Jason M. Barr December 27, 2022

Slouching Towards Utopia is a “grand narrative” of the “long 20th century” from 1870 to 2010. It focuses on the economic and political evolution of the global north, particularly Western Europe until the end of World War II, and the United States since then. The unifying theme is that Western world history can be understood by the evolution of technology, free markets, globalization, and the ability of governments to deal with them (or not).

Our Tour Guides

On the tour, however, we are not alone. Holding our right hand is the free marketeer Austrian economist Friedrich August von Hayek (1899-1992). Holding our left hand is the moral philosopher and socialist thinker Karl Polanyi (1886-1964). As we walk through history, each whispers in our ears about how to make sense of what we see.

Hayek tells us that the mistakes of history emerge from government overreach. In attempts to correct the market’s dislocations, officials made the problems worse. Socialism and Fascism were master projects designed to intervene to the benefit of some, but they led to “serfdom” for all. Governments, he argues, cannot micromanage our economy without micromanaging our lives. Planning and totalitarianism are just two sides of the same coin.

Karly Polanyi says, “nuts to that!” The state is here to guard what we hold dear, such as fairness, stability, dignity, and social connectivity. While the market can help us, the government must do what the market cannot. DeLong, paraphrasing Jesus, summarizes Polanyi’s position that the “market was made for man, not man for the market.” (This puts Hayek in the role of the Gospel’s Pharisees.)

Polanyi points to the rise and collapse of the Gold Standard and the Great Depression as to why capitalism cannot be left to its own devices. The market’s seeming quest for efficiency ultimately leads to instability and dehumanization.

Heroes and Villains

And so, with Professor DeLong at the lead, and Polanyi and Hayek by our sides, we stroll through the major events in Western political economics. DeLong’s hero is John Maynard Keynes. In his 1919 book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, he rightly scolded the Allied Powers after World War I for their rapaciousness and vindictiveness. In his 1936 classic, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, he showed why depressions might not automatically self-correct to boom times. He offered useful advice on how governments can right the economic ship through “Keynesian” spending programs.

After World War II, at the Bretton Woods Conference, he helped construct the modern economic order, which not only created the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank but also established the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve as the world’s de facto central bank.

By the 1950s, Keynesian economics, in one form or another, was deeply embedded in Western economic thinking and policy. Keynes thus becomes the modern Jesus—the man who points us to the economic kingdom come.

The story’s villain is Keynes’ arch nemesis, Inflation (or extreme changes in currency values more broadly, including deflation). Inflation robs us of our ability to predict the future and measure value; it’s the insidious devil in our midst. And when governments print money for their own ends, it leads only to dystopia. Or, as Keynes has put it, “There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

Attempts to control it using the Gold Standard led us to World War I. The “quick fix” of printing money ultimately led to World War II. The Stagflation of the 1970s led to the triumph of Neoliberalism, which has generated unchecked income inequality, lower economic growth, and renewed social divisions.

The Long 20th Century

DeLong divides the “Long 20th Century” into four periods. The first—1870 to 1914—can be called Slouching 1.0. 1914 to 1945 is Dystopia 2.0 (whereas Dystopia 1.0 lasted from time immemorial to 1869). Next is Post-World War II to 1973, a time he calls the “Thirty Glorious Years of Social Democracy,” but can otherwise be called Slouching 2.0. Lastly is 1973 to 2010, the period of the Neoliberal turn, which might be called Supinetopia—neither slouching nor falling, but not standing upright either.

Slouching 1.0

In Period 1, humanity has firmly hitched its wagon to economic growth—or, more specifically, to the suite of institutions and economic endeavors that obliterate the Curse of Malthus, that population expansion will ever exceed caloric production. The key trick was learning how to harness inventions to improve our lives. Western societies developed the right institutions. They created the bureaucratic corporate form of businesses, which developed organized research and development labs. Near-universal education for the masses helped to generate these innovations and spread access to them from rising wages. Governments imposed (or allowed) market orientations to guide the resource allocation problem.

The trifecta of trade, innovation, and governmental economic “liberalism” produced, for the first time in human history, a whiff that material “utopia” was just around the corner.

Dystopia 2.0

However, this period of slouching unwittingly set the seeds for a major setback. The embrace of capitalism generated new uncertainties. The old world, to be sure, had its problems, from kings’ wars to famines and plagues, but being tied to the farm was the one great constant. Peasants had their land, their economic obligations, and their religious rituals. Little changed from decade to decade. But then, agrarian life was swept away by economic tides that no one could stop.

