Jason M. Barr March 13, 2019

Almost none of the land use regulations that cities have ardently adopted for over a century have been justified by any serious quantitative work. The existence of even the smallest externality, such as a shadow, has been seen as justification for massive interventions in the housing market. – Edward Glaeser

The sun is the mother of life. Humans, like all biological lifeforms, need sunlight to survive and thrive. From it, they extract vitamin D; warmth for their furless bodies; and a general sense of well-being. Sunlight, however, is a scarce commodity; and even more so in the modern city. And as such, cities produce something of a paradox: we create them to satisfy our needs and wants—to provide jobs, housing, access to amenities, etc.—and, in the process, they generate some undesired outcomes or externalities. There is no free lunch in the urban world. One person’s “agglomeration economies” is another person’s traffic congestion. One woman’s fabulous views are another one’s shadows. One man’s trumpet makes music; to another it makes noise. And so on.

The ultimate—and age-old question—is: how do we create efficient cities—ones that provide the maximum flexibility and benefit, while minimizing the negative externalities?

The Dark Side

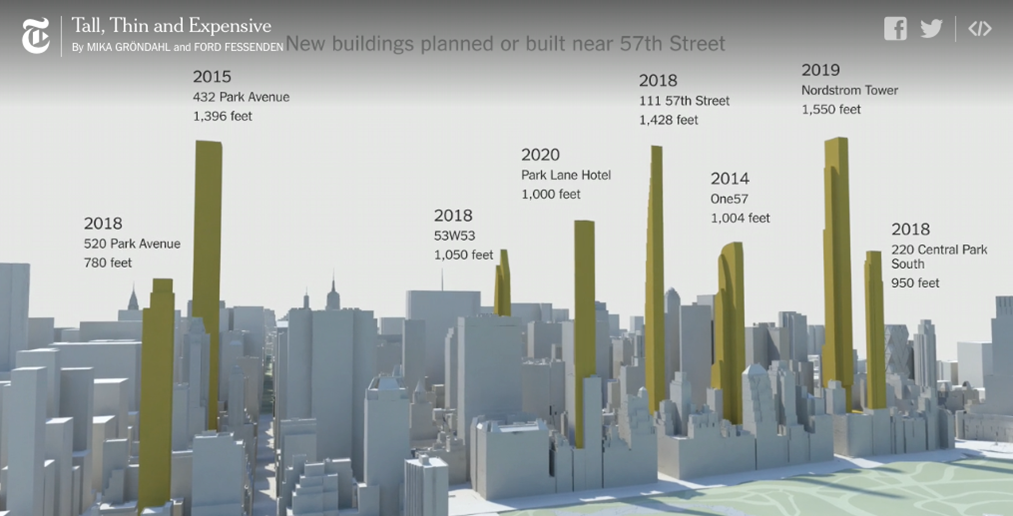

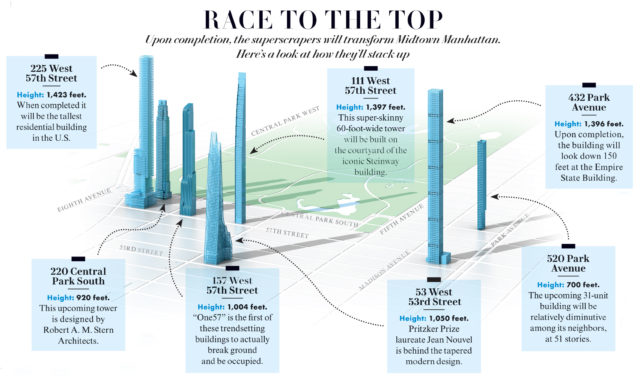

Today, one of the biggest controversies in the real estate world is the construction of superslim, supertall towers around New York’s Central Park. It seems that when one is announced there is an instant knee-jerk reaction against it. Critics present a laundry list of reasons about why they are “bad.” One item that dominates is that of the shadows they are likely to cause. Graphics of their effects on Central Park exacerbate the perceptions of darkness, by giving snap-shop depictions of the longest shadows likely to be cast at any time.

But are city shadows all bad? The answer is no, as they can provide both costs and benefits, which need to be fully measured and understood before we can draw conclusions and consider policies that are directly aimed at limiting real estate in the name of the almighty sun.

The Good

Why might shadows be good? First, is that in hot summers, shadows provide shade, not just to the people who are walking around, but also for the neighborhood to protect against the heat island effect. Plus, shadows can reduce electricity bills from air conditioning.

In Manhattan, real estate brokers try to peddle north-facing apartments—which get less sunlight—as the exposure allegedly preferred by painters, who apparently need softer, indirect light for creating their masterpieces. Residents in south-facing units—with less shade—are subject to oven-like temperatures from the direct beams of the sun.[1] Sunlight reflecting off buildings can become “death rays,” attacking the random pedestrian (arguably, the exact opposite of the shadows problem).

Finally, a building in a shadow might be more affordable to someone who would prefer living in the central city near employment opportunities rather than paying for a higher cost, sunnier unit. Access to sunlight might not be all that important to someone who spends most of the day away from home.

