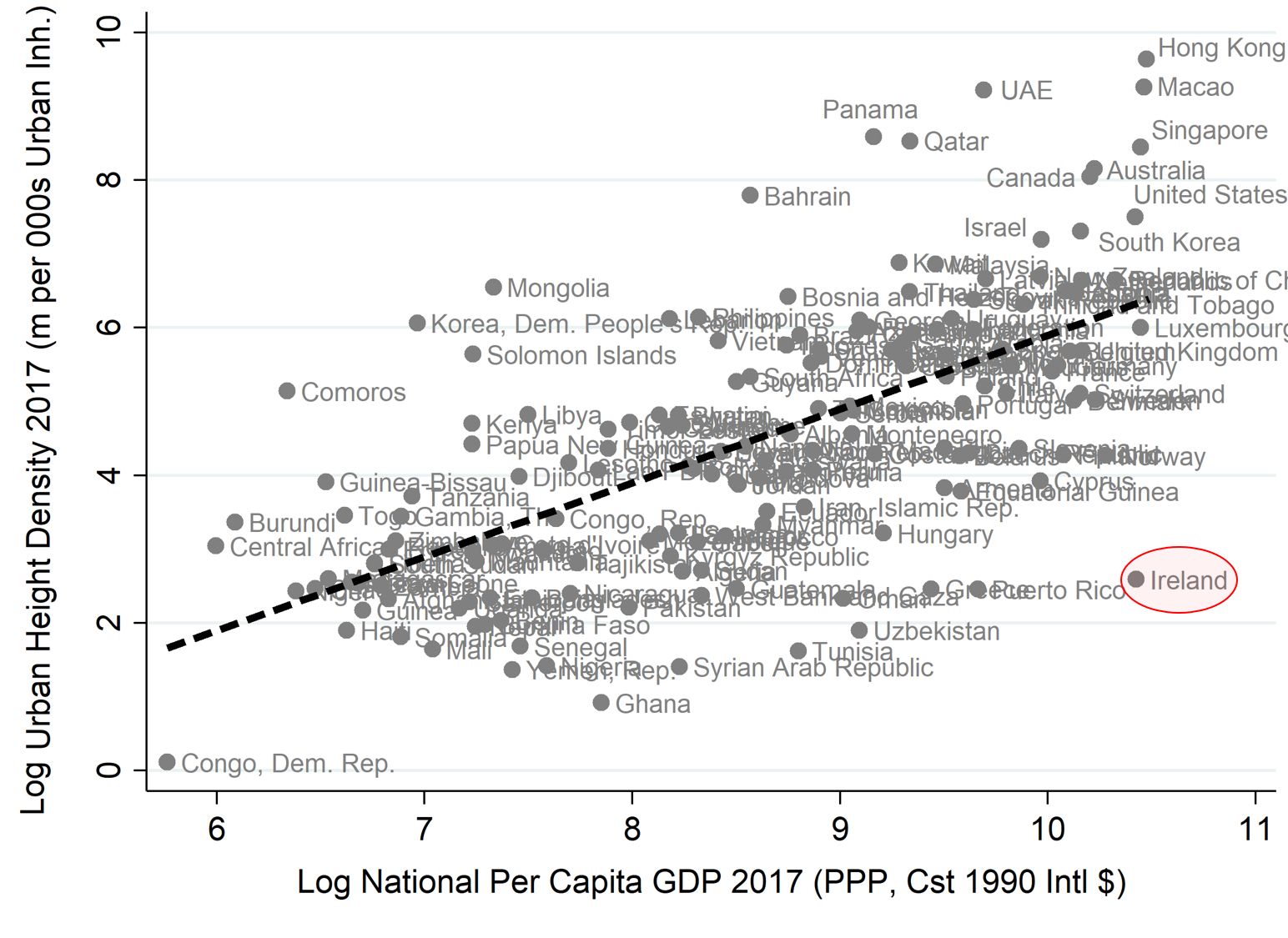

We estimate the degree to which skyscrapers are “missing” from every country due to stringent building height regulations. To do this, we come up with a prediction of how much building height a nation “should have” if its real estate market was relatively open, and then compare this to the actual total building height. We call the difference the “building-height gap.” Higher gaps mean more “missing” buildings, given the income levels.

No Free Lunch from the Fear of Heights

The paper shows that the building-height gap is highest for richer countries and is driven mainly by stringency in the housing sector. The evidence also suggests that wealthier countries with higher gaps have older cities and are more interested in preserving their national heritage. Just as importantly, we also find that the gaps are positively related to sprawl, air pollution, and higher housing prices. In short, we see that countries with more restrictive building height regulations are imposing a degree of economic harm on their residents. One might say that there is no free lunch from the fear of heights.

