Jason M. Barr February 21, 2022

Surely, in the light of history, it is more intelligent to hope rather than to fear, to try rather than not to try. For one thing we know beyond all doubt: Nothing has ever been achieved by the person who says, ‘It can’t be done.’ – Eleanor Roosevelt

Jason Breaks the Internet

On January 14, 2022, I, Jason M. Barr, broke the internet.

Narrator voice over: “He did not break the internet.”

Well, okay, maybe that’s true. But on that day, the New York Times published my guest opinion piece, “1,760 Acres. That’s How Much More of Manhattan We Need.” The internet commentariat went amok.

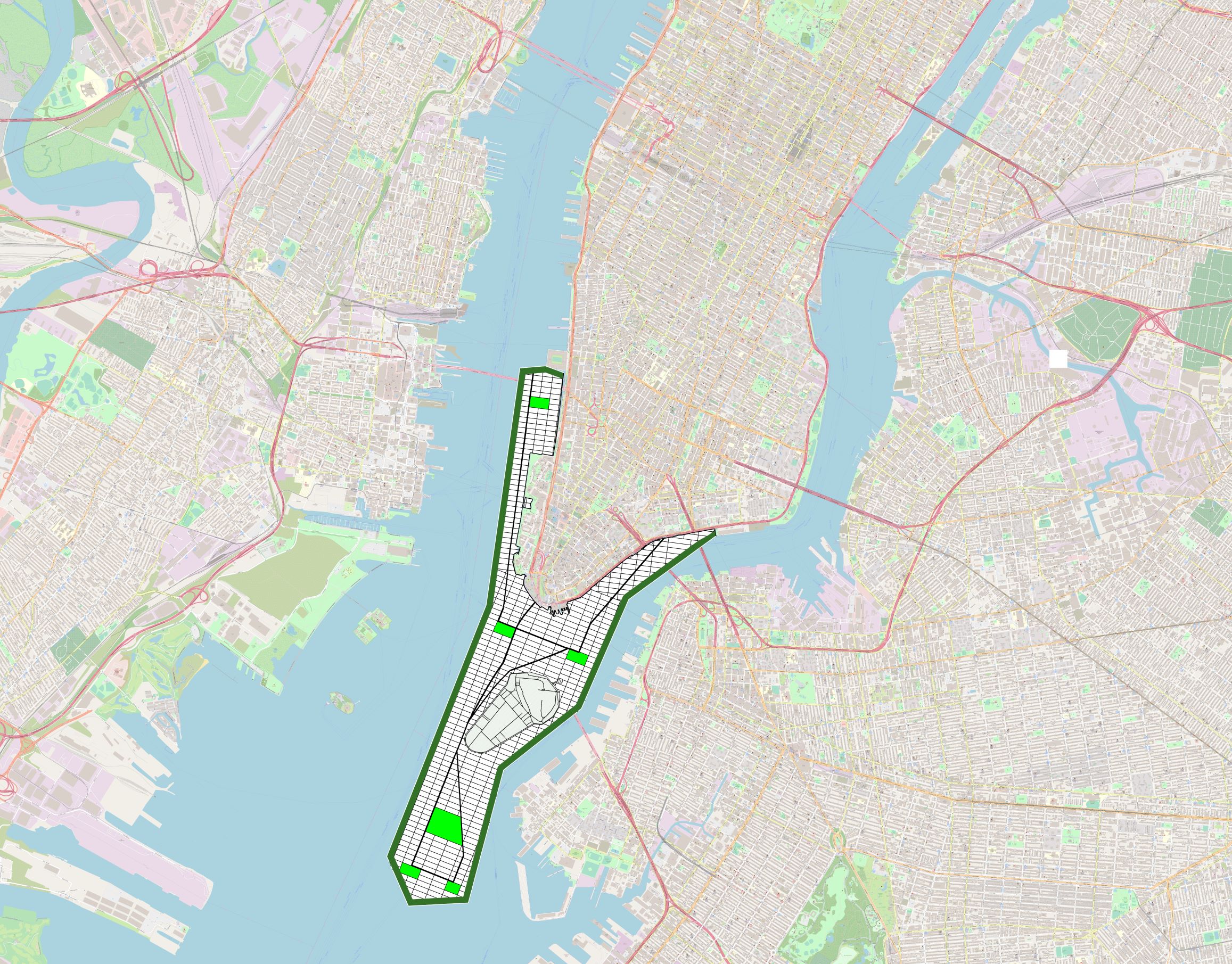

The piece offered a plan to expand the island of Manhattan 2.5 miles (4 km) into New York harbor to serve two purposes at once: protect Lower Manhattan from climate-change-induced storm surges and sea-level rise and to build much-needed housing. Since Manhattan land is the most expensive real estate on the planet, leveraging this value could assist the common good. The leases or sales from the new land would more than pay for the costs of creating it (see below), producing income for other programs and improvements.

And with such a large amount of new urban space, we could recreate from scratch a vibrant, diverse neighborhood for an additional 250,000 New Yorkers. The shorelines would be built with wetlands, beaches, and berms to absorb surges, and the rest of the built-up areas would be constructed at a higher elevation to keep it protected. In the process, lower Manhattan, the heart and lifeline of New York’s $1.7 trillion economy, would also be protected.