The Bad

But, of course, people, in general, enjoy access to sunlight. It seems to have a calming effect and improve mood and health. Companies prefer locating in glass box skyscrapers because their workers like sunnier offices with more natural light. Shadows might also hamper the ability of trees and plants to grow and can block light on rooftops that might otherwise be useful for solar panels. Shadows on the streets may increase the likelihood of crime and may, more broadly, diminish the quality of urban life. In cold winter months, shadows can increase heating costs.

The Ugly

But perhaps the key problem of shadows is that there is little understanding of their true impacts throughout the day and year. Shadows in the peak of the summer can be helpful for cooling and energy costs, while perhaps can negatively affect moods or well-being. During cold winter, shadows can make the city colder and require more heating, but don’t affect people on the street as much because it’s too cold to spend much time outdoors. And throughout the day, the sun’s position in the sky is changing; one person’s shadow in the morning becomes clear sunshine in the afternoon and vice versa for someone else.

In essence, the shadows problem is quite complex with its impacts on individuals varying throughout the day, the season, the climate, the topography, the location within the city and across the planet, and based on the nature of the built environment.

The Emerging Science of Shadowology

Until recently there have been very few, if any, systematic measurements of the amount of shadows and their impacts. Rather their effects on the city have been left to our imaginations or to simple snap-shot representations. But this is starting to change. Thanks to advances in data collection and computer science, the ability to measure the quantity of shadows in cities is, so to speak, coming out of the shadows. If we can measure the degree of “shadowification,” we can then see how it correlates with well-being and other important variables.

Shadow Accrual Maps

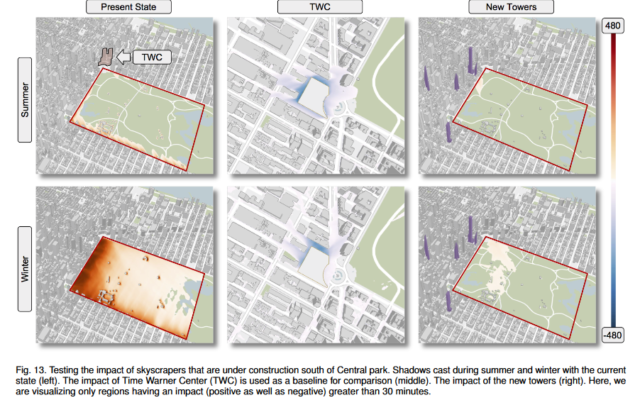

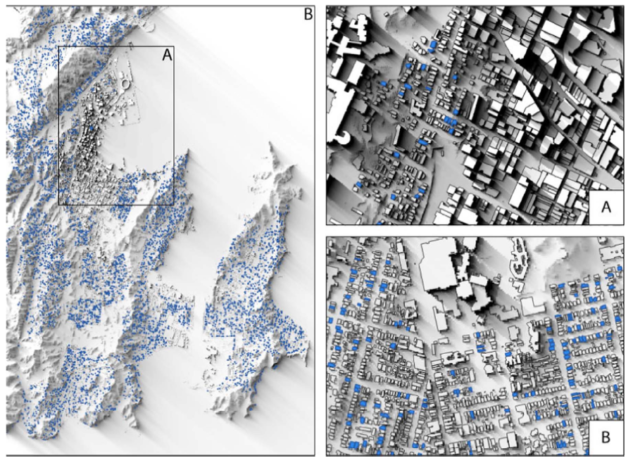

A recent paper by a team of computer scientists attempts to get closer to comprehensive measurement of shadows throughout the day and across the city. “Shadow Accrual Maps: Efficient Accumulation of City-Scale Shadows over Time” (2018), by Miranda et al,. presents newly-developed algorithms to measure the total accrual of shadows using computationally efficient methods. Part of the analysis includes creating net shadow scores, which include both the positive and negative effects.

So what do they find? Using Manhattan as their case study, they analyze the new superslim buildings rising along Central Park South. They find that the total contribution of these structure is relatively modest. They write,

We see that these shadows behave as expected – a lower angle of the sun in winter causes shadows to cover the entire analysis area, while a higher angle in summer results in a tighter shadow area. Note that even though buildings, whether tall or short, cast long shadows at low sun angles (mornings and evenings), its contribution to the overall accumulation is small as reflected in the visualization (p. 10).

Again, it’s worth stressing that the shadows that would fall on Central Park from these new structures is the worst in the winter afternoons, the very time when the park is least likely to be used. Furthermore, when they compare the slim towers to hypothetical alternatives of shorter but bulkier versions, they find that the latter have a greater negative impact than the former.

What’s a Shadow Worth?

But given the ability to generate more precise shadow maps, this begs the question: what’s the cost to city dwellers? For this, we need to look at the net effect of shadows on things that we care about, such as happiness or the value of real estate. To this end, a recent study, called, “Valuing Sunshine,” provides some first estimates to this question. In particular, the authors measured the average number of hours of sunshlight that fall on some 5,000 houses in Wellington, New Zealand. They then investigated the relationship between average hours of annual sunlight and housing prices, controlling for a host of other things that might determine the value of the property, including the views.