The farmers went off to cities seeking work, and in exchange, they gained uncertainty and exploitation. Not quite knowing what to do, governments groped, and often mismanaged, their way through, be it via tariffs, printing money, or gaming the Gold Standard.

Globalization, the rise of the bourgeois, and the absorption of technology into society led the old “balance of power” to collapse. Nationalistic states replaced empires and monarchies and produced total war—entire populations drafted into the effort, either as fighters, factory workers, or propagandists. The end was unimaginable destruction, as each side was stalemated by its stockpiles of industrial death machines.

Ideology

The Industrial Revolution also generated an intellectual flowering of thought that tried to understand what was happening and whether it was “good” or not. And if not, what were the blueprints to utopia? In the marketplace of ideas arose new ideologies—systems of “total belief” that could carry the masses into the Promised Land. If Jesus was a Jewish apocalyptic preacher who told the peasants of Roman Palestine that the Kingdom of God was on its way to righteous believers, then Marx and Engels, Lenin, Mussolini, and Hitler offered their versions of utopian kingdoms provided by the nation-state.

They could only succeed by draining the pools of despair that washed over the masses. Lenin created his version of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, which appropriated private property and distributed it “from each according to their ability; to each according to their need.” To the right of Lenin, but to the left of the “Hayekians,” were the Fascists. They promised utopia by creating a highly socialized economy for the “right” people at the expense of the “inferior other.”

On the economic right—fighting back against totalitarianism—were the disciples of Adam Smith. Smith did not set out to form a new ideology or economic religion. Rather he aimed to loosen the old order created by the “divine right” of kings to form monopolies and subject his people to economic restrictions and wars for his own benefit. But Smith’s disciples in Austria, Britain, and America spread the good news of the Gold Standard and “laisse-faireism.”

World War II was as much a war of ideologies as it was a war of nations.

Rebuilding the House: Slouching 2.0

From the wreckage of 1914 to 1945, the global north got its act together—or rather, the Western democracies demonstrated that the road to utopia was a form of Keynsian-Polanyism. States would intervene to minimize the dislocations of the business cycle and provide a basket of resources that the market would not—unemployment benefits, health insurance, old-age pensions, public goods, scientific research, universal suffrage, and so on.

Thus, the post-war period saw the rise in the democratic “welfare state” as the alternative to totalitarian socialism (or what DeLong calls really-existing socialism). America, left unscathed by the two total wars, replaced the British Empire as an economic and political “hegemon.” Its new role as the great centralizer and stabilizer (and bulwark against the Soviet Union) helped maintain a period of peace, economic stability, and prosperity. And the road to utopia, according to DeLong, was now open.

The Neoliberal Replacement

But then, a series of economic shocks disrupted the bright future. High inflation in the 1960s and the Oil Crises of the 1970s led to Stagflation. But governments were reluctant to raise interest rates lest it reduces the full employment that was now part of the social contract.

The Stagflation problem gave renewed impetus to the Hayekians, whose new prophet was Milton Friedman. He argued the state had no business trying to micromanage or “fine-tune” the economy, as the “cure” was often worse than the disease. Simultaneously, and almost by accident, Paul Volker was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve, and his mandate was clear: spike interest rates to “bleed” inflation out of the economy. It achieved its purpose but came with great economic pain.

Reaganism

The resurgence of neo-classical economics helped give rise to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who aimed to dismantle the welfare state by slashing taxes on the rich. They sought to win the Cold War through defense spending and arms races (while paying lip service to the need for fiscal austerity).

DeLong argues that the resulting deficit spending jacked up interest rates and created an unnaturally strong dollar. This wiped out American manufacturing, spurring widening income inequality and lower economic growth (the supplysiders never lived up to their hype). The collective response, however, was a shrugging of the shoulders.