The Medium Was the Message

The plan became instant news, which produced a host of ironies that I will discuss throughout this post. But the biggest one was that if I had simply posted this idea on my Skynomics Blog, like this piece here, it would have caused barely a rumple in the space-time continuum. However, having the imprimatur of the New York Times, who accepted my proposal as worthy of being launched into the public forum, meant that the medium became the message. The act of printing the proposal became the news.

The week following its release, I was interviewed on local WPIX news, Cheddar, Voice of America, and a handful of other outlets. The proposal was covered by the Daily Mail, the New York Post, Curbed.com, and Dezeen. To one outlet, the plan was “buzzy,” to another it was “galaxy-brained,” while to yet another it was “pharaonic,” and to one, it was just plain “loco.” Alas, if the reactions taught me anything, it is that proposing big ideas in the 21st century has become, let’s just say, impolite.

Since the Times is valuable real estate, I was required by editorial demands to keep my piece below 800 words. I now present more details along with some rebuttals to the “it-can’t-or-shouldn’t-be-done” constituency. So, dear reader, come with me on a journey about how it all unfolded and where we can go next.

Jason Interviews Jason

During the press interviews, the questions tended to be the same: How did I come up with this idea and what was the reaction?

How the Idea Sprang Into My Head?

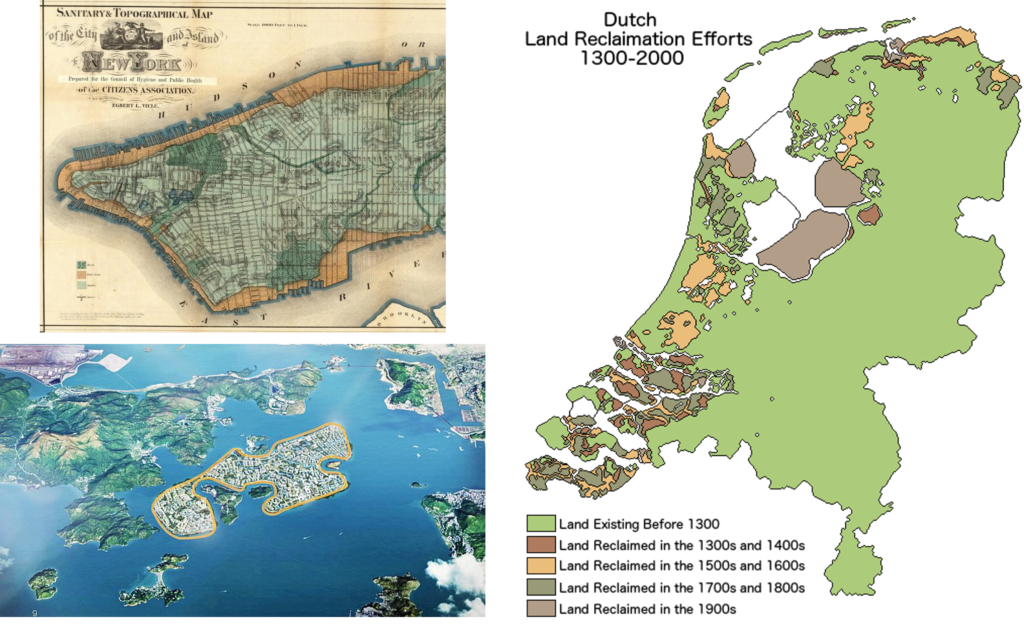

The idea emerged in 2013 as I was researching my book, Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth and Manhattan’s Skyscrapers. During that time, I came to see how from the Dutch colonial days to the present, Manhattan has been, in fits and starts, expanding its shoreline. When the Dutch settled along the island’s lower tip, they encountered lowlands like that from home. They built canals to drain the marshlands and erected retaining walls along the shorelines to fill in with new land to facilitate trade and commerce.

When the English took over in 1664, they continued making more land. In this case, they demarcated property lines extending out to the rivers where the riverbed was exposed during low tide. These “water lots” were auctioned off, and the buyers were responsible for filling them in and making them level with the street grade. The expanded shoreline was helpful for trade since ships could dock in wharves along the streets, even at low tide.

Manhattan’s expansion continued for decades so that by 1865, the lower tip of Manhattan was some 30% bigger than it had been before. It created valuable real estate and parks to help the city grow and remain vibrant. In the 1970s, the city’s last major landfill project, Battery Park City, was created from the excavated material from the World Trade Center site.

Superstorm Sandy

When I was writing my book, I was also researching the impact of Superstorm Sandy on New York real estate prices. When I viewed the surge map, I noticed that Battery Park City was largely spared from the flooding. About that time, Mayor Bloomberg also proposed in-fill and housing along the East River, which he called Seaport City, based on the Battery Park City model. It never got off the drawing board.