The key problem to measurement here is that, ideally, all non-sun-related factors need to be held constant or controlled for, while variation in sunlight access across the city should be as large as possible, in other to better separate out the signal from the noise, as it were.

Ceteris Paribus

Their focus on Wellington to isolate a pure “sunlight effect” had advantages. First, the city is small, and homes are relatively homogeneous, which helps reduce some sources of variation which might mask or confound the sun’s impact. Second, Wellington’s economy and housing market has been relatively stable over the last decade or so—again, reducing noise in measurement that might have come from the global bubble and collapse in the 2000s.

Third, Wellington’s climate is rather moderate. In summer, its average maximum temperature hits only 69°F (20.5°C), while in winter, the maximum average temperature is 52°F (11.1°C). This helps diminish the effect of shadows on energy costs. Lastly, the geographical topography of the city contains several hills and valleys, creating large variation in sunlight exposure for the houses in the sample. As the authors say, “Thus, it is not difficult to find houses that, located in the same narrowly defined neighborhood, have very different exposure to direct sunlight due to the effects of hills, valleys and nearby buildings” (p 270).

In short, they find that, on average, a house that receives an extra hour of sunlight per day throughout the year has a 2.6% higher price. For the average house in Wellington that additional hour of sunlight is worth about $NZ16,000 ($US11,000).[2] Or, on the flipside, a neighbor who is suddenly put in shadows for an extra hour per day due to a new building next door can expect to lose about 2.6% of the value of the house, on average.

Policies for the Shadows Problem

The Pigouvian Tax

Given the ability to measure the total additional hours of shadows from new construction, it seems a relatively straightforward exercise to “plug in” the shape of a proposed structure and estimate the average reduction in sunlight per hour per day on surrounding buildings and parks. Then a Pigouvian tax could be imposed of say 2.6% of the market value of the structure for each lost hour of direct sun (again an actual tax value would need to be determined from more research). If the levy is worth it to the developer, he goes ahead with the project, pays the tax, and the money is disturbed to the harmed parties. If not, he has the option to redesign the project to reduce the shadows and the tax. This policy has the advantage of being relatively simple and straightforward, and the tax burden will fall heavier on those building taller or bulkier structures.

But what’s to be done with the tax money given to owners of a park (the City)? Here the government would need to come up with ways to improve the quality of parks to offset the loss in user-value; this might come from adding trees or other amenities within the parks, or by providing more green space elsewhere in the neighborhood.

Market Value Insurance

The problem with the tax, however, (aside from the fact that it might be hard sell within today’s political climate) is that new construction provides both costs and benefits to surrounding properties. On one hand, it might increase foot traffic to stores or improve the general desirability of the areas and thus raise land values. On the other hand, it might create more traffic congestion, noise, and shadows.

This create something of a problem for Pigovan taxes in the city, since there are many negative externalities that would have to be taxed, while at the same time the positive externalities should be subsidized. What’s the right tax policy? Unlike, say a carbon tax on property owners to reduce C02 emissions, in case of new construction, the right policy is less clear.

A more generalized and easier-to-implement policy might be some form of market value insurance. The idea is that property owners pay a small annual premium against the loss of value to their properties due to changes in the value of the neighborhood itself or due to the actions of neighbors (and not due to market fluctuations or the actions of the owner). The point is that in a dynamic, growing city, new construction is necessary and inevitable, and can have both positive and negative effects on the surrounding structures. If owners had some means of being compensated, those harmed by shadows will get their due, and will hopefully avoid employing the NIMBYism that seeks to stop the city dead in its tracks.[3]

Seeing the Light?

The problem of city shadows perfectly illustrates the paradox of cities: they are both the solution to, and cause of, many problems with which humans must contend. But fundamentally cities are engines of growth and well-being. In the 21st century, large metropolises, like New York, are increasingly important in our lives. But who gets to define what they will look like in the 21st century–those who want to keep it in a form a status, or those who want to accommodate all who want to call it home?

The success of humanity over the long run has always been based in fostering increased trade and human interactions. The key to the efficient—well-functioning city—is to identify the negative externalities that arise from dense living and devise policies that alter the incentives to better balance the good with the bad. Simply saying “no” to growth and change may feel right, but in the long run, its rarely been a winning policy. Let’s not be afraid of our own shadows.

—

[1] Manhattan is an interesting case-study in regard to the direction of its streets. In 1811, the Grid Plan Commissioners created blocks in an east-west direction, orthogonal to the two rivers (and no one really knows why). This had the effect of creating a kind of two-tired city. South-facing units get direct access to the sun. North-facing units do not. Throughout the rest of the city, housing units have more variation in their directionality and access to sunlight. (It seems there’s an economics paper to be written here by looking at how the block directions in the various boroughs affect access to sunlight and how that might affect housing prices. Contact me if you want to work on this project. GIS skills are a must.)

[2] Their sample includes transactions from 2008 – 2014. During this time, the average exchange rate was 1NZD = 0.76USD. Today the rate is 1NZD=0.68USD. Also note, the average house in their sample gets 6.7 hours of sunlight in winter and 10.7 hours in summer.

[3] A city might also consider a Pigovian tax for shadows just in parks, especially if the units remain empty for much of the year.