The Tweebate

When we crunched the numbers and came up with the country that had the largest height gap per million urban residents, it turned out to be Ireland, which has no skyscrapers (100 meters or taller), though one is seemingly in the works. Across the world, there is a strong correlation between national income and building heights. Richer countries build taller, on average, because they are more urbanized. However, Ireland—and Dublin, in particular—is both relatively wealthy and has robust business services and financial sectors, which tend to promote tall building construction for both office and residential purposes.[2]

Professor Ronan argued that Dublin should not be so afraid of heights if it is genuinely concerned with housing affordability. Building upper-class high-rises can help, albeit in a small way, to reduce housing prices more broadly. This comment set off a flurry of responses about tall buildings’ impacts on affordability and urban form. Common among them were the typical tropes about skyscrapers and cities. I want to take this chance to rebut some common misconceptions. It is better to do it in long-form than on Twitter with endless 280-character back-and-forth jabs—peppered with personal attacks—which I find emotionally stressful and ultimately a poor vehicle for fruitful discussion.

Revisiting the Myths

Myth #1: “Building up is pricing up”

Because skyscrapers are expensive to build and operate, people believe that, by their very nature, they increase the price of housing, or as one Tweeter put it, “building up is pricing up.” But the opposite is true. The idea that building up is pricing up confuses correlation with causation.

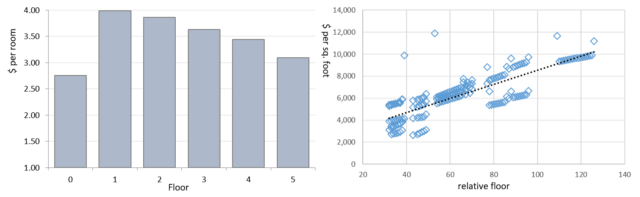

Skyscrapers are a response to high land values. When land is expensive, it signals that the demand for that location is high and that people are willing to pay more to be there. As a result, developers respond to the demand by building tall. A high-rise building in a low-density suburb makes no economic sense. The prices of land do not justify the expense of going tall. This is why the vast majority of tall buildings around the world are in central metropolitan areas.

Anytime a building comes online, it slightly increases the supply, which reduces prices. This impact is often hidden in large cities with relatively little new construction because the demand side–which pumps prices up–swamps the supply side. However, if you dumped many high-price units on the market at the same time, it would push prices downward. Would it reduce prices all around the city? No, but it would certainly help in, say, a one-kilometer radius around the new construction.

Myth #2: “Skyscrapers cause gentrification”

Gentrification is caused by high demand relative to low supply. When a new high-rise goes up, it has two effects. First is the supply-side effect, which reduces neighborhood prices, ever so slightly. However, because the tall building now allows for a denser neighborhood, it increases the demand for neighborhood services, such as coffee shops and pubs, which can draw more people in, further raising real estate prices.

But in a smooth-functioning market, rising prices due to increased amenities will be met with more housing, which would reduce the number of people who feel pushed out by the neighborhood’s increased attractiveness. Gentrification is caused by frictions or barriers to new construction, including tight building regulations and high construction costs. These barriers generate “fixed-pie” neighborhoods: those who can afford it can get a slice of the pie. The rest need to go elsewhere. More housing increases the size of the pie.

Myth #3: “Hong Kong has lots of skyscrapers. Hong Kong is expensive. Therefore, skyscrapers must make Hong Kong expensive.”

While I will have more to say about Hong Kong in a future post, the opposite of this idea is true. Hong Kong is expensive not because of its skyscrapers, but despite them. Hong Kong’s problem is due to its unique land and housing markets.

The first is land scarcity. A large swath of the city has mountainous, steep terrain and is unsuitable for building. More importantly, the government owns all the land and doles it out in varying amounts. While the precise nexus between land supply and housing supply remains debatable, developers’ ability to quickly adjust the housing stock based on demand is highly constrained.

Additionally, Hong Kong has a dual housing market, which tends to lower affordability. 45% of housing units are owned by the government. The rest is free market. This two-tiered system encourages high-prices in the free one because no one leaves the cheap public housing (once you apply, the average waiting time is 5.7 years to get a public housing apartment), forcing the rest to seek out scarce market-rate shelter.

When big cities have two-tiered systems, the lower and middle-class residents who cannot get into the subsidized units are the ones who invariably suffer. Because new construction in the unregulated sector is limited, it will mostly be dedicated to high-priced housing accessible to the upper classes, leaving the rest to bear the brunt of the shortages.