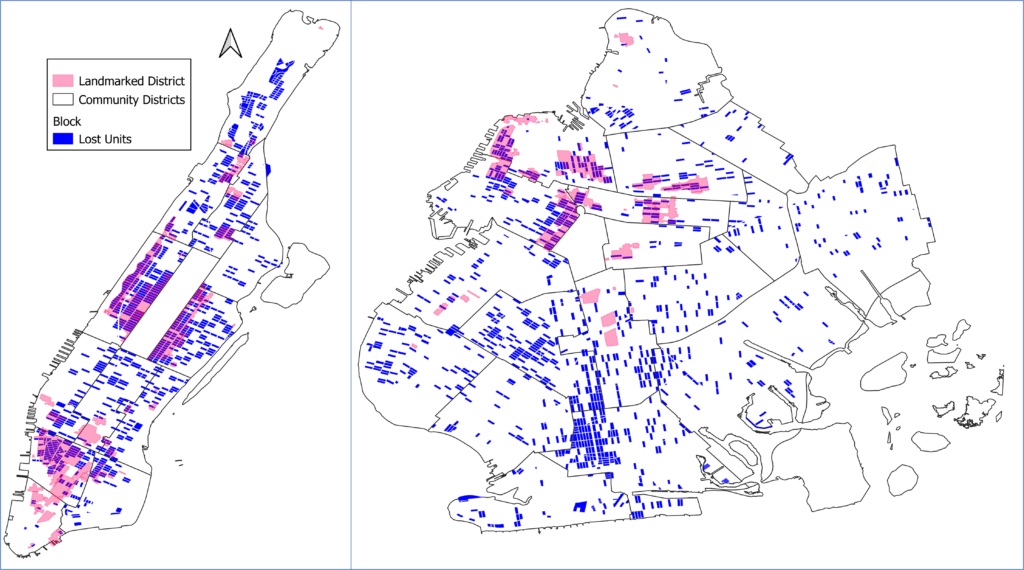

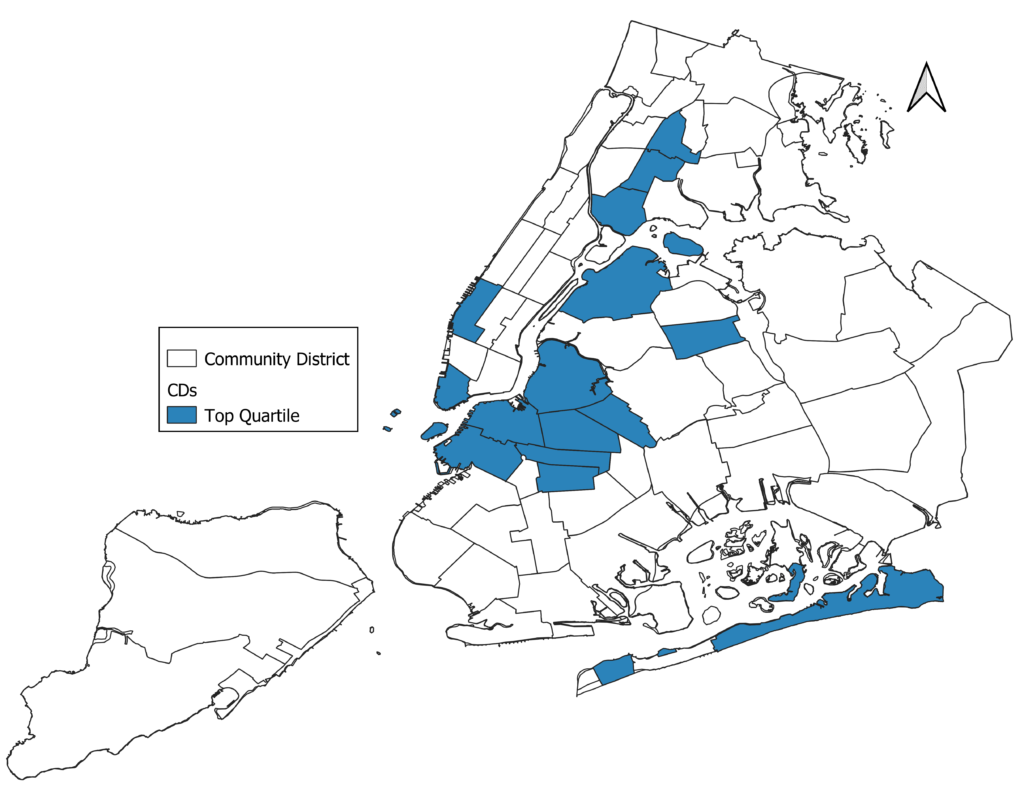

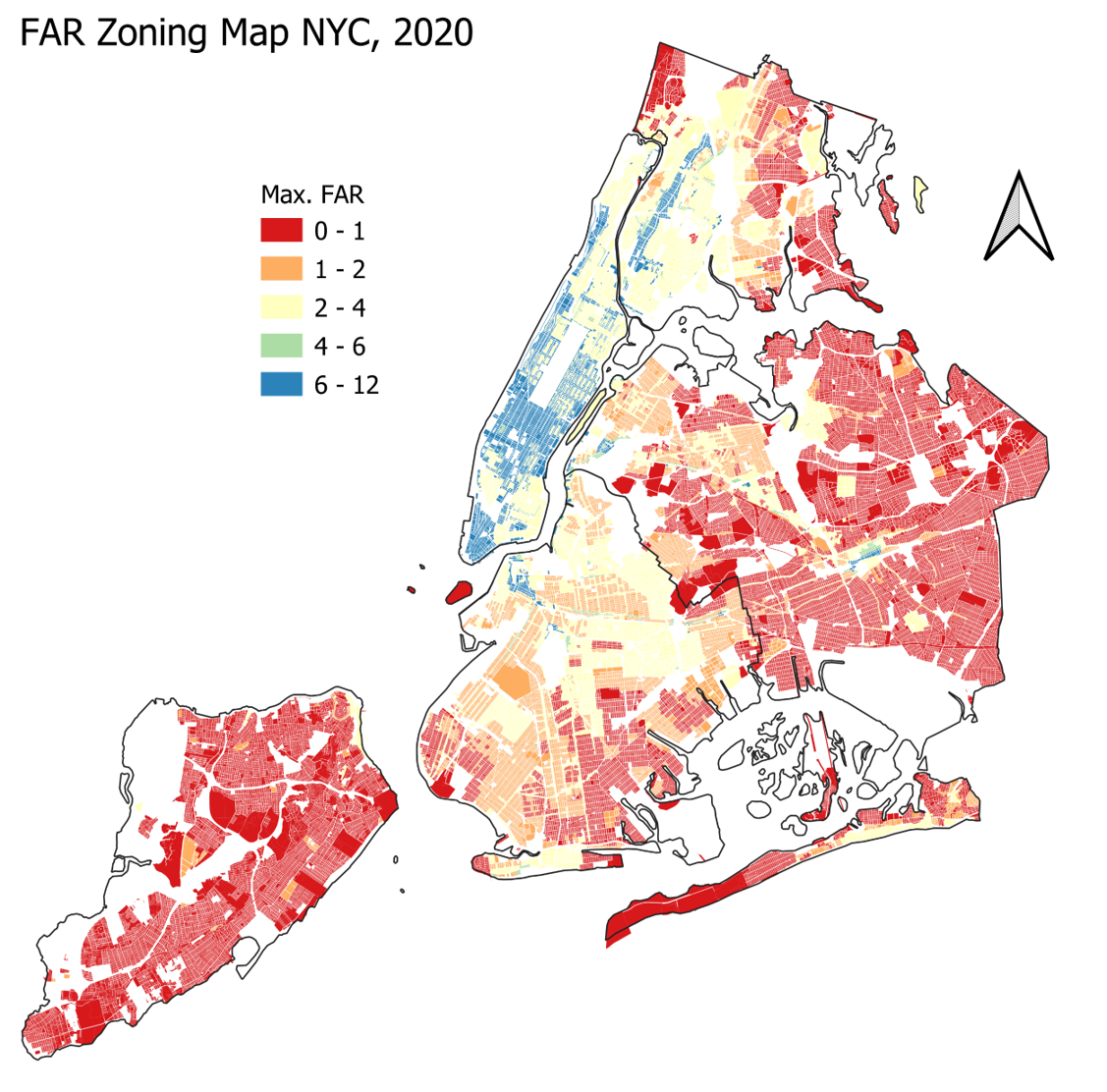

However, as I thought about it, New York also suffers from a housing shortage. Housing prices keep rising because the demand to live in New York outstrips its ability to supply new housing, especially for the middle- and lower-income groups. As I have documented in other posts, many parts of New York are essentially closed to building large amounts of much-needed housing. The new housing that is built tends to be in a handful of neighborhoods, primarily in gentrifying areas, where the demand keeps prices high. In essence, New York has painted itself into a housing corner.

With this in mind, I created a plan that goes big—that not only protects the city from flooding but can also make a dent in the housing market and help the city well into the 21st century. My idea, in short, was to do a larger version of what New York has been doing for centuries. Going forward, we will spend billions on climate change mitigation; we must build more housing; and we must protect lower Manhattan. I asked myself: Is there a way to do these things more efficiently and get a return on the investment? My answer: build out Manhattan 1760 acres into the harbor.

What Surprised Me About the Reactions?