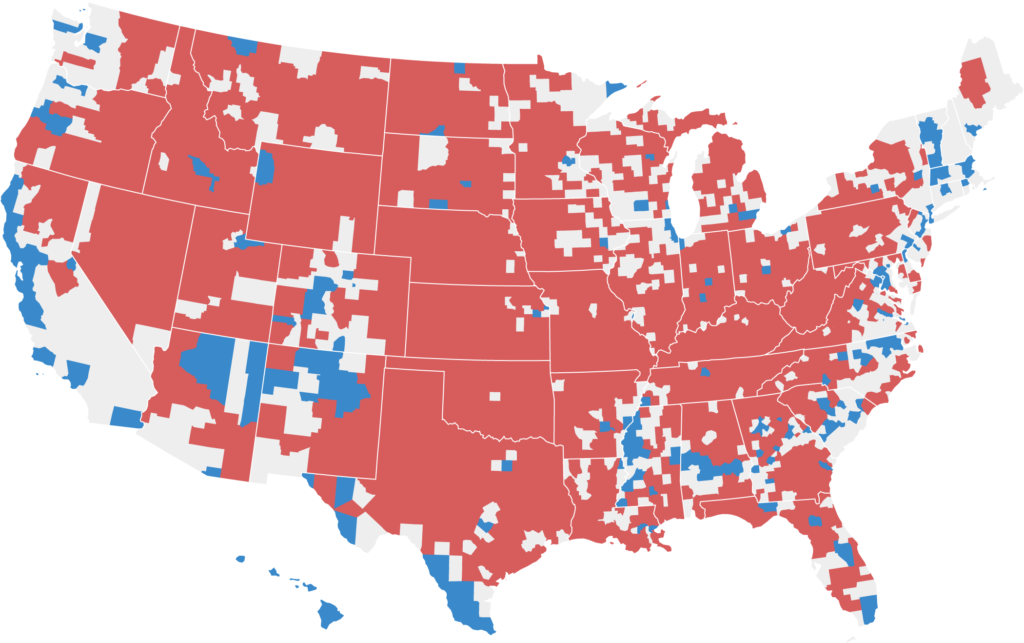

Since the 1970s, the Neoliberal paradigm, which says that “man was made for the market,” has reigned supreme. When the Great Recession came in 2008-09, triggered by a financial crisis of epic proportions, few in power called for rethinking our reliance on the market. Rather governments did what they could to shore up those “too big to fail,” pumped liquidity into the system, and produced a Keynesian stimulus package to comfort workers. But when the tsunami finally passed—after nearly a decade—it was all but forgotten. In its wake was the rise of Trumpism and a new period of division and uncertainty.

The book thus ends on a pessimistic note. After World War II, we had utopia in our grasp, but we let it slip away because we were too hypnotized by the Siren song of the free market.

The Grand Narrative

As a grand narrative, the book is well-written, well-researched, and enjoyable to read. But what are we to make of it as a contribution? An important book should either be a story or an argument. It should delve deeply into either the whats of history or the whys. It is here that Slouching struggles to find its path. As a 500-plus-page book on 140 years of the success and failures of modernization, it attempts to do both things at once and yet does not quite succeed in either. It’s too grand by half.

In telling the big story—both intellectually and historically—the book is neither broad enough nor specific enough. It leaves the reader feeling a little alienated from the deeper meaning and trajectory of our material existence. Providing both an array of small (but interesting) details and large brushstrokes, the narrative slides quickly through the main changes in human history: the budding shoots of innovation, markets, and global trade; the drastic reversal in the first half of the 20th century; the battle between socialism and capitalism; the “winning of the West”; and finally, the Neoliberal turn.

Along the way, it travels from the Global North to the Global South and spends a spell in China, Japan, and the Soviet Union. It breezes through the rise of Civil Rights in America and abroad (yet DeLong spends nearly 30 pages on Hitler’s war strategy).

I wish it had either gone up—into a bigger but briefer unifying picture—or down into a few key detailed strands. Overall, it reads like we are watching Dancing with the Stars featuring the 20th century’s Great Leaders and Economic Thinkers. Think of Hayek tangoing with Polanyi and then Hitler waltzing with Churchill. The show is mesmerizing to watch because we don’t know who might fall or who might pirouette with sublime elan, but overall it’s not as satisfying as an opera or ballet.

What is Utopia?

The epithet, “slouching towards utopia,” summarizes DeLong’s argument that we have embraced trade and globalization, technological innovation, and “safety net” republican democracies because we believe they will move us that much closer to utopia itself. However, DeLong does not give us a precise definition of his version. And as the cliché goes, the word “utopia” means both “no place” and “the good place”—the location of perfection. There’s hardly a consensus on what this ideal place might be and whether it can actually be created.

The two “Golden Ages” of the West (Slouching 1.0 and 2.0)—if we can in fact call them that—were significant steps forward, but it seems a stretch to say that they laid a path for possible utopia or helped wipe away the vast suite of human indignities and tragedies. Yes, we can achieve economic growth and material prosperity; and, yes, we can reduce the vagaries of the market through government interventions, but can we truly make humanity happy and wholly satisfied with life?