Myth # 4: “Developers want to build skyscrapers everywhere.”

Skyscraper construction is only profitable in locations where land values and real estate prices are high enough to incentivize construction. Because of their size and their occupants—upper-income folks—they tend to be viewed as agents of income inequality and gentrification.

But in any city with many building restrictions, developers find a way to provide new housing where there are the greatest profits—in the city center. There are many low-rise, middle-income neighborhoods throughout a city where new construction at slightly higher densities—for example, replacing one-family homes with four-story apartment buildings—could be profitable. But residents do not want new construction in their neighborhoods.

They shout, “Not in my backyard!” and then complain when skyscraper developers build high-rises in other people’s backyards. If you limit construction throughout the city, skyscrapers appear in the central pockets where developers can “squeeze” them in and make money satisfying the demand. They cannot satisfy the demand elsewhere because restrictive zoning or building regulations prohibit them from doing so.

Myth #5: “Goldilocks density should be imposed throughout the city”

Jane Jacob’s 1961 classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, sparked a debate about the ideal urban neighborhood. Jacobs wrote about her Greenwich Village street in virtually utopian terms. Recent research has confirmed that dense, low-rise mixed-use neighborhoods have all sorts of desirable characteristics: They have a diversity of people and amenities, their carbon footprints are lower, and they “feel” warm and cozy. These historic, pre-automobile neighborhoods represent in the minds of many a Goldilocks neighborhood—not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

The Goldilocks supporters rail against the “plutocrat” developers destroying neighborhoods with their elitist skyscrapers. The policy implication of this view boils down to “Not in my backyard!”—preserve the historical communities in amber to keep them precisely as Jane Jacobs described them six decades ago and ban tall buildings in urban centers. In essence, take the Paris route to urban land use policy: Forbid anything that does not conform to their notion of the perfect city.

In the Balance

Do not get me wrong: I love Greenwich Village and old New York, and historical preservation is vital! But we must also recognize the costs of these positions—historic preservation limits new construction, which raises prices. Additionally, the notion that there is one ideal density that should be mandated by law is absurd.

Skyscrapers in the center represent the demand to live in dense central areas, and if people demand more density, then tall buildings fulfill a need.[3] Areas farther out from the center should be leafier and less dense—that is the benefit of living farther away. True Goldilocks density is a moving target, and land-use policies should reflect this by being flexible.

Having said this, if New Yorkers, like Parisians, want to “vote” to preserve their city as it existed a century ago, they should be clear that they prioritize aesthetics and historic preservation over affordability and that the closed city is to be only for the rich who can buy million-dollar studio apartments in low-rise Greenwich Village and let everyone else fend for themselves.

Myth #6: “Skyscrapers destroy the ‘human scale‘”

The perception is that tall buildings next to low-rise buildings or tall tower-in-the-park style high-rises destroy the “feel” of the city. This is an issue, aside from the economics of housing supply, that merits serious discussion. The fundamental question we face in the 21st century is how to create cities that are both affordable and enhance life satisfaction.

Detractors of tall buildings say that towers make the city “feel cold” and dampen the vitality of the streets. True, not all tall buildings fit within the urban fabric, and glass boxes can be alienating to passersby, but two important points need to be made.

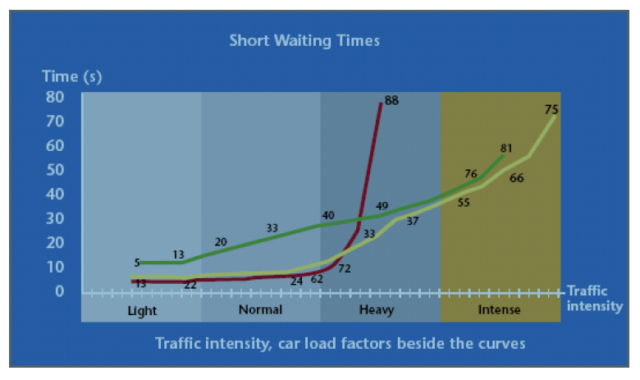

First is that human scale and quality of life are more directly harmed by dependency on automobiles. Dense urban neighborhoods are inherently more vibrant than those with, say, sprawling suburban tracts and strip malls, or big cities that build six-lane highways directly through the center. If the aim is to create more livable cities, we should focus on creating critical densities that promote diverse populations, various uses, and more mobility.

Automobiles are a bad way to move people. They take up a lot of urban land for roads, parking and storage, and they are too easily subject to congestion. Four automobiles will, optimistically, carry eight commuters during rush hour. For the same length, a bus or streetcar can carry perhaps 50 or more people. Cars also promote sprawled-out, low-rise living.