The reactions to my proposal were bifurcated: people either loved it or rejected it outright. (Also, I have not heard from the Adams administration, and I have no idea what the mayor or his aides think). I was pleasantly surprised by the number of people who appreciated its big-scale aspect. Like me, many others are frustrated by the pessimism pervading our beliefs regarding government and society to think creatively and boldly about solving the problems we face. I also learned that my plan put me in the company of those who view sea-level rise as one of our most significant national security problems.

Regarding the negativity, I know that social media trains people in Pavlovian fashion to respond in the opposite direction of a post. If Person A, Tweets “X,” then a thousand people respond with “Y.” Again, the medium is the message. Social media, which also includes online newspapers like the New York Times, amplifies our tendencies to be contradictory for the sake of being contradictory. That just comes with the territory.

Radical?

But arguably, my biggest surprise was to hear that my proposal was considered radical and even outlandish. Yes, it’s big and ballsy, but it’s an extension, literally and figuratively, of something that New York has been doing for 400 years. And just as importantly, it’s being done worldwide, right now, as you read this.

Other big cities have land shortages and coastal problems, and they are taking action. We, on the other hand, are mired in our perverse fantasies that “it can’t or shouldn’t be done.” Our lack of interest in keeping abreast of what’s going on globally helps feed our collective sense that inaction is the best way forward.