If so, it’s hardly clear how governments can achieve this. If recent history is any guide (be it Trumpism; our slavish attachment to social media, iPhones, and AI; Brexit; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s threat to invade Taiwan, etc.), we still don’t even know what we are looking for in terms of the Promised Land.

Is it Finland?

From what one can infer, the “utopian model” for DeLong is present-day Finland—a democratic market-oriented nation-state with large government involvement in the economy. If surveys are to be believed, Finland is indeed the happiest place on Earth. But I’m sure it’s news to the Finns that they have achieved utopia.

And if it is a utopia, it might just be for them. How can we replicate such a thing across the planet, where each country has its own history, institutions, cultures, political objectives and requirements, and notions of the good life, and where nationalism all too easily slips into hatred and “otherism”? (Not for nothing, the Finns joined NATO for this reason.)

The Gales of Destruction

The paradox of utopia is that it can only happen in a world where the rug is not constantly being pulled out from beneath us. But the quest to achieve material Peace on Earth requires constant change. As Joseph Schumpeter has pointed out, economic growth, by its very nature, forces us to be ever hit by the economic gales (and occasional hurricanes) of creative destruction.

Our current world of slow growth exposes the utopian contradictions of capitalism: even with material prosperity at hand, low growth rates create “idle hands,” which are used to divide and cast blame on the “other.” Yet to get back to rapid growth to achieve full employment requires intense industrial competition and constant innovation. Growth has to be so rapid to not only absorb the newly minted adults but also to re-employ those who are victims of the incessant industrial restructuring. In the developed world, it seems this might be a near-impossible task.

It’s also easy to see how constant change can make us richer, but it’s hard to see how this will make us happier. As the economist Richard Easterlin has pointed out—in what has become known as the Easterlin Paradox—if we are in a perpetual rat race to improve our material position, the average person’s sense of well-being will remain constant since we are always comparing ourselves to those above us in the social and economic ladder. Happiness, it seems, is a zero-sum game.

If the lesson of the 20th century is anything, it’s that no one can agree on exactly what utopia is. How can we be slouching toward it when we don’t even know what it is?

The Role of the Mind?

Utopia is a state of mind, and the quest for it requires us to think more deeply about the role of the mind in the evolution of economic history. DeLong rightly focuses on the important economic theorists of the long 20th century. He is to be commended for his attempt to weave history, economics, and ideas into a grand narrative.

The devastating ideologies of the 20th century—be it Socialism or Fascism—were smacked onto the world because aggressive and ambitious leaders believed that they were good ideas, at least for them. They sold ideologies that filled an emotional void first and then they ran their economies on the fly accordingly.

Let us not forget that Marx published The Communist Manifesto nearly two decades before he provided his economic theory in Das Kapital for the supposedly inevitable proletarian takeover. Never mind that Lenin decided it was better to take matters into his own hands and foment revolution rather than wait for the inevitable to emerge eventually. For that matter, Adam Smith provided intellectual cover for the British navy to create colonies, client states, and treaty ports.

Modern Gospels

One of the implicit themes of the book is that we can use the Gospels as a metaphor about how to think about the 20th century. Jesus’s sayings were, in part, about creating a new religion—a new overarching utopia for humanity. But this religion was replaced in the 20th century with state-sponsored ideology. The quest for utopia fell apart because ideology was not made for man, as it were. In its wake, we have modern capitalism, a paradoxical ideology of the negative, which says that we must wholeheartedly believe that every other ideology about the market is wrong.

The point is that economic theory—both descriptive and mathematical—is essentially just a justification for what people want to see in society.[1] There never was value-free economics. The ideological economists of the 20th century wore it on their sleeves. Perhaps the key value of DeLong’s book is to show that throughout history, religion. and economic theory were often two sides of the same coin, and we need to think more deeply about how our beliefs, perceptions, imaginings, and ideas are just as important, if not more so, than the dry equations of profit and utility maximization, and market equilibria. Modern economic theory, after all, is just a story about how we ought to behave as atomistic individuals.

Our history was created from the “dialectic” between those who believed the market was good versus those who did not. Slouching helps us to see that more clearly.

—

[1] Yes, today’s economics is a social science that attempts to adhere to the scientific method, but it’s also important to recognize that the neoclassical theories of utility and profit maximization are implicitly ideas about how to achieve a version of economic utopia: if an economy maximized total utility and total profits, we’d be living in economic paradise.