If cities are really concerned about the quality of life, the focus should be on improving non-car-based mobility among urban residents first and then allowing neighborhoods to densify up based on where people want to be. Increasing density along subway lines and commuter rails is a great way to start.

Urban Umami

Secondly, as I have argued elsewhere, if we want to improve the feel of cities, we have at our disposal new methods and technologies that allow us to better understand human preferences and the psychology of streetscapes. Once we know this, municipal regulations can incentivize good urban design—to make new construction feel less oppressive in people’s minds, and blend better with the historical urban fabric.

Imposing low-rise density in the city center is inherently exclusionary since it generates housing shortages in the name of “human scale.” We all want to live in a city that feels nice, but only the rich can build cities that uphold their notions of ideal beauty but ignore economic realities.

Guiding Principles

While I will have more to say in future posts about urban policies that get us to cities that are both affordable and high-quality, we need to begin by clearing away the misconceptions about tall buildings. So, at the risk of repeating myself, let me summarize.

Supply and Demand

First, real estate markets operate like all markets—according to the laws of supply and demand. The more these laws are subverted, the more they wind up harming residents, usually in the form of unaffordable housing due to excessive building regulations and other frictions. All cities need to find the right balance between regulation and growth, and the current global affordability problem is driven, in large part, by the desire to guard and preserve the present and past city against fears of the future city.

Tall Buildings are Efficient

Second, skyscrapers are built in central areas where demand for housing is high. As such, they represent an efficient use of land. The fact that skyscrapers are more visible and tend to be for upper-income residents should not distract us from the fact that more housing is needed at all income brackets and at locations where cities experience an extreme “shortage” of housing.

A look at New York, for example, shows that about 50% of the entire residential land area is currently used for one- and two-family homes. This is inefficient. We should spend less time worrying about Manhattan skyscrapers and more time getting neighborhoods with four houses per acre (10 houses per hectare) to add more units.

Skyscrapers do not Belong Everywhere

Third, skyscrapers do not belong everywhere. They are not economically rational or practical outside central areas. In suburban districts, densification should entail converting smaller buildings to those that are a bit denser. People should have the right to convert one-family housing to two- or three-family housing or convert garages to rentable apartments, for example.[4]

More housing, regardless of the occupants’ income, can help reduce the price of housing. The key is that for a city to remain affordable, it must increase its supply faster than prices rise. When this happens, housing prices moderate. Tall buildings can help, though by themselves, they are not sufficient.

Missing the Forest for the Trees

Fourth, getting angry about one high-profile project each time it crops up is missing the forest for the trees. Focusing on one building or neighborhood at a time is not only inefficient but harmful for residents more broadly. Policies need to be citywide, and they must ensure that every neighborhood gets its fair share of housing based on the demand for those neighborhoods.

Livable Cities

Fifth, livable cities must begin with sound economics. If we want livable cities, we should abide by three principles.

- Let density naturally arise where people want to be and let mixed-uses and diversity emerge along with it. High-rises should go where high-rises should go, and low-rises should go where low-rises should go.

- Excessive automobile dependency subverts quality of life more than tall buildings. Simply creating central-city congestion pricing is not the answer. Any transportation system needs to maximize mobility and access, including pedestrian routes and bicycle usage.

- Modern social science methods can now be used to better understand what kinds of building and street designs make people feel more at ease and encourage people to come out onto the streets. But implementing good design practices while ignoring the economic and transportation issues is insufficient to produce better cities. If we limit new construction, we wind up getting better-designed cities for rich people.