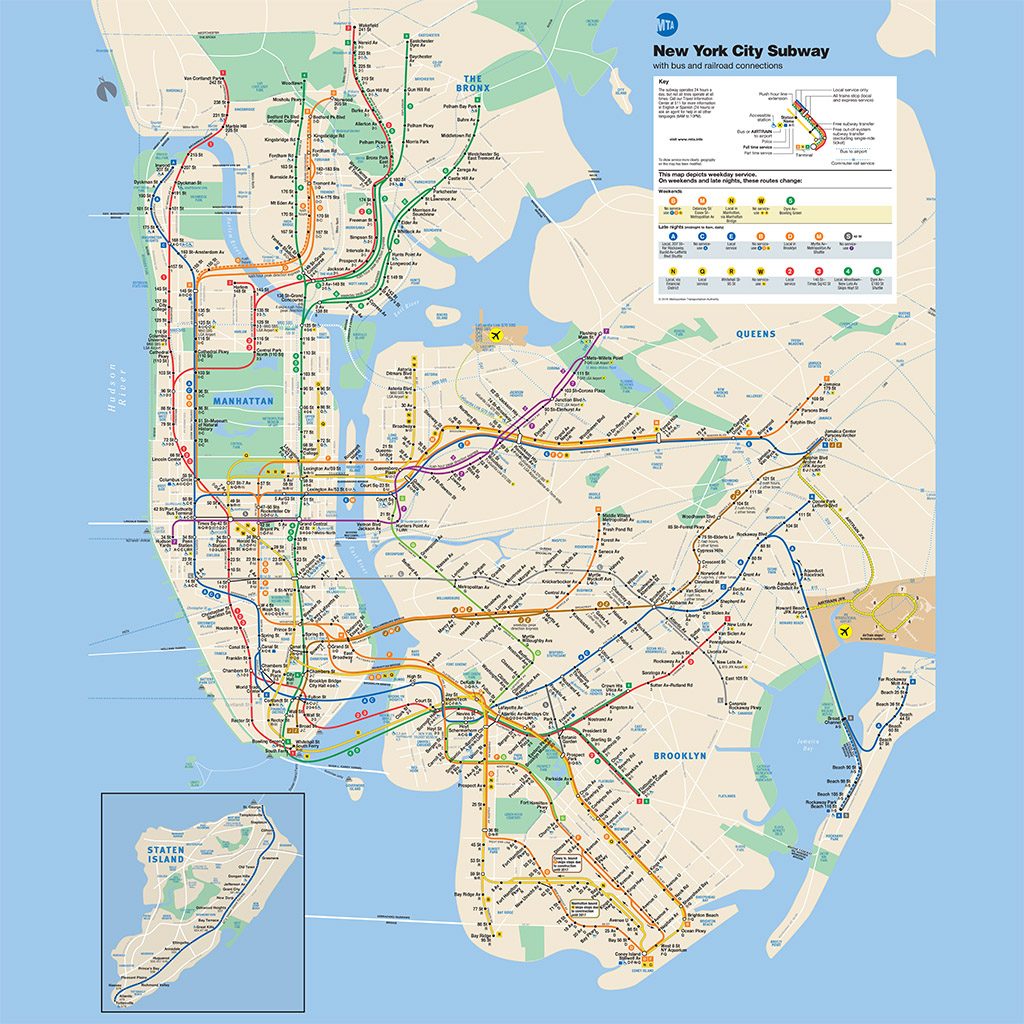

New York helped invent the megaproject in the 19th and 20th centuries—be it the Croton Aqueduct, the subway system, or the Manhattan skyline itself. The embracement of the megaproject made New York City the world’s greatest metropolis, and its lessons were deeply learned across the world, where today mega is ordinary, and where Asian countries are using mega to beat the West at its own game.

Land Reclamation and Shoreline Remediation Around the World

I will not fill this post with the excruciating details of how inaction on coastal flooding will continue to devastate the United States. Rather, I will give a couple of brief examples from around the world, where other countries are not only protecting their coastlines but enabling their cities to grow and thrive.

The Netherlands

The Dutch have made an art of reclamation and shoreline resiliency to protect their country against the sea and create new land for its residents. That my plan could cause such a stir in the U.S. was considered comical to the Dutch on Twitter.

In English, the word “Netherlands” literally means “lowlands” or “under-lands.” According to one study, 65% of the country would otherwise be underwater at high tide if not for the dikes, dunes, and pumps. Land reclamation in the 20th century has added 637 square miles (1,650 km2; 165,000 hectares) to the country’s land area.

Today the Dutch are bravely dealing with climate change; they have strategies that include building beaches, shorelines, and canals to absorb floods. My plan not only allows for this but provides a way to pay for it. Sure, there are criticisms of past Dutch practices, but when a country is literally underwater, its projects are worth exploring for our own use or adaptation.

Hong Kong

Arguably, Hong Kong is the Asian master of land reclamation. When the British seized control of Hong Kong Island in 1841, they realized that there was relatively little land. Most of the city is rugged mountains with valuable strips along the coast. Officials auctioned off “water lots” to merchants early in its history, extending the island into Victoria Harbor. The practice has continued now for nearly two centuries. Today, about 6% of Hong Kong’s total area and 25% of developed land is reclaimed.

Two recent examples are informative. First was the creation of its airport. The old Hong Kong airport in Kowloon, Kai Tak, was built in 1925. Over the decades, the land around it was built up and made landing airplanes like threading a needle. It required the pilots to make a low-altitude turning maneuver before a rapid descent that “was so close to these buildings that passengers could spot television sets in the apartments.”

The New Airport

As this became unacceptable, Hong Kong built a new state-of-the-art airport. The end product, opened in 1998, was Hong Kong International, built on a large artificial island formed by flattening and leveling Chek Lap Kok and Lam Chau islands and reclaiming 3.62 miles2 (9.38 km2) of the new land. This project added nearly 1% to Hong Kong’s total surface. In addition, the old Kowloon land is now being redeveloped, which, when completed, will have 30,000 new homes, including 13,000 public housing units.

Lantau

My plan calls for a new 1760 acres. A new reclamation project under construction in Hong Kong entails 1700 hectares (1 hectare = 2.47 acres). So, my proposal is positively shrimpy compared to what’s happening in Hong Kong. The tremendous housing shortage has motivated the government to pursue it.

More Details about My Plan

Returning to New York, the city will be on the hook for billions of dollars for climate change mitigation, including seawalls, berms, and shoreline expansion. Additionally, as climate change damage continues to mount, the cost to homeowners will increase and will make the housing affordability problem that much worse.

The “opportunity cost” of doing half-baked measures will, in the end, be much more expensive than embracing large-scale efforts (I will leave an analysis of these opportunity costs for a future post). And it will be the poor and marginalized who will bear the greatest burden.

So why not try to be more economical and socially helpful simultaneously? If judicially executed, the plan could not only pay for itself but also provide money to help the city in other areas of climate change mitigation and for environmental improvements. Once built out, the land would then be on the real estate tax rolls, increasing the city’s revenues.

New Mannahatta

I called the land New Mannahatta to reference Manhattan’s historical name from the Native American Lenape people. We could use the parks and shorelines to install native plants and trees to encourage the return of native birds, butterflies, and other species. Central Park today is one of the largest human-made flyways on the Northeast coast, so why not add to that? We could engage in historic preservation by referencing the historical landscape, like how we have historically preserved about a quarter of Manhattan’s real estate.

I used the Upper West Side of Manhattan (Community District 107) as a model. The reason is that it’s a highly diverse neighborhood with many types of buildings that range from old-style tenements to brownstones to high-rise apartments and skyscrapers. It has a population of 180,000 and 129,000 housing units, and I estimate it contributes $1.4 billion in real estate tax revenue each year. Though it abuts Central Park, it has an array of parks within its borders, from the 134-acre Riverside Park to several neighborhood and vest-pocket parks. The hope is that we can use this opportunity to think about adding to Manhattan’s biodiversity.

The Economics of Plan

There is an economic logic to the plan when you crunch the numbers (more details are here). First is the cost of creating the new land. The fill would likely come from dredging. I also believe that creative recycling of other inert or excavated materials from real estate construction sites in the region can be added to the mix. Battery Park City was created from landfill from the excavation of the World Trade Center site, which was comprised of 18th– and 19th-century landfill when Manhattan’s western shoreline was expanded outward. In this sense, Battery Park City was created using recycled landfill.

The Cost

The fastest way to get a ballpark cost is to compare New Mannahatta to the Lantau plan in Hong Kong. The total cost of the 1700 hectares is expected to be about $81.1 billion (and which is cheaper than New York’s $119 billion proposed seawall), for about $19.3 million per acre. For my plan of 1760 acres, the total cost would be about $34 billion.

The Cost of Fill

Every year, the United States produces between 200 – 300 million cubic yards (153 – 229 million m3) of material from port dredging. In fact, between 2014 and 2018, ten U.S. ports alone generated over 300 million cubic yards (229 million m3) of dredged material to keep their ports functional.

Locally, in 2016 the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) completed a harbor deepening project (along with shoreline and wetland remediation). The shipping channels needed to be deepened to accommodate the larger, more efficient container ships. The PA removed 52 million cubic yards (32 million m3) of sediment, rock, and other material from the seafloor for $2.1 billion, for a cost of $40.38 per cubic yard (which by the way is incredibly high compared to the national average of $12, but it also includes disposal costs and shoreline remediation).[1]

I assume that New Mannahatta would need about 170 million cubic yards (130 million m3) of fill (roughly the average annual fill output from U.S. port dredging). Using the PANYNJ’s figure means the fill cost would be $7 billion. The rest would be used for infrastructure, creating the sheet pilings, and building new wetlands and beaches.

The Benefits

An estimated $34 billion might sound like a lot, but, literally and figuratively, it’s dirt cheap. The average real estate sale price of the Upper West Side in 2019 was $1,500 per square foot. Using a very conservative construction cost of $500 per square foot means a $1,000 “profit” per square foot that goes to the city for selling the real estate rights to developers.

Using the Upper West Side as a model, New Mannahatta, when fully built out, would have 240 million square feet of space, which could produce to the city a net revenue of $240 billion!!! Nearly an order of magnitude greater than the cost.

Let me repeat: the market value of the land would be worth $240 billion. The cost of producing it would be only $34 billion! That’s over $200 billion that could be used to make the Hudson River as clean and pure as it was in September 1609, when Henry Hudson first arrived. Even if the “profit” was “only” $500 per square foot, the net revenue to the city for building New Mannahatta would be $120 billion, still four times the costs.

Simply put, New Mannahatta makes sense because Manhattan sales prices are so much higher than the construction costs. New York has a chance to exploit and leverage this value for the greater good.

The Planning of New Mannahatta

For the sake of brevity, I will leave a more detailed treatment of an urban plan for the future, but a basic version was produced for the Times piece (my version given above). I kept the Grid Plan because I like it. It’s not great for some things, but it’s part of Manhattan’s DNA, so I think we should we keep it.