The Future City

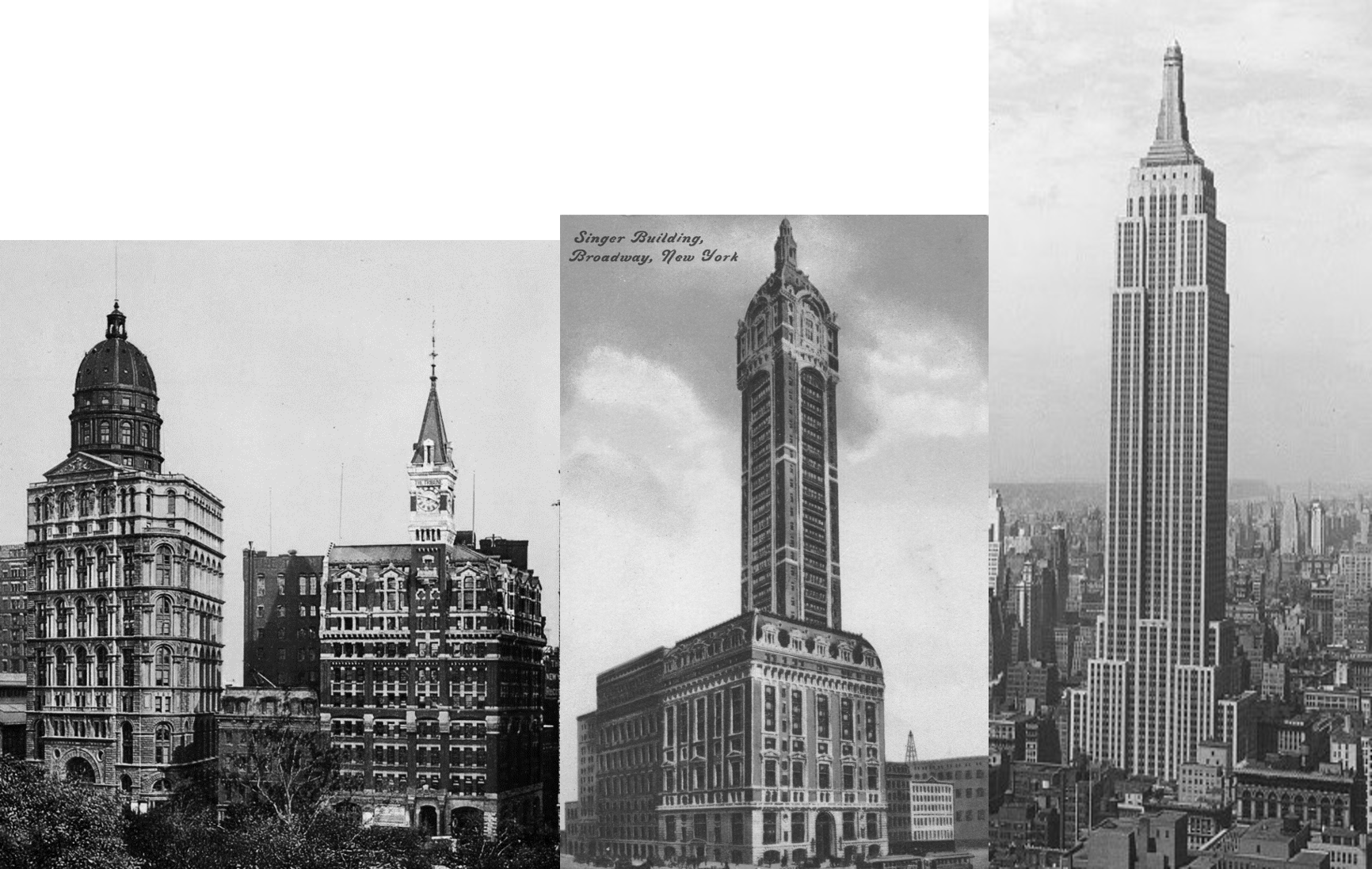

All cities—ancient and new alike—must find the right balance between preserving the past and promoting the future. New York is New York and Dublin is Dublin because, historically speaking, these cities had the flexibility to add housing as the demand arose. Of course, the process was messy and led to a whole suite of building regulations to slow down cities’ ability to change. That is where we are today; the result is an affordability problem. We forget that the historical city was a much more dynamic place, and this dynamism created the magical metropolises we have today. We have nothing to fear but the fear of heights.

Thanks to Maria Thompson for her help with proofreading editing.

—

[1] In the interest of full disclosure, Professor Lyons and I are research collaborators, though he did not work on the research paper discussed in this post. His Tweet was not discussed with me before he posted it. Professor Ronan has no relationship with Johnny Ronan, the developer proposing to build a 45-story tower in Dublin.

[2] Ireland has 4.9 million people, and the Dublin metro area has 1.23 million—nearly 20% of the population. Relative to other European nations, its urbanization rate of 63.41% is relatively low. But given its high income and Dublin’s successful economy, it under-produces tall buildings relative to similar countries.

[3] I also want to be clear that luxury high-rises should not be used by shell corporations to hide or launder money. I have written on this debate here and some policies that can address the negative externalities that might arise from billionaire condo skyscrapers.

[4] When I was in college, my friends and I rented the bottom floor of a large Victorian house near campus. Legend had it that was occupied by Vladimir Nabokov when he was teaching at Cornell. The top floor was converted to a separate two-bedroom apartment. All told, that house was able to comfortably accommodate at least six college students (and their dating partners). Today, such a conversion would be illegal in many cities and would mean that a small household living there would need to keep otherwise usable space unoccupied because the law requires it.