We could make blocks shorter and even add alleyways to keep trucks off the street. I added some bisectional roads à la Broadway, with one to be called New Mannahatta Boulevard. I added six internal parks, beaches and wetlands, and bike paths along the shorelines. Then there’s Governor’s Island (also a product of landfill) that would become the equivalent of Central Park. I included extensions of subway lines and places for ferries. The plan could even ban cars (but allow taxis and delivery trucks). Discussions of zoning and land use locations will be deferred for the future.

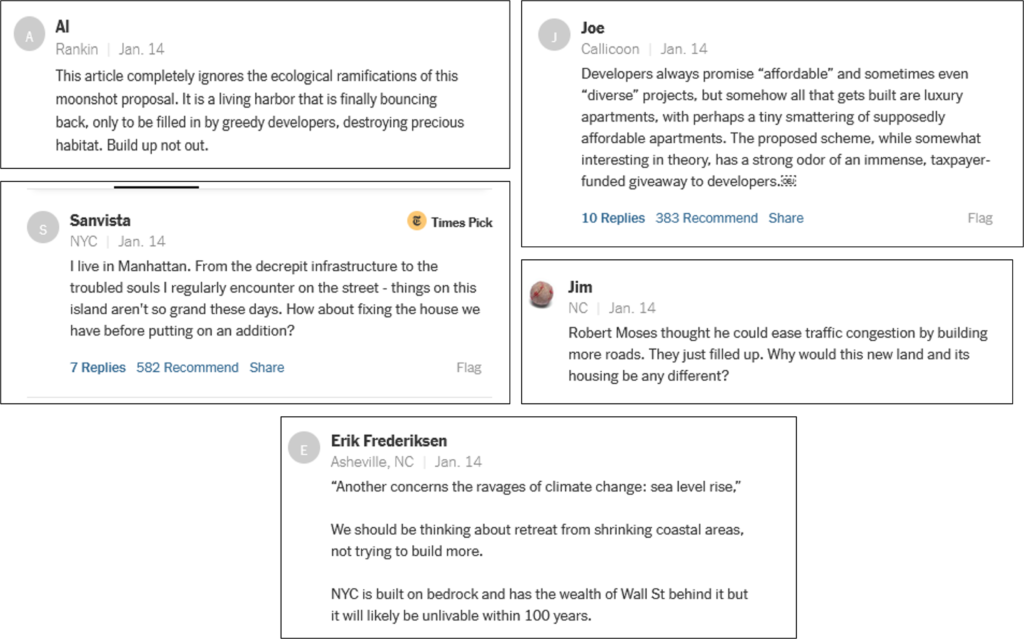

Addressing the Comments

Let me now turn to the laundry list of criticisms. They mostly fall under five major areas, which I summarize as: (1) it’s bad for the environment, (2) government can’t be trusted, (3) whataboutism, (4) it’s a giveaway to greedy developers, (5) there are cheaper alternatives, and (6) we should just abandon lower Manhattan to the sea. Let me address these in turn.

On the Environmental Concerns

Obviously, such a project will have environmental concerns. However, the key issue facing us is: how do we protect our society and the planet in the most efficient manner while minimizing the negative side effects?

Whether New Mannahatta gets built or not (which it most likely won’t), harbor dredging will continue apace, sea-level rise will continue apace, New York City flooding (and the sewage runoff into the Hudson it creates) will continue apace, housing affordability will continue to get worse, and so on. All the while, the cost of inaction will continue to escalate.

Nonetheless, to some ecologists and environmentalists, touching the water-based ecosystems, in and of itself, is taboo, regardless of the costs that leaving them alone may impose. True, much has been done since New York lost its manufacturing base to restore what were horribly polluted and degraded waterways and ecosystems. This is to be celebrated.

But if a person’s worldview is that you can’t touch the harbor because any economic activity that impacts it is “bad,” then there’s not much discussion we can have on this issue. However, we need to be clear that this is just another form of NIMBYism, which perpetuates and exacerbates our problems. And it drives policy makers to take short cuts that could wind up causing more environmental damages in the long run.

Regardless of the you-can’t-touch-the-estuary sentiment, seawalls will be built, shorelines will be extended, and harbors will be dredged (not to mention that rising ocean temperatures will likely cause environmental and ecosystem damage orders of magnitude greater than a well thought-out reclamation project). So, no matter how bad my plan seems to environmentalists, the question becomes: which is worse, the ad hoc approaches going on now (not to mention the damage caused by doing nothing) or a plan like mine? The answer is worthy of debate and discussion.

And, before creating the new land, careful scientific modeling can be used to reduce unintended consequences and produce strategies to help the estuary ecosystems. For example, the sheet pile walls for the fill can include curves, shelves, and other habitat features helpful for marine life, in addition to the new wetland habitats that would be produced.

Galaxy-Brained?

Willy Blackmore at Curbed.com called my idea “galaxy-brained.” Why? Because Robert Moses drained marshlands in Queens that flood to this day. I’m not proposing we drain anything; I’m proposing the opposite—that we create new wetlands that leisurely extend far out into the sea.

Blackmore is under the false impression that my proposal would somehow create a new floodplain. That’s absurd. The whole point is to create something that protects the current floodplain that is Lower Manhattan, which Superstorm Sandy swamped. Due to luck and high elevation, Battery Park City (BPC) was largely spared after Sandy. It motivated former Mayor Bloomberg to generate a proposal to recreate BPC on the East River. Mayor de Blasio’s plan was to extend parks into the East River as protection. My plan is similar but adds a new housing component.

After reading Blackmore’s post, one comes away with the impression that he needs to take the stand that “it can’t be done” because he, like many, is too cynical about government to solve our problems. His logic: Since Robert Moses wasn’t an environmentalist, it naturally follows that we should not consider my plan. Robert Moses was in power sixty years ago. I think we’ve learned a few things about shoreline remediation since then. Just ask the Dutch.

On “It’s A Giveaway to Greedy Developers”

Today, the average New Yorker blames gentrification and luxury condo construction on the greedy plutocrats who are taking over “their” city. To be sure, gentrification and condos for billionaires are important issues that warrant serious policy discussions.

But in my plan, the land is created by the city itself (or its designated authority). I will hold off on a more detailed discussion but, suffice it to say, the authority would have significant control over what gets built and for whom. Perhaps the easiest way to do this is to sell off long-term ground leases to developers with specific rules on how the units must be allocated to various income groups. In short, my plan allows for a variety of real estate types for all income levels.

On Whataboutism

A whole slew of commenters reproduced the tiresome trope of “whataboutism.” This logical fallacy says: we can’t do your plan because what about some other unsolved problem in the city completely unrelated to my plan? Sure, it’s easy to focus on the failures of the various government agencies. But nearly none of these directly address my plan on the merits or demerits.

One of the reasons I’ve offered this concept is because it would be absent many of the roadblocks that gum up the works (but, of course, there are a host of others). There would be virtually no residential displacement or disruption, and the new construction would take place far away from most people’s daily lives.

On We Can’t Trust Government

As for the “we can’t trust government” complaint, I think it’s sad that we’ve become so cynical. True, leaders are not angels, and they have made many mistakes in the past. But New York has become New York because of the “partnership” between the people and its government. The government constructed the subway system, the water system, and virtually all the infrastructure we have today.

That Robert Moses did things his way was arguably problematic. But we have turned Robert Moses into the Boogeyman of Bad Government. Highways, bridges, and tunnels would have been built nearly the same without Robert Moses. Did this one man destroy neighborhoods more than the thousands of other planners who ran their highways through Boston, Buffalo, or St. Louis? Debatable.

But here we are two-thirds of a century later since the Cross Bronx Expressway was plowed through the South Bronx, and we are using Robert Moses as a shield for NIMBYism. It’s time to say: “Yes, he made mistakes, but we can and have learned from them.” The truth is that only government can initiate some kinds of projects, and we need it now to help keep the city remain successful and affordable in the 21st century.

On There are Cheaper Options

Are there cheaper options? My answer is: indeterminate. In 2012, when Superstorm Sandy hit, the city got a loud wake-up call about climate change. When Irma recently hit, it showed the city had hit the snooze button and went back to bed. How many wake-up calls do we need before we take climate change seriously? The cost of inaction continues to mount. Half-baked measures plus the opportunity cost of these half-baked measures will likely be more expensive than creative proposals like mine.

Another frequent response was that New York should build more housing throughout the five boroughs. I couldn’t agree more. YIMBYism all the way! But the political hurdles to large-scale housing construction remain as strong as ever. Recently, Governor Hochul proposed legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and the NIMBYists fought back. Her plan has now been shelved.

Plus, just loosening the zoning and new construction rules may not fix the problem without policies related to reducing high construction and land acquisition costs and eliminating other hurdles preventing wide-scale housing construction (not to mention policies for improvements in the transportation infrastructure). I’m not holding my breath.

The point of my proposal is not that there are cheaper options (though this is debatable), it is that we should think creatively, efficiently, and holistically about solving our problems.

On Managed Retreat

One common trope is we should plan for the managed abandonment of lower Manhattan. I’ll just say that if you abandon lower Manhattan to the sea, you will put a stake in the heart of Gotham. Like it or not, Wall Street is the engine of an economy with 20 million people. If you force businesses to leave, it will start to tear apart the fabric of our society, and New York will slowly wither away (see: Detroit or Escape from New York).

What’s to Be Done?

To be honest, I don’t know if my proposal helps or harms the public discourse. We are so accustomed to automatically rejecting big ideas that my plan seems to have abetted the polarization. I’m not saying that my idea is the end all be all. But I do want it to help advance discussions about the best way forward for New York and our society more broadly.

To the knee-jerk naysayers, when a new idea is proposed in good faith, I ask that you don’t automatically reject it. Rather, think about ways to engage in meaningful dialogue that helps lead to solutions to our most pressing problems. Just because something “feels” like a bad idea, does not make it so. Perhaps you will keep this in mind the next time you post a critical comment on Twitter or the New York Times.

Sure, we may not get everything we want from new policies, but with reasoned discussion and debate, we can take control of our future and not succumb to self-defeating cynicism or become victims of our quest to preserve our own self-interest at the expense of the greater good.

—

[1] In addition, the century-old Jones Act prohibits U.S. ports from hiring international dredging companies. Today, the Dutch and Belgium have the world’s largest dredging machines which can (safely) dredge for pennies on the dollar as compared to U.S. companies. As a result, Americans pay a hidden tax on imported products because the cost of maintaining our ports is that much higher.